Partner at Bain Capital Ventures, Matt Harris breaks down the evolution of fintech into two components. The first focus is digitization. As Matt puts it, “If you go back 20 years, that's what the world needed. All financial service companies—banks, insurance, and wealth companies—are extremely analog. This is true from account opening through to servicing, underwriting, everything they did required in-presence work and tons of paper.” The early fintech companies answered this need. Companies like OnDeck, Lending Club, Square, the first neobanks like Moven and Simple. These early fintechs took well-understood and utilized products and digitized them. While this sounds simple, it is actually quite hard to execute well and the companies that did got big rewards. Many of the companies that were created and grew from the first version of fintech Matt described have gone on to become public companies with valuations in the billions or be acquired for hundreds of millions. There was real traction here, but Matt questions how innovative it was: “It really wasn't changing much about those products other than the user experience. It improved the lives and experiences of consumers and businesses but it wasn't actually fundamentally disruptive.”

So what does disruption in financial services look like? That is wave two, according to Matt. In wave two.

Once you digitize these products, you can embed them in software that consumers and businesses are already using all day. By embedding it, you can make them less expensive and you can inform them with the data that these software products contain. Embedding is not an incremental step forward from that analog to digital phase. It's actually transformative, and we've got room to go here.

A prime example of this in action is through fintech companies like AvidXchange or Bill.com. Their account payable software allows companies to save an incredible amount of time by automating the process, which is a vast improvement from using a lock box operator. As AvidXchange shares on its website, 10 the goal of the software is to “give teams the flexibility, security, and efficiency to approve invoices and make payments anytime, anywhere.”

The companies that utilize the data and resources around them to truly understand their customers are the best positioned to offer them financial solutions, which is another point in favor of embedded finance.

With the advent of fintech, banks slowly came to understand they were not only competing with other banks, but with tech-forward upstarts. Soon they would realize there were even more competitors in the market than they dreamed of. If we look at the advantages of technology, data, and a deep understanding of your customer, it is reasonable to think that, at least in part, nearly every company in the world has the potential to be a financial services company!

The new fintech companies focused their efforts on one product, or even one aspect of one product, and devoted their skills and expertise in order to execute it perfectly. With regard to lending in particular, bankers have long argued that Silicon Valley technologists lack the expertise to build the right product and manage the risk, but increasingly these functions are automated and software does the work. As financial services become more digital, technology companies feel more at home with these products.

The first question investors ask entrepreneurs is often, “What problem are you solving?” Fintechs were developed to take on specific problems, such as consolidating credit card debt for which banks no longer delivered solutions. For the generation that came of age in the wake of the financial crisis, there was a feeling that banks were simple utilities rather than companies looking to delight their customers and deliver elegant solutions. And we will see later in the book on why this utility angle, called “banking-as-a-service,” is an opportunity banks cannot miss, given the opportunity it represents for them in the era of embedded finance.

Banks foreclosing on the homes of buyers who were encouraged to take out a loan they couldn't afford reinforced this perception. Fintech companies capitalized on this in the early days, emphasizing that banks make money when customers suffer, when they can't pay off their credit card balance every month, or when they overdraft their account. Customers wondered with some justification if their bank was even on their side. This misalignment of interest between banks and their customers led to further alienation and made consumers more likely to seek out nonbank solutions.

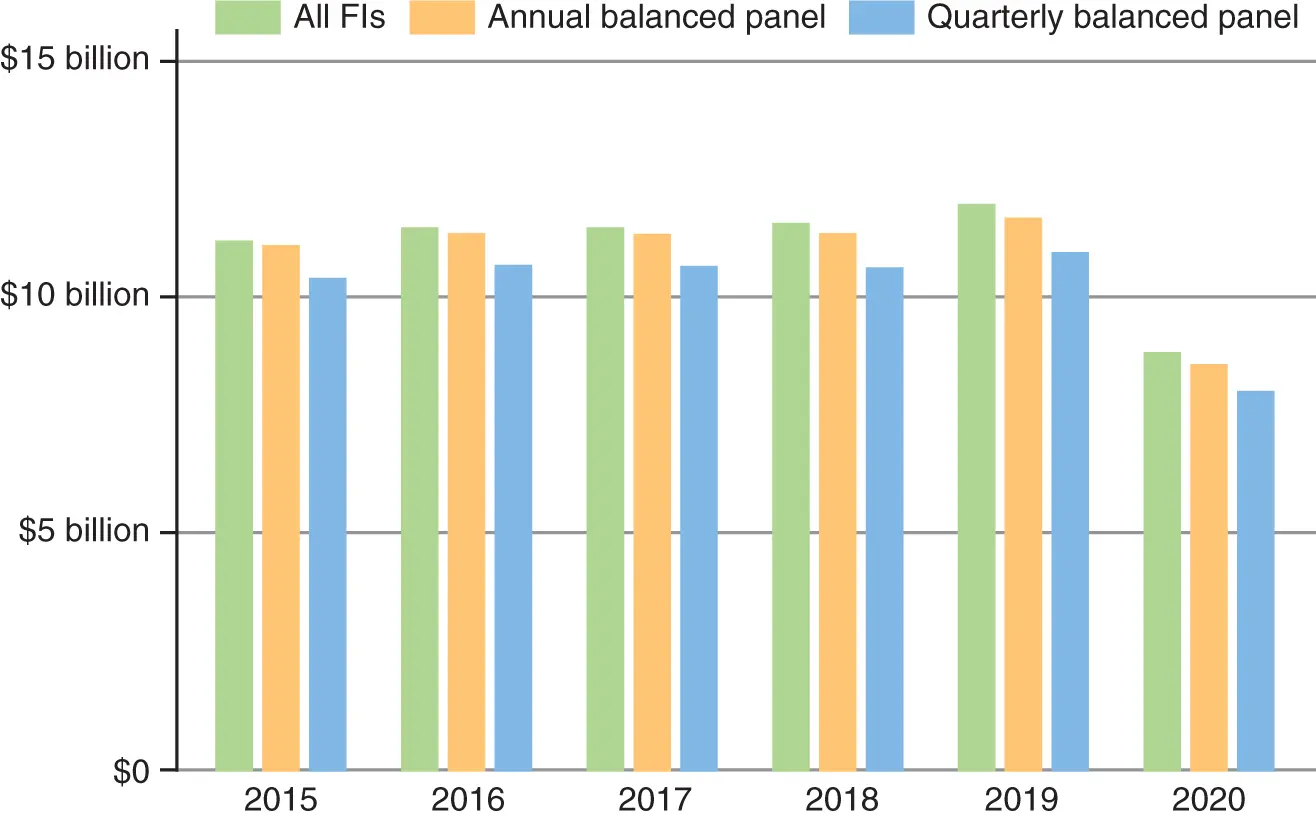

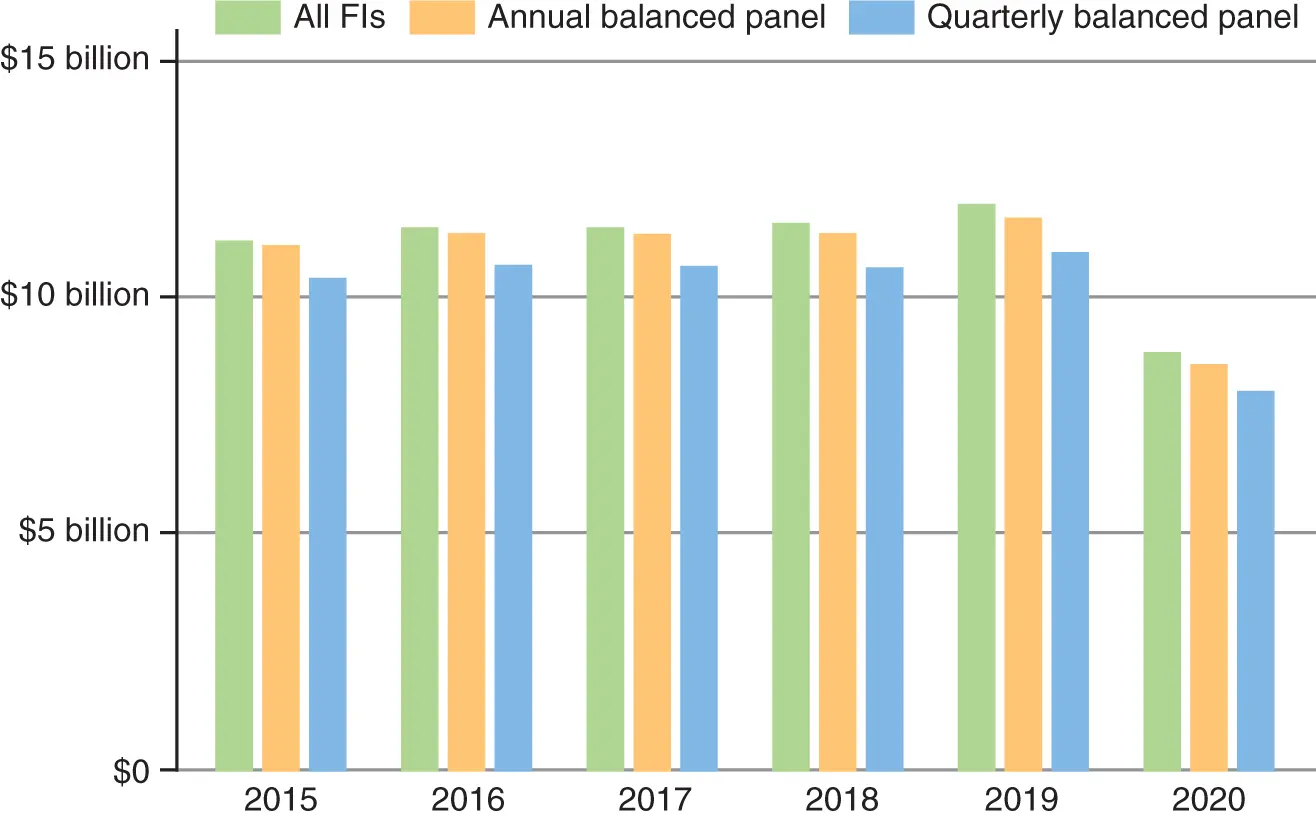

This misalignment is not just theory. In 2020, US banks in aggregate collected about $8.8 billion in overdraft fees. This is an unusually low figure from a very unusual year ( Figure 2.1). The previous year, banks collected over $12 billion. JP Morgan Chase and Bank of America collect the most in absolute dollars, but overdraft contributes a smaller percentage of their bottom line than regional and midsize institutions.

Figure 2.1 Aggregate overdraft/NSF (non-sufficient funds) fee revenues by year in the call reports.

Source: CFPB report Dec. 2021 / Consumer Financial Protection Bureau / Public domain

THE ENTRANCE OF THE NEOBANKS

The unbundling of the bank continued throughout the 2010s, with virtually every banking function being reproduced and in most cases improved upon by fintech startups. Even backend functions that are remote from the customer experience were re-created by fintech startups.

This continued innovation led to the creation of a new category of fintech called neobanks—digital-only banks built from the ground up. Neobanks aimed to take over the customer experience entirely from banks, and offered a broad suite of products for their users, though this range of products was generally narrower than that offered by banks.

The first neobanks launched in the early days of fintech: Simple, co-founded by Shamir Karkal and Josh Reich, and Moven, founded by Brett King, are two well-known retail examples on the US side. Both saw great initial traction, and Simple was known for having the second highest NPS (net promoter score) across all of financial services behind USAA, which serves members of the armed forces and their families. 11

Founded: 2009

Market cap: n/a

Number of employees: n/a

Founded by Shamir Karkal and Josh Reich, Simple's mission was to deliver clear and transparent digital banking to a population disillusioned by the financial crisis of 2008–2009. Simple was the paradigm of the neobank in the US.

Simple, which operated completely online, pioneered the Safe to Spend feature and was legendary for its hands-on customer service. The service was bought by the global bank BBVA for $117 million in 2014, and shut down in 2021.

Shamir Karkal remembers the early days when the idea for Simple emerged:

I was chatting with Josh who was (and still is) a good friend. And he sent me this email saying, “Let's start a retail bank.” I remember this was 2009, and we spent a lot of time chatting about the financial crisis and everything that had happened from ’07 to ’09. It wasn't completely out of the blue for him to talk about entrepreneurial ideas with me, but, starting a retail bank was like, what was out there? He laid out this vision of how customers hated existing banks. The whole financial model of banks was built around trying to sell more products to customers and charge them more fees. What customers wanted had not been articulated, but what customers wanted was financial wellness, and they wanted to have access to their money, and really to live a better life. There was such a deep disconnect between what banks were selling and what customers were asking for. And Josh's idea was, “Hey, let's just build a simple, easy-to-use customer-friendly bank that held your money, helped you pay your bills, gave you loans when you needed them, and then got out of your way and let you live your life.” And it was just such a compelling idea. I read that email and I was, like, “Oh man, we should do this now.” Facebook and Twitter were already beginning to take off. And yet most banks did not even have a mobile app at that point.

Читать дальше