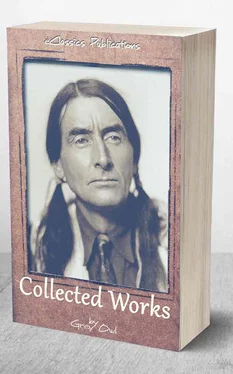

Grey Owl (Archibald Stansfeld Belaney) - The Collected Works of Grey Owl

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Grey Owl (Archibald Stansfeld Belaney) - The Collected Works of Grey Owl» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Collected Works of Grey Owl

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Collected Works of Grey Owl: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Collected Works of Grey Owl»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

"The Collected Works of Grey Owl"

Description:

"The Collected Works of Grey Owl" comprises the works of Grey Owl, or Wa-sha-quon-asin, the Indian name of English-born Archibald Stansfeld Belaney (September 18, 1888 – April 13, 1938), chosen by himself when he took on a First Nations identity as an adult. This collection consists of his three books «The Men of the Last Frontier», «Pilgrims of the Wild» and «The Adventures of Sajo and her Beaver People», all in one volume.

The Collected Works of Grey Owl — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Collected Works of Grey Owl», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Assuredly the hunt is no occupation for a pessimist, as he would most undoubtedly find a cloud to every silver lining.

There are many ways of killing moose, but most of them can be effected only at times of the year when it would be impossible to keep the meat, unless the party was large enough to use up the meat in a couple of days, or, as in the case of Indians, it could be properly smoked.

In the summer when they come down to water in the early morning and late evening, moose are easily approached with due care. They stand submerged to the belly, and dig up with the long protruding upper lip, the roots of waterlilies, which much resemble elongated pineapples. Whilst eyes and ears are thus out of commission the canoeman will paddle swiftly in against the wind, until with a mighty splurge the huge head is raised, the water spraying from the wide antlers, running off the "pans" in miniature cataracts, when all movement in the canoes ceases, and they drift noiselessly like idle leaves, controlled by the paddles operated under water. The moose lowers his head again, and the canoes creep up closer now, more cautiously, care being taken not to allow the animal a broadside view. On one of the occasions when he raises his head the moose is bound to become aware of the danger, but by then the hunters have arrived within rifle shot of the shore; so, allowed to provide his own transportation to dry land, he is killed before he enters the bush.

In the mating season moose may be called down from the hills by one skilled in the art, and threshing in the underbush with an old discarded moose-horn will sometimes arouse the pugnacity of a reluctant bull; but when he comes it is as well to be prepared to shoot fast and straight.

Many sportsmen become afflicted with a peculiar malady known as buck-fever when confronted suddenly by the game they have sought so assiduously. The mental strain of senses keyed to the highest pitch, coupled with the quivering expectation of a show-down at any moment, is such that this "fever" induces them either to pump the magazine empty without firing a shot or forget to use the sights, or become totally incapable of pressing the trigger. Gentlemen of that temperament had better by far let fallen moose-horns lie when in the woods during the early part of October. They certainly are lacking in the sang froid of a prominent business man I once guided on a hunt.

He was a man who liked a drink, and liked it at pretty regular intervals, when on his vacation. Included in the commissariat was a case of the best whiskey. Every morning when we started out a bottle was placed in the bow of the canoe and from it he gathered inspiration from time to time, becoming at moments completely intoxicated, as he averred, with the scenery. The agreement was that when the Scotch was gone the hunt was over, and, head or no, we were to return to town. It was not a good moose country. I had hunted all I knew how, and had raised nothing, and my professional reputation was at stake. The day of the last bottle arrived, and our game was still at large. As we started for the railroad I was in anything but a jubilant mood, when, on rounding a point, a large bull of fair spread stood facing us on the foreshore, at a distance of not over a hundred feet. I jammed my paddle into the sand-bar, effectually stopping the canoe, and almost whooped with joy; but my companion, who was pretty well lit by this time, gazed fixedly at the creature, now evidently making preparations to move off.

I urged an immediate shot. In response to my entreaties this human distillery seized his rifle and tried to line his sights. Failing, he tried again, and fumbled at the trigger, but the "scenery" was too strong for him. The animal, apparently fascinated by the performance, had paused, and was looking on. The man was about to make another attempt when he put the gun down, and raising his hand he addressed the moose.

"Wait a minute," said he.

Reaching down into the canoe he handed me over his shoulder not the rifle but the bottle, saying as he did so, "Let's have another drink first!"

After the first frosts bull moose are pugnaciously inclined towards all the world, and more than one man has been known to spend a night up a tree, whilst a moose ramped and raved at the foot of it till daylight. Whether these men were in any actual danger, or were scared stiff and afraid to take any chances, it is impossible to say, but I have always found that a hostile moose, if approached boldly down wind, so that he gets the man-scent, will move off, threateningly, but none the less finally. Although the person of a man may cause them to doubt their prowess, they will cheerfully attack horses and waggons, domestic bulls, and even railroad locomotives.

Bull moose are quite frequently found killed by trains at that time of the year, and they have been known to contest the right of way with an automobile, which had at last to be driven around them. A laden man seems to arouse their ire, as a government ranger, carrying a canoe across a portage once discovered.

It was his first trip over, and, no doubt attracted by the scratching sound caused by the canoe rubbing on brush as it was carried, this lord of the forest planted himself square in the middle of the portage, and refused to give the ranger the trail. The bush was too ragged to permit of a detour, so the harassed man, none too sure of what might occur, put down his canoe. The moose presently turned and walked up the trail slowly, and the man then picked up his canoe again, and followed. Gaining confidence, he touched his lordship on the rump with the prow of the canoe, to hasten progress; and then the fun commenced. The infuriated animal turned on him, this time with intent. He threw his canoe to the side, and ran at top speed down the portage, with the moose close behind. (It could be mentioned here, that those animals are at a distinct disadvantage on level going; had the ranger entered the bush, he would have been overtaken in twenty steps.)

At a steep cut-off he clutched a small tree, swung himself off the trail, and rolled down the declivity; the moose luckily, kept on going. After a while the ranger went back, inspected his canoe, which was intact, and put it out of sight, and it was as well that he did. He then returned to his belongings to find his friend standing guard over a torn and trampled pile of dunnage which he could in no way approach. He commenced to throw rocks at this white elephant, who, entering into the spirit of the game, rushed him up the trail again, he swinging off in the same place as before. This time he stayed there. The moose patrolled the portage all the hours of darkness, and the ranger spent the night without food or shelter.

A moose, should he definitely make up his mind to attack, could make short work of a man. They often kill one another, using their antlers for the purpose, but on lesser adversaries they use their front feet, rearing up and striking terrific blows. I once saw an old bull, supposedly feeble and an easy prey, driven out into shallow water by two wolves, where they attempted to hamstring him. He enticed them out into deeper water, and turning, literally tore one of them to pieces. Fear of wounding the moose prevented me from shooting the other, which escaped.

When enraged a bull moose is an awe-inspiring sight, with his flaring superstructure, rolling eyes, ears laid back, and top lip lifted in a kind of a snarl. Every hair on his back bristles up like a mane, and at such times he emits his challenging call—O-waugh! O-waugh!; a deep cavernous sound, with a wild, blood-stirring hint of savagery and power. This sound, like the howling of wolves, or the celebrated war-whoop when heard at a safe distance, or from a position of security, or perhaps in the latter case, at an exhibition, is not so very alarming. But, if alone and far from human habitation in some trackless waste, perhaps in the dark, with the certainty that you yourself are the object of the hue and cry, the effect on the nervous system is quite different, and is apt to cause a sudden rush of blood to the head, leaving the feet cold. The sounds, invested with that indescribable atavistic quality that only wild things can produce, under these conditions, are, to say the least, a little weakening.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Collected Works of Grey Owl»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Collected Works of Grey Owl» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Collected Works of Grey Owl» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.