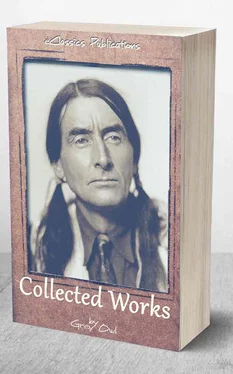

Grey Owl (Archibald Stansfeld Belaney) - The Collected Works of Grey Owl

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Grey Owl (Archibald Stansfeld Belaney) - The Collected Works of Grey Owl» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Collected Works of Grey Owl

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Collected Works of Grey Owl: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Collected Works of Grey Owl»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

"The Collected Works of Grey Owl"

Description:

"The Collected Works of Grey Owl" comprises the works of Grey Owl, or Wa-sha-quon-asin, the Indian name of English-born Archibald Stansfeld Belaney (September 18, 1888 – April 13, 1938), chosen by himself when he took on a First Nations identity as an adult. This collection consists of his three books «The Men of the Last Frontier», «Pilgrims of the Wild» and «The Adventures of Sajo and her Beaver People», all in one volume.

The Collected Works of Grey Owl — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Collected Works of Grey Owl», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All animals that live in the wilderness are provided with a set of protective habits which the skilled hunter, having knowledge of them, turns to his advantage. Beaver, when ashore, post a guard; not much advantage there, you think. But standing upright as he does in some prominent position, he draws attention, where the working party in the woods would have escaped notice. Both beaver and otter plunge into the water if alarmed or caught in a trap (in this case a stone is provided which keeps them there, to drown). Foxes rely on their great speed and run in full view, offering excellent rifle practice. Deer contrive to keep a tree or some brush between their line of flight and their enemy, and the experienced hunter will immediately run to the clump of foliage and shoot unseen from behind it.

Moose feed downwind, watch closely behind them but neglect to a certain extent the ground ahead. When about to rest they form a loop in their trail, and lie hidden beside it, where they can keep an eye on it, manoeuvring to get the wind from their late feeding ground. These things we know, and act accordingly. We decide on the animal we want, and make a series of fifty-yard loops, knowing better than to follow directly in the tracks, the end of each arc striking his trail, which is a most tortuous affair winding in and out as he selects his feed. We do this with due regard for the wind, all along his line of travel, touching it every so often, until we overshoot where we suppose the trail ought to be. This shows—provided our calculations are correct, our direction good, and if we are lucky—that our moose is somewhere within that curve. It has now become a ticklish proposition.

We must not strike his tracks near where he is lying down (he cannot be said to sleep), for this is the very trap he has laid for us. If we go too far on our loop we may get on the windward side (I think that is the term; I am no sailor). Pie for the moose again. Probably he is even now watching us. To know when we are approaching that position between our game and the tell-tale current of air is where that hazard comes in which makes moose-hunting one of the most fascinating sports.

All around you the forest is grey, brown and motionless. For hours past there has been visible no sign of life, nor apparently will there ever be. A dead, empty, silent world of wiry underbrush, dry leaves, and endless rows of trees. You stumble and on the instant the dun-coloured woods spring suddenly to life with a crash, as the slightly darker shadow you had mistaken for an upturned root takes on volition; and a monstrous black shape, with palmated horns stretched a man's length apart, hurtles through tangled thickets and over or through waist-high fallen timber, according to its resisting power. Almost prehistoric in appearance, weighing perhaps half a ton, with hanging black bell, massive forequarters, bristling mane, and flashing white flanks, this high-stepping pacer ascends the steep side of a knoll, and on the summit he stops, slowly swings the ponderous head, and deliberately, arrogantly looks you over. Swiftly he turns and is away, this time for good, stepping, not fast but with a tireless regularity, unchanging speed, and disregard for obstacles, that will carry him miles in the two hours that he will run.

And you suddenly realize that you have an undischarged rifle in your hands, and that your moose is now well on his way to Abitibi. And mixed with your disappointment, if you are a sportsman, is the alleviating thought that the noble creature still has his life and freedom, and that there are other days and other moose.

I know of no greater thrill than that, after two or three hours of careful stalking with all the chances against me, of sighting my game, alert, poised for that one move that means disappearance; and with this comes the sudden realization that in an infinitesimal period of time will come success or failure. The distance, and the probable position of a vital spot in relation to the parts that are visible, must be judged instantly, and simultaneously. The heavy breathing incidental to the exertion of moving noiselessly through a jungle of tangled undergrowth and among fallen timber must be controlled. And regardless of poor footing, whether balanced precariously on a tottering log or with bent back and twisted neck peering between upturned roots, that rifle must come swiftly forward and up. I pull—no, squeeze—the trigger, as certain earnest, uniformed souls informed me in the past, all in one sweeping motion; the wilderness awakes to the crash of the rifle, and the moose disappears. The report comes as a cataclysmic uproar after the abysmal silence, and aghast at the sacrilege, the startled blue-jays and whiskey-jacks screech, and chatter, and whistle. I go forward with leaps and bounds, pumping in another cartridge, as moose rarely succumb to the first shot. But I find I do not need the extra bullet. There is nothing there to shoot. An animal larger than a horse has disappeared without a trace, save some twisted leaves and a few tracks which look damnably healthy. There is no blood, but I follow for a mile, maybe, in the hopes of a paunch wound, until the trail becomes too involved to follow.

I have failed. Disaster, no less. And I feel pretty flat, and inefficient, and empty-bellied.

Worst of all, I must go back to camp, and explain the miss to a critical and unsympathetic listener, who is just as hungry as I am, and in no shape to listen to reason. Experiences of that kind exercise a very chastening effect on the self-esteem; also it takes very few of them to satisfy any man's gambling instinct.

A big bull racing through close timber with a set of antlers fifty or sixty inches across is a sight worth travelling far to see. He will swing his head from side to side in avoidance of limbs, duck and sway as gracefully as a trained charger with a master-hand at the bridle, seeming to know by instinct spaces between trees where he may pass with his armament.

It is by observing a series of spots of this description that a man may estimate the size of the bull he is after.

The tracks of bull and cow are distinguishable by the difference in shape of the hoofs; the bull being stub-toed forward, and the cow being narrow-footed fore and aft. Also the bull swings his front feet out and back into line when running; this is plain to be seen with snow on the ground of any depth; furthermore the cow feeds on small trees by passing around them, the bull by straddling them and breaking them down. Tracking on bare ground is the acme of the finesse of the still-hunt, especially in a dry country; and tracking in winter is not always as simple as would appear. More than a little skill is sometimes required to determine whether the animal that made the tracks was going or coming. This is carried to the point, where, with two feet of snow over month-old tracks, visible in the first place only as dimples, an expert may, by digging out the snow with his hands, ascertain which way the moose was going; yet to the uninitiated tracks an hour old present an unsolvable problem as to direction, as, if the snow be deep, the tracks fill in immediately and show only as a series of long narrow slots having each two ends identical in appearance. The secret is this, that the rear edge of the hind leg leaves a sharper, narrower impression in the back end of the slot than does the more rounded forward side. This can be felt out only with the bare hands; a ten-minute occupation of heroic achievement, on a windy day on a bleak hillside, in a temperature of twenty-five below zero. Nevertheless a very useful accomplishment, as in the months of deep snow a herd may be yarded up a mile from tracks made earlier in the season.

But should the herd have travelled back and forth in the same tracks, as they invariably do, we have confusion again. In that case they must be followed either way to a considerable hill; here, if going downhill they separate, taking generous strides, or if uphill, short ones. Loose snow is thrown forward and out from the slots, and is an unfailing guide if visible, but an hour's sharp wind will eradicate that indication save to the trained eye.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Collected Works of Grey Owl»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Collected Works of Grey Owl» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Collected Works of Grey Owl» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.