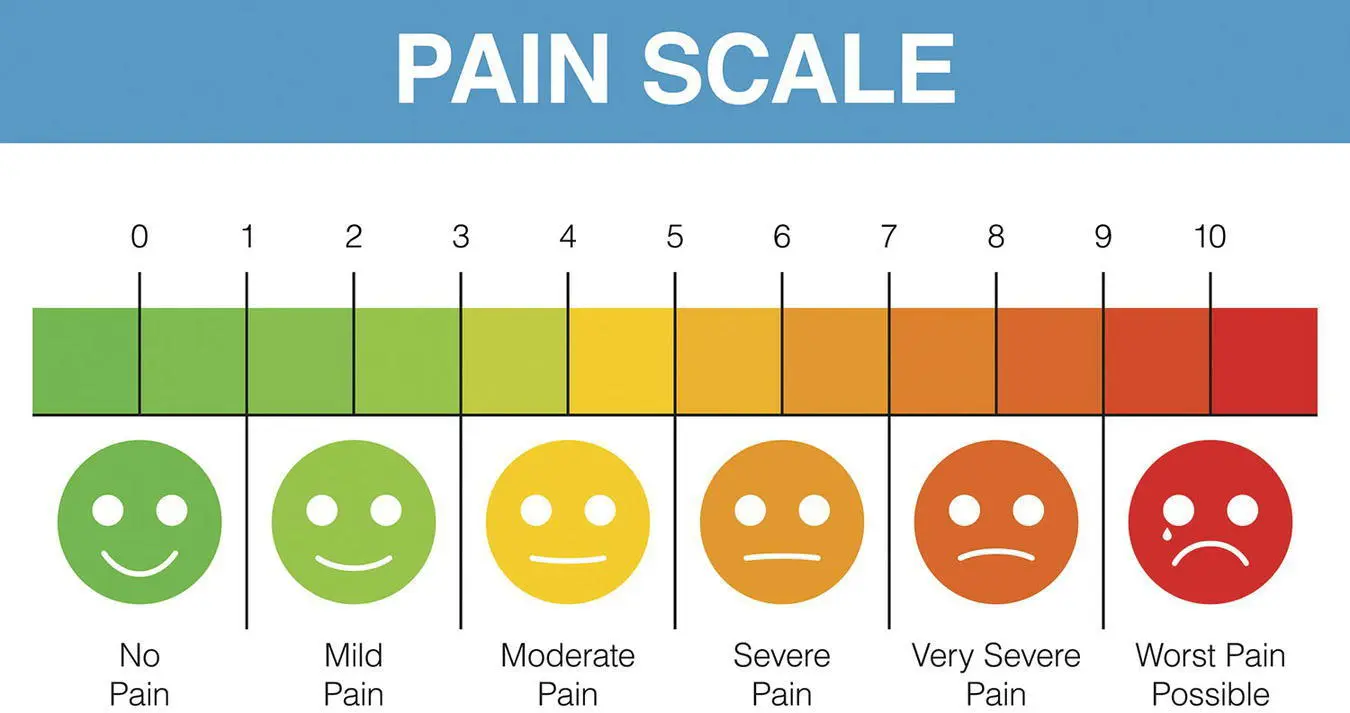

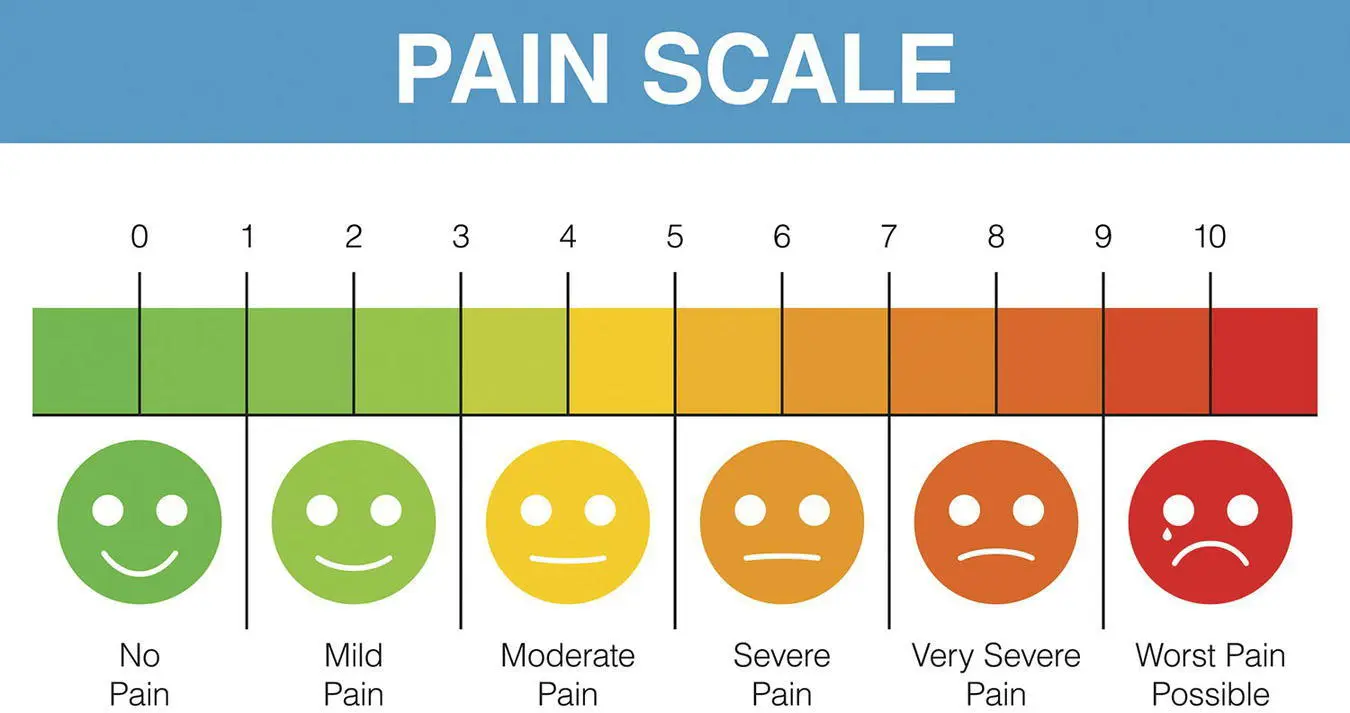

FIGURE 1.1 The 10‐point pain scale (Harvard Men’s Health Watch, 2018).

Source : Image: © EgudinKa/Getty Images.

Can you imagine, one patient says to another:

P1:

How're you feeling today?

P2:

Not great – I've got a grade 8 pain!

P1:

Gee, I'm sorry to hear that! What axis are you measuring it on?

Those who believe that there is only one reality and that this reality exists independently of our knowledge of it are called positivists.Those who believe that all reality is subjective are called relativistsor interpretivists.To me it does not make sense to say, ‘I believe that all of “reality” is subjective’, any more that it makes sense to me to say ‘I believe that all of reality is objective’. But, I acknowledge that other people have different views. For me, life is too short to bother with them. And that's all I want to say about that.

Epistemologyis the study of what constitutes ‘knowledge’. It is concerned with defining the nature of what knowledge is and how we know things. So, the epistemologist will be concerned about different views on knowledge, beliefs, truth, justification, and internalism/externalism. (Don't even ask!)

In relation to research methods, if you hold a positivistbelief (note my use of the term ‘belief’) then you are likely to want to have proof for your knowledge in the form of things you can see, touch, and get confirmation from others that they see and touch them too. You are likely then to favour methods which measure things and count things and to use statistics to analyse your data. One criticism is that they reduce everything to a number:

Nrs:

What's your depression like today?

Ptnt:

It's a seven .

Nrs:

Oh my, that's bad, I'd better get you some more pills!

If you hold an interpretivistbelief, then you will not search for absolute proof for your knowledge, because you don't think that that exists. Therefore, you will be inclined to use inductive methods and qualitative approaches, because you recognise the subjectivity of your unique location in time (history) and society (class, gender, race, culture, etc.). You won't try to measure pain, or depression just by numbers. You might say ask questions like:

Nrs:

Can you describe your pain to me?

A third paradigm (way of thinking) is a pragmatistbelief. This accepts aspects of both positivist and interpretivist beliefs and can adapt to the most realistic means of addressing an issue using either positivist or interpretivist approaches.

Methodologyrefers to the broad approach which we take to guide our collection of data. The three main categories are quantitative (numbers), qualitative (no numbers), and mixed‐methods (whatever you want).

Methodsrefers to the actual means of collecting your data – for example by measurements, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, focus groups, and so on.

They are linked, and I have tried to show a relatively simple way of thinking about it in Table 1.1. (I was inspired By Salma Patel's 2015 model which I have adapted here.)

The main distinctions we tend to make in research are about:

positivist vs interpretivist

quantitative vs qualitative

hypothetico‐deductive vs hypothetico‐inductive.

And if you bear those distinctions in mind, you'll get by!

Research can exist outside of our knowledge of ontology and epistemology. Don't fret too much over these complex ideas. As you might end up debating whether it is positivist or relativist to decide how to count the number of angels you can get on a pinhead …

TABLE 1.1 Ontology, epistemology. Theoretical perspective, methodology, and methods.

Source : Adapted from Patel (2015).

| Research Paradigm |

Ontology |

Epistemology |

Theoretical Perspective |

Methodology |

Methods |

| Positivist |

There is a single reality |

Reality can be measured using the best scientific methods |

Positivism |

Quantitative methods – experimental and observational hypothetico‐deductive |

Sampling, measuring Numbers and statistics |

| Interpretivist |

No single reality. Reality depends on the researcher's location in time and society |

Everything is subject to interpretation. We need to discover how people experience their worlds |

Interpretivism |

Qualitative methods: phenomenology ethnography grounded theory Etc. Hypothetico‐inductive |

Participant observation Interviews Focus groups Etc. |

| Pragmatism |

Reality is constantly being re‐negotiated and interpreted |

You can choose the best method for solving the problem |

Pragmatism |

Mixed methods |

Any methods which will answer the question |

For further reading, if you have the mental stamina to be confused further, you might look at: Devaux and Lamanna (2009), Griswold (2001), Heidegger (1971), Sturm (2011), Descartes (1985), and Haack (1993).

1 Descartes R. (1985). The Philosophical Writings of Rene Descartes I. Cambridge University Press.

2 Devaux M and Lamanna M. (2009). The rise and early history of the term ontology (1606–1730). Quaestio 9(173–208), 197–198.

3 Griswold CL. (2001). Platonic Writings/Platonic Readings. Penn State Press, p. 237.

4 Haack S. (1993). Evidence and Inquiry: Towards Reconstruction in Epistemology. Wiley‐Blackwell.

5 Harvard Men’s Health Watch. (2018). The pain of measuring pain: Doctors and patients use the 10‐point pain scale to gauge the severity of pain, but there may be a better way.’ Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/the‐pain‐of‐measuring‐pain(accessed 25 September 2020).

6 Heidegger M. (1971). On the Way to Language. Harper & Row: New Yor, (original: 1959).

7 Patel S. (2015). The research paradigm – methodology, epistemology and ontology – explained in simple language. Available at: http://salmapatel.co.uk/academia/the‐research‐paradigm‐methodology‐epistemology‐and‐ontology‐explained‐in‐simple‐language(accessed 25 September 2020).

8 Sturm T. (2011). Historical epistemology or history of epistemology? The case of the relation between perception and judgment. Erkenntnis 75(3), 303–324.

CHAPTER 2 Experimental Quantitative Approaches: Laboratory Experiments

Introduction

I guess that most of us can remember laboratory experiments from our school days – unless, as some do, you have blanked this out! Laboratory experiments are:

In the quantitative domain – we measure and count, we use numbers.

They are usually hypothetico‐deductive – we have a clear purpose and set of expectations in mind before we begin.

They are in the interventional domain – we introduce an experimental variable which was not there at the start.

They are prospective – we have a start point where we make our initial measurements, we have our interventions, and we have an end point when we make our final measurements.

They are best suited to answering questions like: ‘If I add/change this, will that happen?’

Читать дальше