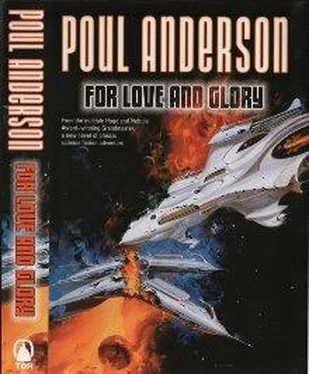

For Love and Glory

by Poul Anderson

TO GEOFF KIDD

for help above and beyond the call of friendship

A dozen years ago, the late Isaac Asimov created a science fictional cosmos to serve as a narrative background for other writers. It was interesting to see how differently they handled it while trying to stay consistent with the premises. I contributed to two of the ISAAC’S UNIVERSE volumes, The Diplomacy Guild (1990) and Phases in Chaos (1991). Now Janet Asimov and editor Martin Greenberg have graciously given me leave to incorporate these stories in an independent novel.

It has turned out independent indeed. The concept of several intelligent spacefaring species, who come upon relics of unknown predecessors, is still there, but that is scarcely unique in our literature. Otherwise little remains except that pair of episodes, much altered. To avoid conflict with anything in the original series or constraining any future volumes, the history, the races involved, the individual characters, most place names, and the general course of events have all been changed. This tale stands entirely on its own.

Still, I wish to acknowledge my debt to Isaac, Janet, and Marty.

—POUL ANDERSON

At first sight Lissa thought it was an island—a strange one, yes, but this whole world was strange to her. Then as she and Karl came out of the woodland and went on toward the river, she knew it could not be. It lay in midstream, dully iridescent, about twenty meters long, perhaps a fourth as wide, curving up to a gently rounded top one meter or so above the water. Someone or something had made it.

But there were no native sophonts anywhere around this star. Scant though exploration had been in the seven Terran years since the system was first visited, that much was certain.

So who, and when, and why?

She halted. “What the chaos? Have you any idea what that might be?”

Karl stopped too. “None,” he said. “I do not recall any such artifact from my experience or other sources of information. A slight resemblance to some dwellings of the Orcelin civilization.” The tip of his tail gestured at the camp near the shore. “Obviously it is not the work of yonder persons. I presume they are studying it. They may have learned something.”

The translator clinging to Lissa’s backpack rendered his answer into flat-voiced Anglay. He could follow her words readily enough. If he had tried to utter them the result would have been grotesque. For her part, she could not hear most of his language, let alone pronounce those trills, whistles, and supersonic melodies. Once it had struck her funny that such a huge creature should have so thin a voice. But that was in her silly girlhood. She had since met beings much more paradoxical and less comprehensible, and learned that to them humans were likewise.

She did still sometimes wonder whether Karl—her name for him, honoring a friend at home—really spoke as academically as the device rendered it. He was a scientist, but also a top-class waymate. Yet she would never understand the nuances of his personality, nor he hers. They could never be more than comrades.

“Let’s have a better look.” She unsheathed her optic, raised it to her eyes, and activated it. His keener vision had already made out what she now did. The surface was not actually smooth, it was subtly, bewilderingly complex. Increasing the magnification gave small help. Noontide shadows were too short to bring out enough relief.

The idea struck her like a fist. Her hands dropped. “Forerunner work?” she cried.

Amidst the tumult in her head she felt that the translator’s level tone was, for once, conveying an emotion. Calm. “I immediately suspected so.” Somebody with Karl’s size and strength might not be very excitable. Interested, yes; delighted, maybe; but free of the chills that ran up her spine, out to the ends of her fingers.

Steadiness returned. She lifted the optic again.

Two beings poised on the thing, with a variety of instruments set forth. One was a male human, the other an anthropard from Rikha or a Rikhan colony. She watched them come to full alertness, peer her way, and hasten down the whaleback curve. Their boat lay alongside, tethered by a geckofoot grapnel. They got in, cast off, and motored toward the land.

Lissa swung her gaze about and found their camp, which from here was half screened by brush. She put her optic back.

“Do you recognize either of them?” asked Karl.

“No,” she said, “nor why they haven’t been in touch.” She scowled as she started off again. “We’ll find out. We’d better.”

The camp amounted to three dome shelters. But the vehicle standing by was no ordinary flyer adapted for this planet. Twice the size, it was clearly capable not simply of flitting through atmosphere, hovering, vertical landings and takeoffs, but of making orbit. Indeed, when last she and Karl heard from headquarters, personnel had detected a small spaceship circling farther out than theirs in a sharply canted plane. Apparently those who had been aboard would rather not be noticed.

Otherwise the landscape lay primeval, hills rolling low in the east and on either side of the valley, thickly wooded. The vegetation was unlike any she knew of anywhere else, curiously shaped boles and boughs, foliage in shades of dark yellow and brown, eerie blossoms—another world, after all. Animal life was as alien and as abundant; the sky was full of wings and clamor. The fundamental biochemistry resembled hers in a number of ways, and the basis of life itself was microbial here too. But that was due to the working of the same natural laws on more or less Earthlike planets. How many centuries until the biology of even this single continent would be even sketchily charted?

Depends partly on how much of an effort scientifically oriented sophonts feel is worth making, passed banally through her mind. The galaxy’s so huge, so various, and always so mysterious.

Odd, how high and steep the riverbanks were. In fact, it flowed at the bottom of a rocky canyon. Farther inland, its sides were low, begrown to the very edge of the water. Only as she neared did she see that here the stream had broadened to almost a kilometer.

She reviewed the local geography as scanned by a satellite. Flowing westward, the river became wider still. Fifty kilometers hence its estuary was salt marshland. There it emptied into a channel that in turn led to an ocean.

Evidently local topography had made it cut this gorge. Hadn’t that taken time on a geological scale? But the rock wasn’t wind-sculpted, merely littered with boulders where ledges and cracks offered resting places.

Nor was the ground above richly forested, like upstream. A strip of thin, poor, rocky soil reached back some fifty meters from either verge. Tough-looking, deep-rooted little bushes stood sparsely, interspersed with lesser plants that she guessed were evanescent opportunists. She saw just a few tiny animals scuttering between, though winged creatures continued plentiful. The camp was at the edge of the semi-desert, half surrounded by fairly large shrubs, trees behind it.

One of countless puzzles.… At the moment, she had too much else to think about. Surely in due course somebody would reason this out.

She eased her pace. In spite of a noticeably denser atmosphere and higher partial pressure of oxygen, in spite of her being in athletic condition and having trained beforehand, a surface gravity fifteen percent above Earth normal added nine kilos to her weight.

Karl slowed to match her. By his standards, he was taking baby steps. Carrying nearly all their field equipment on his back, as well as his own mass, he seemed to move effortlessly.

Читать дальше