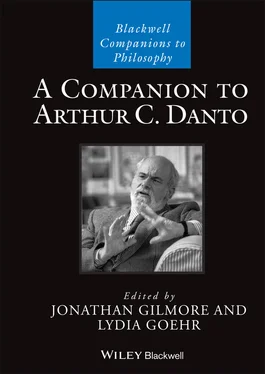

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Companion

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But could ideas by themselves wreak such havoc? For me, puncturing the boundary of what Arthur termed the “post-historical” era in art was a sociological event as much as a philosophical one. It had to do with the shattering of the tradition-bound confines of the art world, which for all sorts of complicated reasons had been trapped, like a fly frozen in amber, in a latticework of premodern sociological relations. The 1960s seem quaint in our eyes now, but this was the time when the art world was beginning to turn into a much larger and culturally and economically integrated, national and international entity. Growth and commercialism went hand in hand. The shared discourse that had hitherto bonded the small, informal community of art-world denizens, and provided a matrix of common understandings and a relatively clear sense of historical direction, was starting to evaporate.

Big, complex, market-driven systems are pluralistic by nature. They splinter into niches and sub-niches – so many lagoons in the wider ocean. Think of a dinner table. Eight people can easily maintain a shared conversation. Once you have a dozen or more, they pair off and cluster. Different conversations sprout up at each end of the table. Something similar was going on in the art world. Art galleries exacerbated this fracturing. The gallery system responded to growth by multiplying in numbers, rather than by scaling in size. Big fish didn’t eat the little fish. The little fish multiplied. By the 1980s, what had been a handful of Manhattan galleries had given way to hundreds, each one a microcosm of its own. Countless more were taking part in a burgeoning global art conversation. This metastatic complexity, and the resulting discursive opacity, was an evolving sociological condition that was catalytic to the onset of aesthetic pluralism. Or so I argued.

In short, for me, the story of the art world was, above all, a parable of modernization: of the agony and ecstasy, the losses and gains, of what it means to grow into a mature, highly organized, transactional industry. I think Arthur saw this as an interesting subplot on the margins of his deeper and wider macro-narrative. We spent many hours as well talking about the art world’s micro-dynamics. Here, too, Arthur was inclined to leave the details to others. He was famously reticent about being linked to an institutional theory of art. Nonetheless, as a former artist, he took a keen interest in the day-to-day functioning of galleries and the art market. Galleries, after all, did the work of filtering the universe of artists and artworks, elevating some to wider attention and, if all went well, inscribing the lucky few into the permanent art-historical record. Arthur and I had fun unpacking just how this accreditation of cultural legitimacy happened – how certain galleries and gallerists achieved the authority to do this work, and how, through each individual exhibition, and the unfolding chain of gallery exhibitions and sales over time, certain artists and objects were woven into the enduring narrative of art.

Crossing over into the sociological realm led to another adventure, involving a pair of Russian émigré artists, Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid. The two had made boundary crossings central to their lives and to their art collaboration. As proponents of a kind of Russian pop art, they thumbed their noses at the Soviet state, which they had left behind, continuing their gadfly projects in America, where they found a measure of success. Komar and Melamid convinced Arthur to advise them on their ongoing undertaking, whereby populations of entire countries would be polled about their tastes in art. Did you know that blue is the favorite color of all but one country? Komar and Melamid painted “most wanted” and “least wanted” images based on the findings of each survey. They decided that after having polled lay populations, it was time to study the experts. So they sent questionnaires to the membership of the American Society for Aesthetics. I was asked to organize the survey and write the report.

In the winter of 1996, Arthur and I went to Montreal for the society’s annual conference. We presented our findings in a “town meeting” discussion. The session was memorialized in a conference report, which, based on my analysis of the survey data, pointed out that “apparently the society waffled about a number of questions, refusing to commit itself unconditionally and non-contextually to questions of taste.” 2Accordingly, on my urging, the artists had summarized the survey conclusions pictorially around the theme of equivocation. They produced a diptych composed of a larger and a smaller image, reflecting the aestheticians’ lack of commitment on the matter of painting size. “When the ‘most wanted’ and ‘least wanted’ paintings were arranged by the artists with one directly above the other and a thin metal band separating them,” the society’s publication recorded, “they exactly approximated the shape of an ordinary refrigerator.” It was just the sort of intellectual merriment that Arthur loved. It required a sense of humor and a willingness to go where others in his position might not feel appropriate going.

3 Today’s Art World

My dissertation research involved interviewing the artists and employees of three leading New York galleries. Being connected to this process allowed Arthur to indulge in his journalistic fascination with the art world. He was far from a disengaged observer of the scene. He loved going out. He loved parties and enjoyed eating in restaurants. He relished fraternizing with artists, collectors, curators, and gallerists. Those who knew him were aware that philosophy and his late-blooming career as a critic, in the end, allowed him to enter the innermost sanctum of the art world in a way that his own abandoned project as an artist did not. The subway ride from Broadway and 116th Street to downtown represented another boundary crossed, the one between Arthur’s day job in the ivory tower and the raucous art scene where his soul, I believe, more comfortably resided. His capacity for moving effortlessly between those disparate realms set him apart from many of his peers, who were either hopelessly incapable of grasping the codes and fashions of the art world, or were no less hopelessly imprisoned by them.

Art criticism was for Arthur largely a way of practicing philosophy by other means, but it grew into something more. He was keenly aware that his ideas had an impact. He took credit for giving expression to a predicament in which art found itself in the latter part of the twentieth century. It was a situation he had helped to raise to a certain level of consciousness. But having helped usher in an anything-goes pluralism, he also provided an antidote to it: his criticism. Art criticism was a means of demonstrating how to cope with the bewildering, even paralyzing freedom of a contemporary art no longer pinned down by conventions of form, taste, or subject. It was a way of keeping up an appetite in a supermarket of art where the aisles were stocked with every conceivable type of expression. It was easy to lose one’s hunger for the new in the midst of this cornucopia. The solution was keen attention to what the eye can see, coupled with a Zen Buddhist-like big-hearted generosity in framing a response to an encounter with a work of art.

In the fall of 1994, Arthur and I took a walk around the downtown galleries. We stopped in on an exhibition by the photographer Andres Serrano. If memory serves correctly, it was his Budapest exhibition, at the Paula Cooper Gallery. The topic was of particular interest to me, because some of the images were apparently taken in my Budapest apartment, which I had rented to an American friend, who had allowed Serrano to use it as a set, or so I was told. Walking through the exhibition with Arthur provided a lifelong lesson in how to look at art. Serrano was no longer the wunderkind celebrated and scorned for his 1987 Piss Christ . In my mind, his recent depictions of nudes and corpses were cheap shots. As I walked through the show, I complained to Arthur that I found the work exploitative. Arthur had a roundly different response. After taking a long look, stopping deliberately in front of each picture, he launched into an exegesis on medieval pictorial conventions, pointing out analogies in Serrano’s work to which I had been utterly blind. We might as well have been viewing two different exhibitions. What Arthur brought to the act of seeing art was a full awareness, a willingness to engage the sum of his empathy and erudition. He later confided that he would almost never write about art he didn’t like. Panning art was cruel and a waste of time.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.