I am much obliged to Megan Wolf who quite literally runs the institute, and am infinitely in debt to Nicole Topich, the most resourceful librarian of the Oskar Diethelm Library, who never failed to provide me with the necessary sources, no matter how obscure they were.

Last but not least, I would like to pay special thanks to Lucy Bergeret. First as my teaching assistant at the Humanities Center at Johns Hopkins University and, more recently, as my research assistant and a wise editor, Lucy’s superb input and wise advice, especially during the last few months of finalizing this book, were indispensable. A philosopher, an intellectual historian, and a scholar of comparative literature, Lucy has made this book a whole lot better than it would have been otherwise.

Thanks to the editorial staff at Polity Press, Ellen MacDonald-Kramer and Stephanie Homer, for shepherding me through this project, and especially to the series editor, Pascal Porcheron, for his undiminished belief in this work, his patience, and his wise counsel. I also want to thank the two anonymous readers of the Polity Press for their thoughtful and rigorous feedback on this manuscript. Their invaluable input helped clarify my argument and improved this book.

The last year of working on this book took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and the barely veiled assault on democracy in the United States, where I was located and found a second home. I am thankful to my family and friends, whose steady stream of expressed interest, care, and concern, and whose blessed sense of humor, contributed to the finalization of this project, keeping me sane along the way.

No one can measure the embracing presence in my life of my mother, Aliza Ophir, my brothers Ori and Arnon Ophir, and my long-time dear friends Sigal Avin, Shiri Broza, Aya Seker Einbinder, Alon Hager, Maya Levi, Michal Kaplan Rokman, Efrat Shamgar, Daphna Spigelman, Gil Talmi, Antal Tzur, and Ruth Weinberg. I feel privileged to have found new neighbors and friends in a welcoming community, and especially the McCollum-Garlins, the Schindler-Schuls, the Kramers, and the Nicosias, all of whom were enormously supportive at the final stages of writing this book.

My most heartfelt gratitude goes to the loves of my life, Britt and Alma, who graciously awaited the completion of this manuscript, and were unbelievably tolerant. By the time its last pages were written and proofread, they had grown taller, more beautiful, and even more talented. As always, they kept their charming and funny traits intact! I cannot wait to spend much needed time with you again. You are my miracles, and thank you for insisting on getting us Tulip, our pandemic puppy, who quite literally pushed me off my desk chair when it was high time to do so, taking me on daily walks along the bay and in the city.

This book is dedicated to Hent, my toughest reader and my partner in all things worth living for. If it were not for you , it would not have been at all.

Introduction: The Ends of a Diagnosis

“It’s a word, that’s all, a word that covers a large, loose category,” the psychiatrist explained, “it’s like saying ‘tree.’ There are all kinds, firs, elms, pines. So there are many kinds and degrees of schizophrenia.” (Louise Wilson, This Stranger, My Son , 1968) 1

When Tony was discharged from the hospital, his father, Jack Wilson (a surgeon by profession), had enough of the conflicting reports and wanted a “real diagnosis.” Dr. Brewster, the psychiatrist, who thought Tony’s parents surely realized he was “very sick,” concluded: “schizophrenia, if you want to label it. The boy is a paranoid schizophrenic.” Shocked by the doctor’s response, Tony’s mother, Louise, echoed the expert’s words: “ schizophrenia, if you want a label ,” thinking all the while about her son’s dark blue eyes, his beautiful, rare smile, but also about the “ugly contortions of his rage,” his terror and fear.

What was this strange phenomenon of Tony’s illness? Was it “a thing,” of a natural, biological, or ontological, kind? Was it a phenomenon to be understood as a matter of degree, as part of a broader spectrum, a scale or continuum? The psychiatrist’s choice to describe it as a “loose category” (just a “word”) certainly had not made things easier to decide. Neither had his comparison with the natural kind of a “tree,” or his evoking the “many kinds and degrees” of schizophrenia. Did the name “schizophrenia” or “paranoid schizophrenia” offer an adequate characterization in and of itself, a genuine definition, of the ailment Tony appeared to be suffering from? Or did it merely introduce another label (if one “wanted” one), adding on to the numerous, equally apt or vague, preexisting ones? In other words, what is – and what was – “schizophrenia,” precisely?

While this book is intended for a broader interested audience, it makes informative excursions here and there into topics that may speak to specialists and therapists alike. It will ask a few simple questions, to shed light on the different ways in which Tony and his family’s situation might be understood: can the term schizophrenia be considered as a natural kind in its own right, whose members are constituted by a similar set of biological mechanisms, and can its application to a particular case be determined with certainty? Can paranoid schizophrenia, for instance, be considered as a subspecies of a kind that shares a similar natural causal structure and, hence, as a biological classification rank of schizophrenia (just as an “elm” or a “pine” are types of trees)? Or does schizophrenia have many kinds and (unlike trees), many degrees, as Dr. Brewster seems to suggest? Is it a category (in the same way that “tree” is one), albeit composed of distinct kinds and varying degrees? Was Dr. Brewster diagnosing a natural disease (“schizophrenia”) or was he diagnosing Tony as a type of person (a “paranoid schizophrenic”), taking the latter as part of a wider spectrum of mental deviancy that differs only in degree (rather than in kind) from psychological “normalcy,” broadly construed? Or should we consider schizophrenia (as did some American psychiatrists in the 1960s) as no more than a “word,” that covers a “large, loose, category”?

To answer these questions, we will abstain from trying to draw out some timeless essence of schizophrenia, an implausible enterprise if ever there was one. Rather, we will limit ourselves to examining its genesis as a medical and psychiatric diagnosis, and describe and evaluate its uses in the clinical and therapeutic professions over time. In so doing, we will try to understand not only its history and present characteristics, but also what kind of future this diagnosis and the proposed treatment for it might still hold in store. In other words, we will aim to see what picture emerges once one no longer takes the diagnosis of schizophrenia to be that of a stable identity per se, but also one of perspective. At times, the diagnosis will be, and perhaps needs to be, placed on a continuum or a spectrum with the normal and, at other times, be seen and appreciated as if it were a fixed category of illness, a natural kind, of sorts.

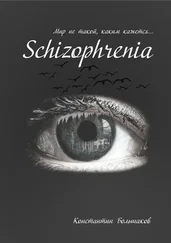

This dual vision of one and the same phenomenon recalls the picture shown in figure 1, which Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher and historian of science, following Ludwig Wittgenstein, borrowed from the psychologist Joseph Jastrow, to demonstrate “the structure of scientific revolutions.” According to Kuhn, even when nothing in the environment has changed, the shift of attention of the scientific community transforms its perception of the phenomenon all at once, and “[w]hat were ducks in the scientist’s world before the revolution are rabbits afterwards.” 2The relationship between the two distinct paradigms of diagnosing schizophrenia may be just that, with the important difference that in the case of the latter it is increasingly evident that the two pictures somehow continue to alternate – that is, flip back and forth – throughout history.

Читать дальше