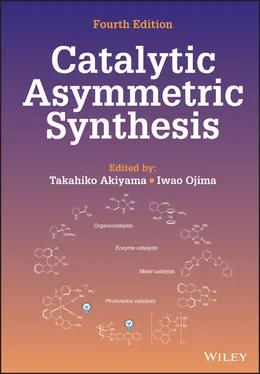

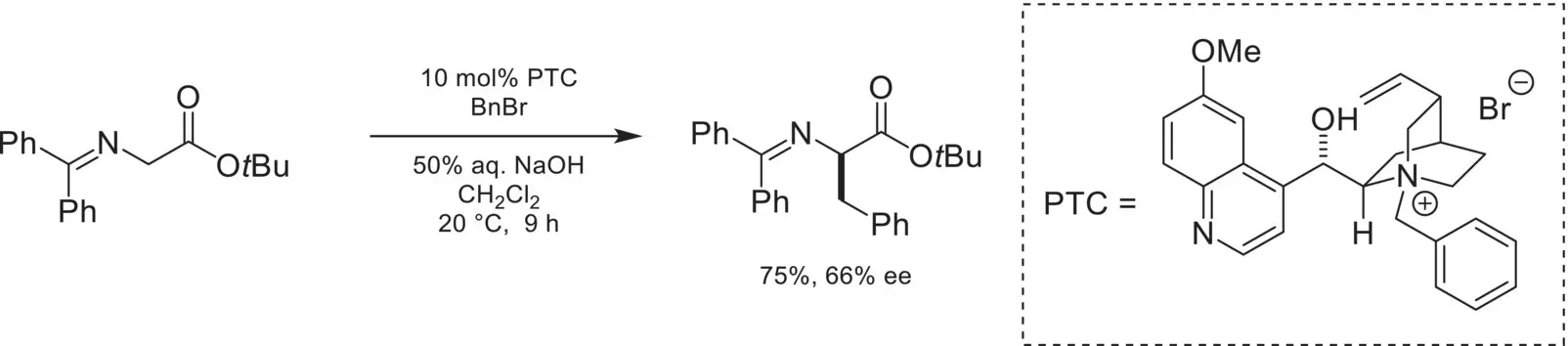

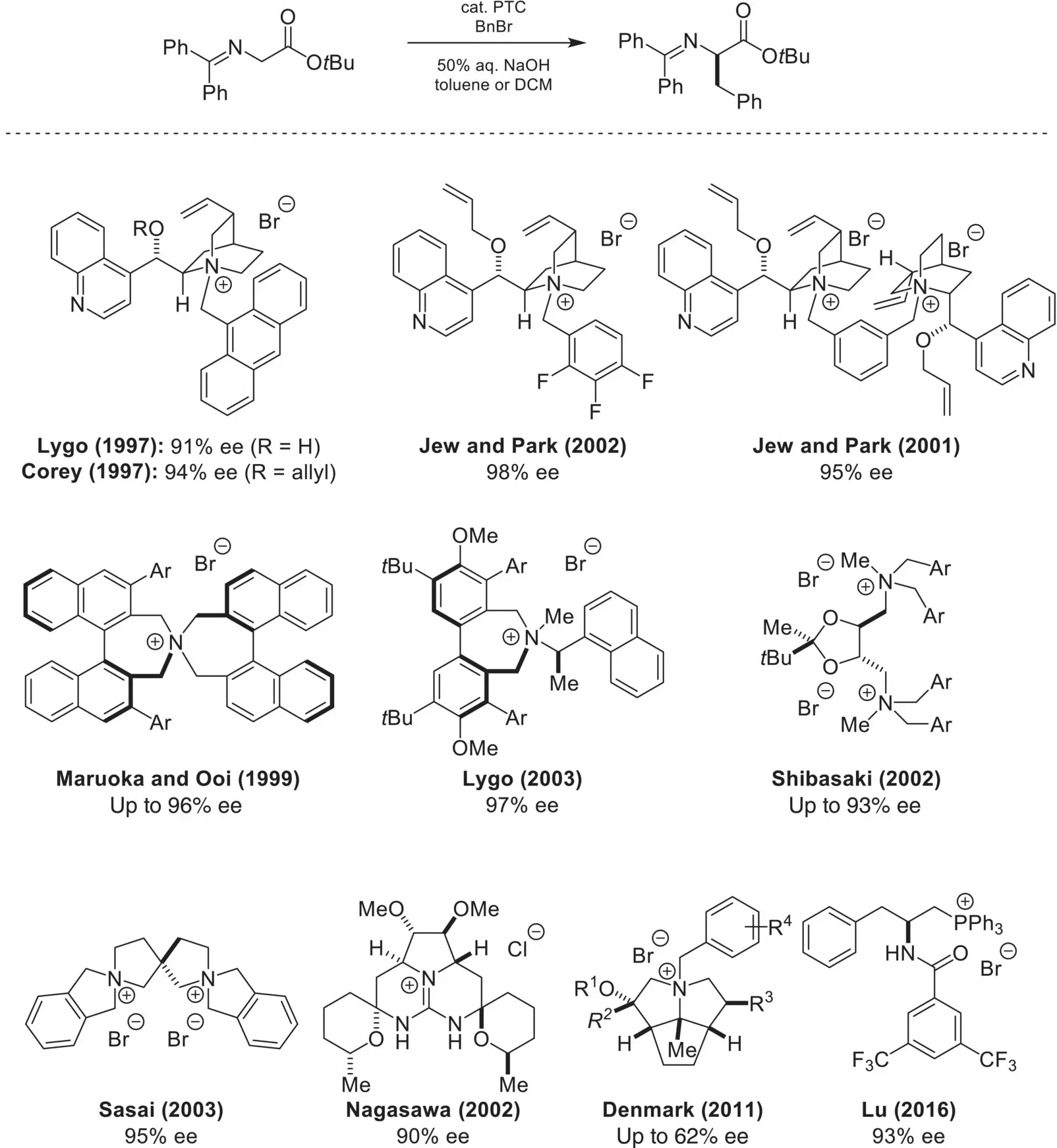

Scheme 4.3. Enantioselective benzylation of glycine imines.

Source: Based on [3].

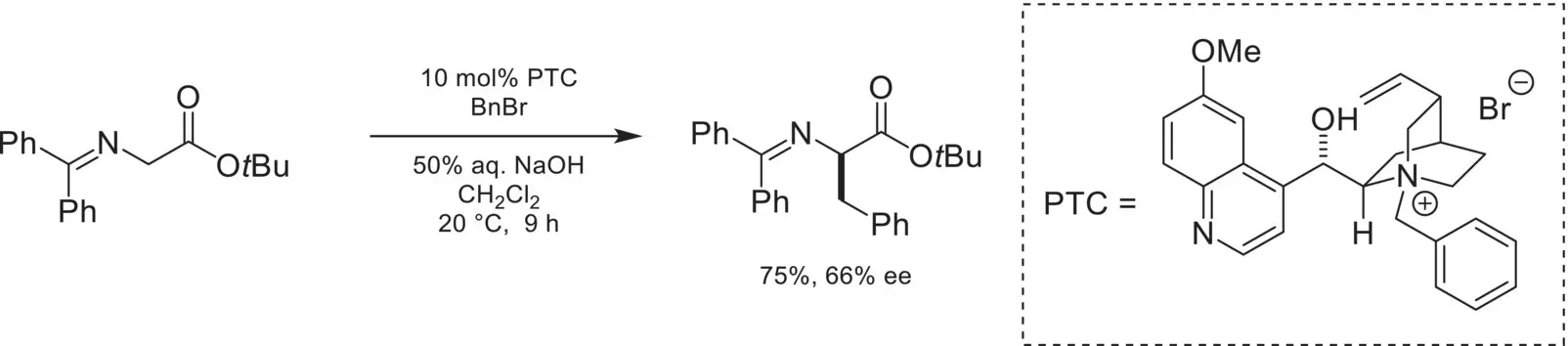

Scheme 4.4. Catalyst development for the enantioselective mono‐alkylation of glycine imines.

Concurrently, efforts by a number of groups aimed to explore catalyst architectures that significantly differed from cinchoninium alkaloids. In 1999, Maruoka reported the use of C 2‐symmetric chiral ammonium salts derived from binaphthyl backbones [12]. High enantioselectivity (up to 96% ee) was achieved with this family of catalysts and marked the first departure from previously reported cinchoninium catalysts. Later, the same group reported a related catalyst wherein one chiral binaphthyl group is replaced by a more flexible achiral biphenyl group, which also achieved high enantioselectivity (94% ee) [13]. Building on this, Lygo reported in 2003 a structurally distinct chiral ammonium catalyst based on a simple biphenyl backbone, where the chiral element originates from a chiral benzylic amine [14]. Due to the scaffold’s modular synthesis and ease of diversification, a small library of ammonium catalysts was synthesized and benchmarked against the enantioselective benzylation of glycine imine. The optimal catalyst featured an α‐methylnathphtylamine group and proved to be highly enantioselective (97% ee). In 2002, Shibasaki reported a tartrate‐derived bis‐ammonium catalyst that proved to be highly enantioselective for the same reaction (93% ee) [15–17]. The hypothesis was that the tert‐butyl glycinate anion would preferentially orient itself between both ammonium centers, leading to enantiotopic face discrimination. Monte Carlo molecular mechanics simulations were consistent with this substrate‐catalyst binding mode. In 2003, Sasai reported another dicationic bis‐ammonium catalyst based on a spirocyclic bis‐pyrrolidinium scaffold, which also proved to be highly enantioselective in the same reaction (95% ee) [18]. In 2002, Nagasawa reported pentacyclic guanidine salts as efficient catalysts for the same reaction (90% ee) [19]. Hydrogen bonding interactions with the glycinate anion are proposed, which allow for high levels of enantioinduction. In 2011, Denmark disclosed a family of tricyclic ammonium catalysts that proved to be moderately enantioselective (up to 62% ee) [20]. Most recently in 2016, Lu reported that quaternary phosphonium salts derived from amino acids were highly efficient catalysts for the benzylation of glycine imines (93% ee) [21].

The use of benzophenone‐derived imines in the enantioselective phase‐transfer catalyzed alkylation reactions described above allowed for exclusive mono‐alkylation selectivity over bis‐alkylation and avoided product racemization. This is due to the lower C–H acidity (p K a~23) of the mono‐alkylated benzophenone imine product compared to the nonalkylated starting material (p K a~19) [22]. The stark difference in acidity can be rationalized by unfavorable allylic 1,3‐strain between the benzophenone imine phenyl group and the α‐alkyl substituent, forcing them out of plane and reducing stabilization of the azaallyl anion.

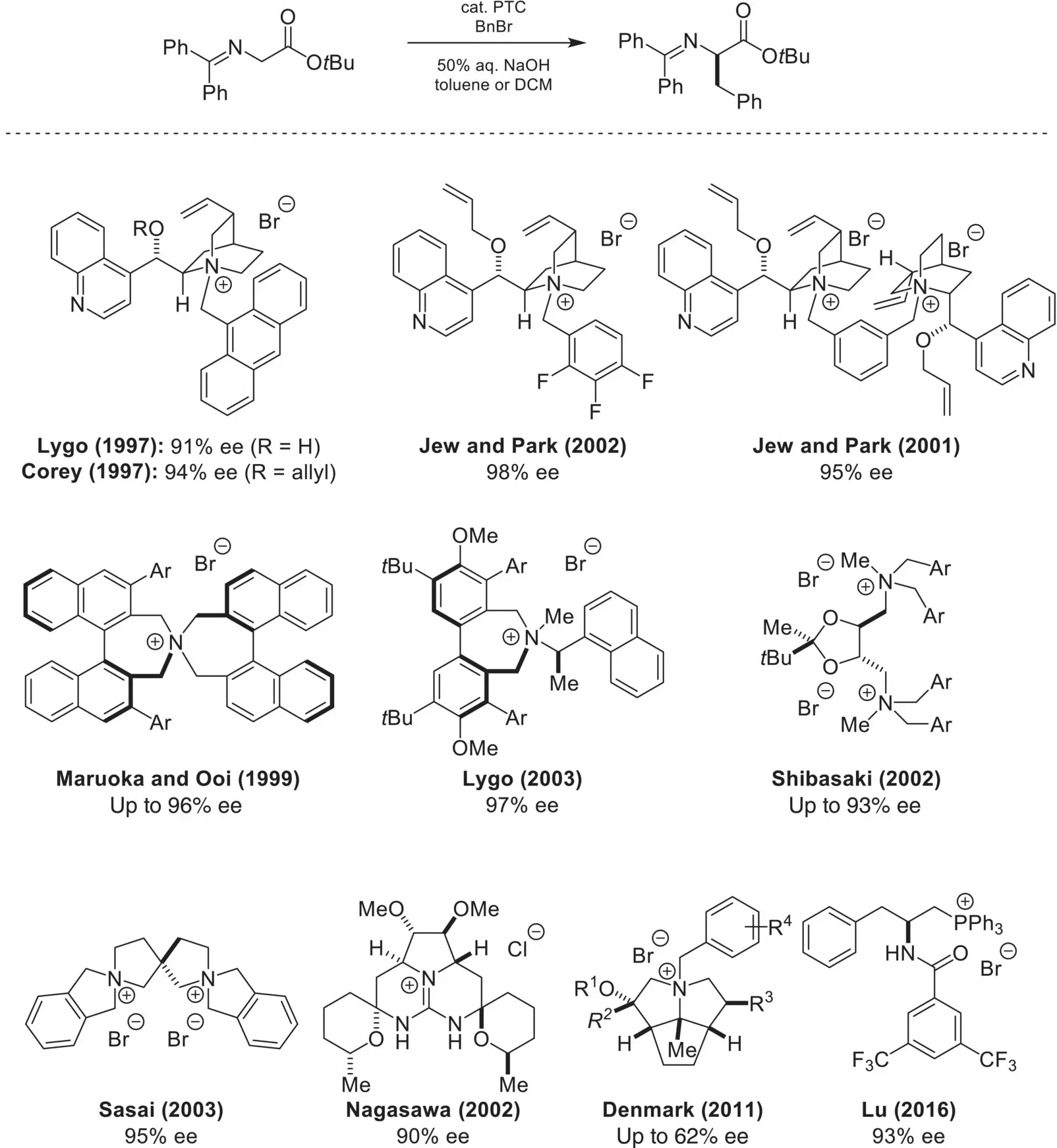

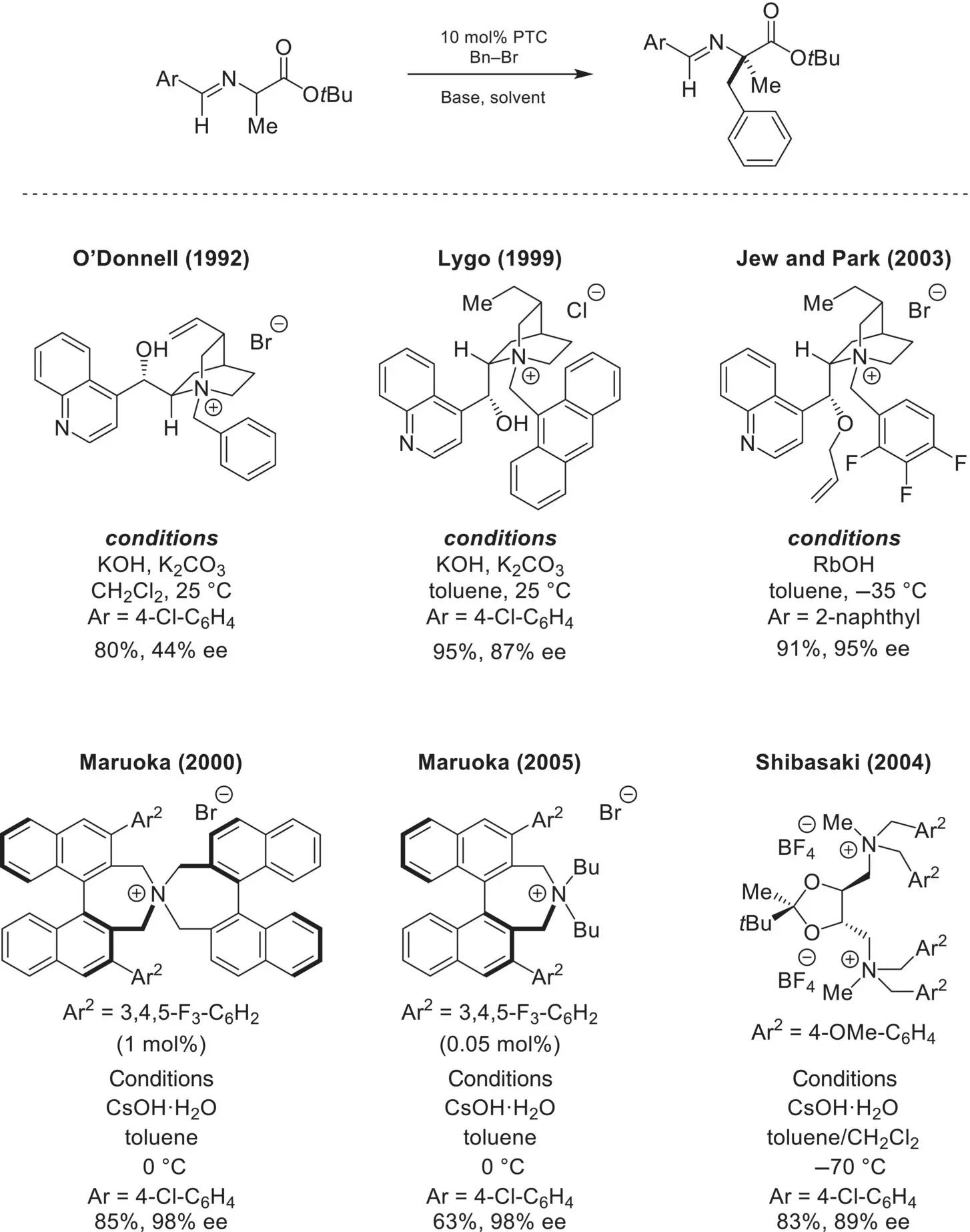

Modification of the benzophenone imine to an aldimine derivative allowed for the formation of α,α‐dialkylated products ( Scheme 4.5). In 1992, O’Donnell reported the first enantioselective alkylation of α‐alkylated amino acid aldimines to from α, α‐dialkylated amino acids [23]. Tuning of the catalyst by Lygo et al. [24] and later by Jew and Park [25] allowed improved enantioselectivity for this reaction. Notably, Jew and Park’s conditions included more basic RbOH that provided high enantioselectivity (95% ee) for this reaction. Maruoka reported that chiral‐bisnaphthyl‐derived ammonium catalysts also catalyzed this reaction at impressively low catalyst loadings (as low as 0.05 mol%) while providing very high enantioselectivity (98% ee) [26, 27]. Under similar conditions, Shibasaki reported the use of a tartrate‐derived bis‐ammonium catalyst that provided high enantioselectivity, however required low temperature (–70 °C) [16].

While α‐amino acid imines have arguably been the most explored class of substrates for enantioselective phase‐transfer catalysis, enolates derived from ketones, esters, and amides have also successfully been used in such transformations. Furthermore, numbers of different alkyl electrophiles, both activated and unactivated, have been reported in such transformations. These will not be comprehensively discussed in this chapter, but can be found in more detailed reviews on the subject [28]. Overall, successful implementation of enantioselective phase‐transfer catalysis for enolate alkylation hinges on controlling mono‐alkylation and bis‐alkylation, while avoiding product racemization.

Beyond enantioselective enolate C‐alkylations described previously, selective O‐alkylation can also be achieved via chiral phase‐transfer catalysis ( Scheme 4.6). In 2017, Smith described a strategy to access unsymmetrical 1,1′‐bi‐2‐naphthol (BINOL) derivatives [29]. A chiral cinchoninium catalyst was found to promote the highly atropselective enolate O‐alkylation of tetralone derivatives with only traces of C‐alkylation observed. Oxidative aromatization with DDQ afforded unsymmetrical BINOL derivatives. An investigation of the mechanism by density‐functional theory (DFT) suggests two hydrogen‐bonding interactions between the tetralone enolate and the cinchoninium (OH group and benzylic C–H) are involved in the enantiodetermining O‐alkylation [30].

Scheme 4.5. Catalyst development for the enantioselective synthesis α, α‐dialkylated glycine imines.

4.2.1.2. Addition to Michael Acceptors

In the early years of asymmetric cation phase‐transfer catalysis, significant focus was dedicated to enantioselective enolate alkylations with alkyl halides. Soon afterward, it was recognized that this strategy had broader potential. Once generated, the enolate/catalyst ion‐pair could be matched with a number of other classes of electrophiles, with Michael acceptors being an early example ( Scheme 4.7). In 1998, Corey reported the use of an anthracene‐functionalized cinchoninium catalyst for the enantioselective addition of a diphenyl glycine ester to acrylates, and later acrylonitrile derivatives [31, 32]. A few years later in 2002, Shibasaki reported the use of a tartrate‐derived chiral bis‐ammonium catalyst for the same class of reactions [15]. In the same year, Arai and Nishida reported that an N‐spirocyclic ammonium catalyst was also a competent catalyst for this reaction, albeit affording moderate enantioselectivity [33]. In recent years, Maruoka reported the use of bifunctional chiral ammonium salts to catalyze the enantioselective addition of nucleophiles to Michael acceptors such as nitroolefins[34–36] and maleimides[37, 38] under neutral conditions. The successful implementation of this base‐free phase‐transfer strategy hinged on the use of water‐rich solvent mixtures proposed to allow formation of the key reactive catalyst‐substrate ion‐pair. This strategy was later extended for successful asymmetric aldol, chlorination, and sulfenylation reactions [39, 40].

Читать дальше