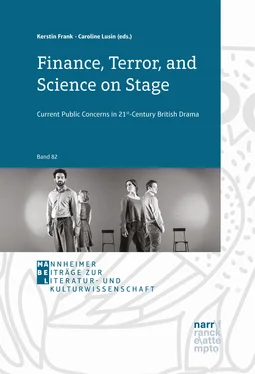

Kerstin Frank, Caroline Lusin (eds.)

Finance, Terror, and Science on Stage

Current Public Concerns in 21 st-Century British Drama

Narr Francke Attempto Verlag Tübingen

[bad img format]

Umschlagabbildung: Joan Marcus. Photo of the production of Nick Payne’s Incognito at the Manhattan Theatre Club, New York, 2016 (directed by Doug Hughes, scenic design by Scott Pask)

Signet: Motiv vom Hals der Qinochoe des ‚Mannheimer Malers‘ (Reissmuseum Mannheim, Mitte des 5. Jh. v. Chr.)

© 2017 • Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH + Co. KG

Dischingerweg 5 • D-72070 Tübingen

www.francke.de• info@francke.de

Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen.

E-Book-Produktion: pagina GmbH, Tübingen

ePub-ISBN 978-3-8233-0019-9

No collection of essays is a solitary project, and therefore we would like at this point to express our gratitude to all those involved. First of all, we would like to thank our contributors, without whom this volume simply would not exist. Thank you for your excellent collaboration! Secondly, we are very grateful to the publishing team of Gunter Narr Verlag, particularly Kathrin Heyng and Vanessa Weihgold, for their unflinching support and patience. And, last but not least, we owe a great debt to Annika Gonnermann and Lisa Schwander, who assisted us in the editing process far beyond the measure of what can usually be expected. Without their staunch and committed assistance, this volume could not have been published in time. Thank you so much, you have done a fantastic job!

Introduction: Current Debates and British Drama since 2000

Kerstin Frank and Caroline Lusin

Compared to other, more recent media, the traditional theatrical setup seems curiously outdated, almost quaint: both actors and audience are actually physically present in one room, the audience is (for the most part) silent, passive, and receptive, and the actors perform something previously written, re-written, studied, and rehearsed over a considerable period of time. How does this time-honoured layout fit into a fast-moving, globalised world, in which people’s need for interactive social self-construction is manifested in Facebook identities, and in which Twitter satisfies a predilection for quick, short, snappy, fast-travelling responses to events? How can theatre keep pace with social debates that can unfold and spread within seconds of a single event or just in a casual tweet? How can it continue to be a relevant site of collective self-reflection in Britain?

Because, curiously, it is still relevant, and very much so. The original and creative contributions to the stage by new talents as well as by more experienced writers bear witness to the “rude health of current playwriting” (Sierz, “Introduction”, xvii). The theatre is still a vital part of British culture. In fact, Andrew Haydon even testifies to “something of a qualified ‘golden age’ [of British theatre] in the 2000s, both artistically and economically” (40).1 Media attention to first nights and theatre awards remains extensive, and provocative performances continue to spark heated debates. Reviewing a number of such contentious responses, Aleks Sierz concludes: “In each of these cases, the controversy proved that theatre could be a powerful way of showing us who we are, and that disagreement about such depictions were arguments about our national identity.” ( Rewriting , 144) Theatre, in other words, remains a significant diagnostic tool in tackling the challenges Britain faces in the new millennium.2 It has proven particularly apt to negotiate the topic of national and cultural identity or the ever-contested concept of ‘Britishness’. The editors of The Methuen Drama Guide to Contemporary British Playwrights hence argue that “British playwriting has historically had a close affinity […] with the structures of British society, and especially with a more general discussion of economic, social and political issues” (Middeke/Schnierer/Sierz vii). This affinity certainly continues into the 21 stcentury, and the essays contained in this collection propose to explore what drama can specifically contribute to this discussion.

This collection of essays considers drama as a site of social debate, focusing on the unique ways in which plays participate in public discourses about the most pressing concerns of the new millennium. We believe that the dramatic form is singularly equipped to bridge the ever-widening gaps between different other sites of discourse, such as highly specialised, academic institutions and those sites open to a wider field of contributors, such as the social media. Referring to recent black British plays, Lynette Goddard makes a similar point:

These plays raise debates that would otherwise mainly be accessible through long government policy tomes and/or in ethnographic and sociological research studies. Staging these issues through playwriting renders them accessible and open to scrutiny from those who might not otherwise gain access to the complexities of these issues. (16–7)

In other fields, such as science, finance, and politics, playwrights can also distil their ideas and research into dramatic forms that are more easily intelligible but still knowledgeable and well-balanced. While plays cannot react as directly and spontaneously to events as other media, they create more serious and sustainable links between their audience and specialised discourses, without constraining the complexity and accuracy of these.

And then, of course, there is the creative and aesthetic factor, or the question of form. Lynette Goddard slightly overshoots the mark by suggesting “that we can […] look at these plays as quasi-sociological treatises of our times” (16). While plays can certainly mediate information from sociology and other fields to their audience, they will always add something more to it. Plays transform abstract issues into particular situations and plotlines and map them onto dramatic space and characters that allow or demand sympathy or some other form of emotional engagement. They present national or global matters in the light of their consequences for individual people, and they may foreground the ambivalence of moral choices. Beyond the basic, traditional dramatic ‘ingredients’ of characters, stage, and language, contemporary playwrights have incorporated various media, new types of venues, and different forms of engaging with the audience in order to shape and convey their topics in ways that are both emotionally and cognitively relevant to the individual observer. Indeed all traditional features of drama mentioned above have been challenged by introducing experimental alternatives.3 In the words of David Lane, many playwrights “are breaking through the staid and restrictive image of being simply autonomous providers of a list of lines” (1) for the benefit of “moving closer towards what we might refer to as ‘performance writing’: a space where writers explore and develop their work in a direct and active relationship with other practitioners and spaces” (ibid.). Among the plethora of different forms, verbatim theatre stands out as a particularly productive subgenre at present, but playwrights take their inspiration and techniques from a variety of different genres (cf. Adiseshiah/LePage 3).

Читать дальше