A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Companion

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was sometimes said of Danto, with admiration or consternation, that he saw the world as it should and could be, not as it was. It would imply too volunteerist a perspective to say that he chose to adopt this perspective, but he certainly recognized having it, blaming it on being been born on January 1st, in which, he said, “Each year opens on a new page, for me as well as for the world.” In truth, Danto’s way of seeing the world was as essential a feature of his identity as any other might be. He suffered, and he suffered with you, and his optimism was not held blithely. Instead, it represented in some ways a moral stand, one no doubt a source of frustration to those who wanted him to share in their cynicism, however, warranted that might be in academic locales. For me, and I’m sure for many others around him, his attitude, his exemplary being, was a source of strength: a goad to think, when possible, beyond what was currently a source of pain; and not to curse the world even if one was right to curse one small part of it. And his cosmopolitanism and earthiness, and his profundity as a philosopher, made that stance credible, when it might have seemed an artificial conceit in others. Although he engaged in the ruthless disputation required of professional philosophers, where expressing too much agreement with another’s argument is a form of discourtesy, Danto was contemptuous of the academic déformation professionnelle of taking pleasure in snide and cavalier criticism. False sophistications and too-clever-by-half arguments made him impatient. Yet he delighted in wit, even at his expense, as when he was told by a graduate student of a somewhat deconstructive bent that the indefinite article in the subtitle of his book – “a philosophy of art” – appeared to betray a false modesty.

Danto didn’t believe in an afterlife and took some comfort in knowing, he said, that the end really was the end. But, of course, one keeps in one’s mind an image of those we lose. When turning older, he embraced the observation that he and Socrates shared a physiognomy, and he showed me from time to time pictures that friends sent him of busts of the ancient philosopher that made the comparison highly credible. But I continue to think of him through another set of images, those painted several years ago by his wife, the artist Barbara Westman. In these, she has represented the two of them as Adam and Eve in the Garden. And there he is, with grey beard and bald pate, dancing, kissing, and otherwise cavorting with his partner, while beasts of the kingdom somewhat quizzically look on. Danto beamed with pleasure when showing these images to visitors, a pleasure that declared the great happiness he found in his life with Barbara, and the happiness, I think, of the figure by which he is represented in that Eden.

Figure 5Reproduced with permission of Lydia Goehr.

Acknowledgment

These essays were originally published in the American Society for Aesthetics Newsletter 33.3, which is available on the ASA website: https://aesthetics-online.org. Photography by Lydia Goehr.

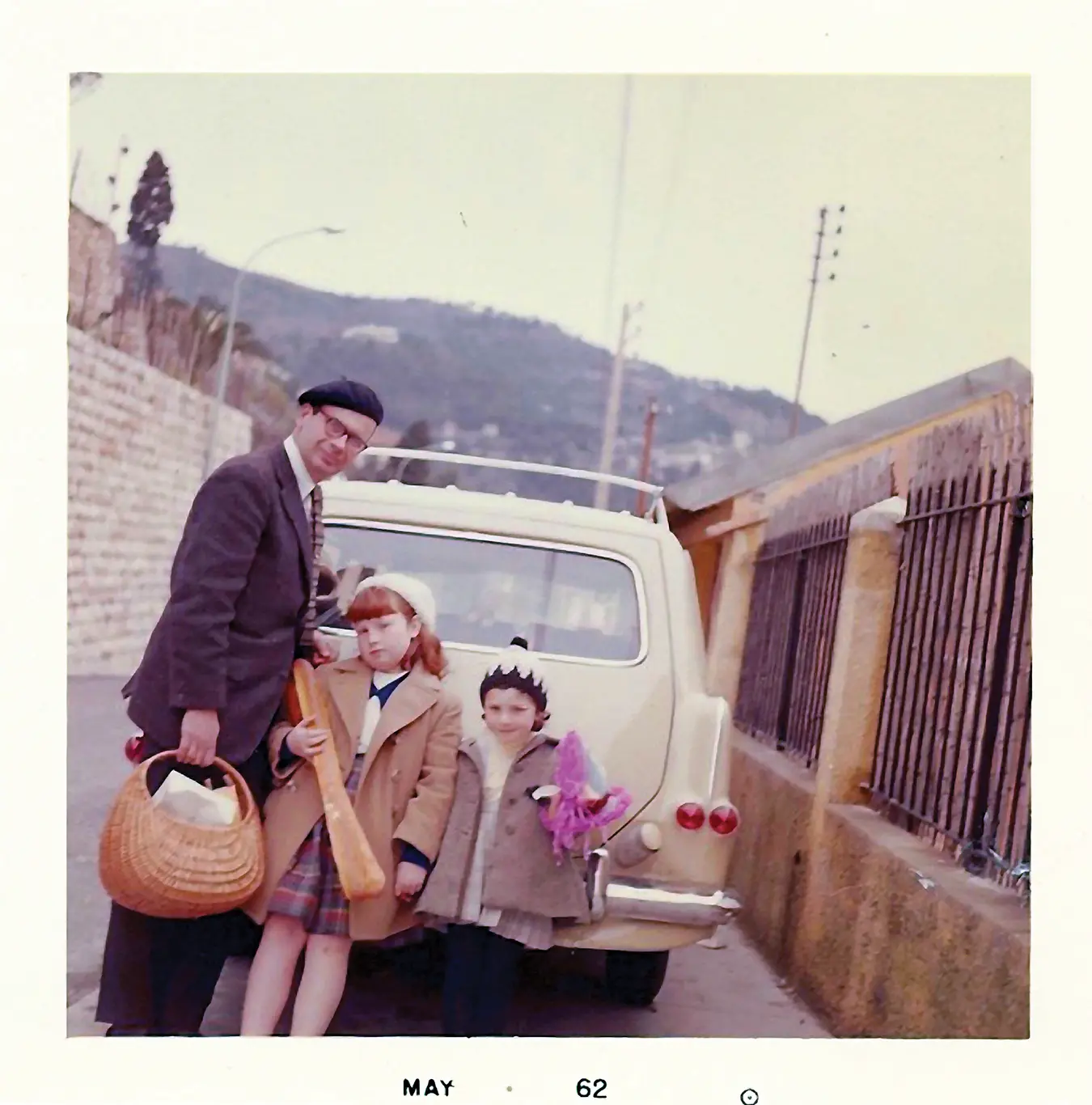

1 Roquebrune, 1962

GINGER DANTO

My sister and I were little. We rode in the scratchy backseat of a mustard-colored Citroën sedan. No seatbelts. It was 1962, the south of France. The countryside was raw, the villages small and closed, the only sign of life smoke coming from the chimneys. Grandmothers were home cooking. Men were in the fields.

For my father’s first sabbatical year from Columbia University, my parents settled in the tiny, sloping village of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, probably because of the house, that had not just a kitchen with a terrace and a view of the sea, but a spare upper room where my father could write. It was the Côte d’Azur before it was the Côte d’Azur. Life was slow, simple. Celebrities were still only interested in the yachting playgrounds of Monaco and Monte Carlo.

My father was by then keen on philosophy: it was his subject as an academic, the analytical his trade as a professor. But art and art making still held sway from his formative career as an artist of moderate success in our hometown of New York City. That was where he made woodcuts, in the apartment where we grew up, with the dusty perfume of woodchips everywhere littering the floor, splashes of ink on the wood panels and sheets of luminous rice paper for printing, rolled and ready for use.

He didn’t have any of this when we traveled, however, much less a studio. Just a blue black Olivetti and a battered briefcase, the same one he carried around on campus. But among the books and manuscripts was invariably a sketchbook, or a portfolio of Sennelier paper, with somewhere a bottle of ink, a pen, and a set of watercolors.

Reading my father describe his early life as an artist, particularly his famous discussion of giving it up, I was surprised to see him say categorically that he never used color. Or that color didn’t interest him. That his medium was all prints, all black and white.

Certainly, the woodcuts were his signature and what afforded a certain income, beyond his professor’s salary, that he admitted “meant a lot.” But when we traveled as a young family as we did summers as well as sabbatical years, to France and Italy and parts of New England, my father went beyond drafting mere sketches, in pencil or pen and ink, to filling these with color—dots and dashes of light, luminous pastel—pale washes of color reminiscent of the very Cezannes that in their ultimate perfection eventually closed the door for him, he said, to ever making art again.

I remember the reflex he had when we would stop somewhere for lunch, of taking out his sketchpad, and while my mother unpacked a picnic of salads in little waxed paper boxes from the local épicerie, with the requisite baguette and log of sweet butter, he would sit and make a study of whatever scenery we found ourselves in. Or, if that proved uninspiring, he would ask one of us to pose, and in my infinite ennui as a child more interested in playing with my stuffed animals than sitting perfectly still, I suffered there on some rock or bench as my father sketched and squinted and I must say—smiled—until we were both released by the communal call to eat.

He worked very fast; it was my sister Elizabeth who remembered this, who at age ten or eleven accompanied him around Rome in the afternoons to this or that architectural site for what my father called “analytical sight-seeing.” As the resulting architectural pen and ink effigies were not leisurely studies but rather attempts to interpret information drawn from books by Janson and Rudolf Wittkower, the Columbia art historian who became a close friend, and whose “Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism,” my father wrote in his 2013 intellectual autobiography, “had the greatest philosophical influence on me of anything I had read about art.”

In this exhibit there are other edifices, notably Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane, where the artist was interested in the convex and the concave. “The idea that it was something invisible that gave structure to the visual turned me around completely in my way of looking at art,” my father wrote later on, recalling these epiphanies, that for him had echoes in Oriental philosophy, for example, and that occurred on these repeated Roman excursions in the footsteps of the Baroque.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.