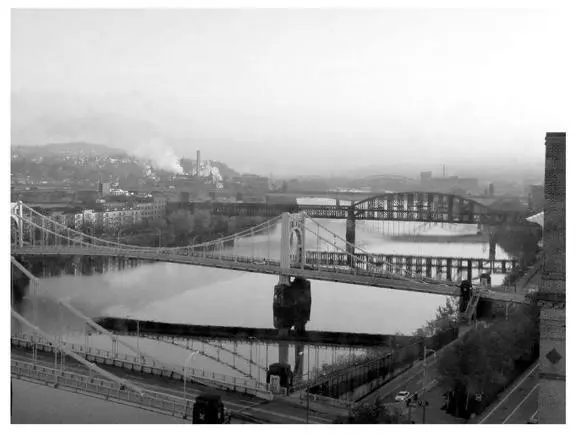

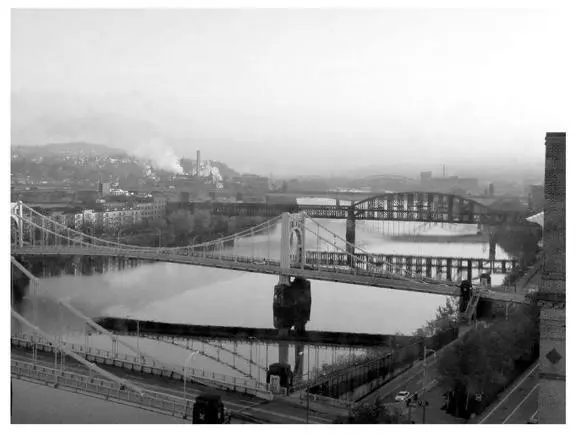

Sometimes a rebirth can be started in one neighborhood and then it spreads to the surrounding areas—if they’re not cut off or isolated. Artists move into a former factory district and soon cafés and grocery stores follow. A music club opens, a gallery and a bookstore. Developers turn the warehouses into luxury condos and the process begins again, somewhere else. Or, as in some downtowns like Kansas City’s, a local impresario might decide to put shows in someplace like the Uptown Theater, a venue in a sketchy part of town that was on the verge of being torn down. A business opportunity and a show of faith. A bar opens close by, a record store, and before too long the area has begun to be more livable. One significant investment can sometimes trigger a chain of events. The Heinzes have done something like that in downtown Pittsburgh, renovating theaters and arts centers, which have attracted other businesses. It’s working.

Though I have tended to paint a bleak picture, not every city in the U.S.A. is going to hell in a handbasket because of dying industry, stupid planning decisions, or racially motivated white flight. It doesn’t have to be that way. San Francisco, Portland, much of Seattle, much of Chicago, Minneapolis, Savannah, and many more are vibrant and full of life. These are places where things are turning around, where the quality of life has completely returned, or where it was never allowed to be destroyed. Strangely, the recent economic downturn might be a great opportunity. Sustainability, public transport, and bike lanes aren’t scoffed at anymore. Congressman Earl Blumenauer, a longtime advocate for biking as a means of public transportation, thinks now is the time.

Some of these other cities I visited might come back too. Often it only takes some political will and one or two significant changes and then things begin to change by themselves. Cities as a rule use less energy per capita than do suburban communities where people are living spread out, so as the cost of energy spirals up, those grimy urban streets start to look like they might have possibilities. The economy has tanked, the United States can lose its place as number one world power, but that doesn’t mean that many of these cities can’t still become more livable. Life can still be good—not only good, it can be better than what most of us can imagine. A working-class neighborhood can be full of life. A neighborhood that has many different kinds of people and businesses in it is usually a good place to live. If there were some legislation that ensured that a mixed-use and mixed-income neighborhood would emerge when developers move in, it would be wise, because those are the liveliest and healthiest kinds of communities.

Berlin

Nostalgia for the Mud

Flying into Tegel Airport in Berlin I look down at the neatly ordered fields and roads—even in the surrounding forests the trees are in neat rows—and I think to myself how this entire country, the landscape, everything as far as one can see, has been ordered. There is no wildness, chaos, or funkiness, not here or much of anywhere in industrialized Europe. Man is in charge and has, over many centuries, put nature in its place. In many countries there is an ethos that complements this gardener point of view—an ethos that values wildness. So as a result there are isolated parks and protected areas—like green zoos—here and there.

I remember in 1988 scouting the German countryside for film locations for a movie called The Forest that the theater director Bob Wilson and I had hoped to make. At that time the Wall was still up, but I managed to scout locations in the East as well, which made the scouting job fun and challenging. Given the title of the piece, inevitably there were to be scenes in a virgin forest, so I went looking for one. In all of Germany we found one piece of virgin forest—a preserved one-kilometer-square roadside tract.

It was indeed different, very different, from all the other forests we had seen. None of the trees were straight; they were gnarled, twisted, and had evidently led interesting lives. The forest floor was littered with massive dead and rotting trunks—twisted corpses, the ancestors of those giants still standing. It was just like the forests described in fairy tales or seen in certain movies—chaotic but almost comforting, creepy but beautifully alluring. One felt that one was inside of a creature and outside of it at the same time. As if one were walking around the innards of a huge being. A bit sad, I think, that my visual reference for an unmediated forest derives from images in fiction and movies. Sad too that the forest in this preserved area was once quite common, but now lives on mainly in our collective imaginations—an image burned into our psyches over millennia, indelible, but now having little relationship to the real world. This little parcel was the only one left—except for a rumored larger forest in Poland, but going there to shoot would have been impractical.

Europe is manicured. The whole continent, except for some semi-accessible places in the Alps, northern Scotland, and Scan dinavia, has been groomed and tended by the hand of man. It’s a vast millennial project, this custodial effort, requiring the cooperation, over centuries, of scores of nations and peoples, all speaking different languages and with different cultures. The greatest physical human enterprise of all.

America has nothing like it. There is no historically manicured landscape except maybe in the aptly named New England, or perhaps parts of the Great Plains, where the steppes of North America have been organized by agribusiness. America still has, lurking around its edges in tattered remnants, bits of unkempt wildness and danger. Even in places where that wildness is illusory it still exists within living memory, at least for now—people therefore internalize its existence and act as if it is still there, and behave accordingly. The seductive and dangerously chaotic and capricious unknown lies just beyond the farmland in many places—or is at least remembered as being there not so long ago.

Europeans’ attitude toward their landscape is to cultivate the continent as if it were a vast garden, while Americans prefer to subdue the landscape by force, paving over vast areas, or planting miles of a single crop—like corn—that stretch to the horizon. In the New World it is assumed that there will always be more land over the horizon, so sustainable cultivation and conservation are often viewed as namby-pamby. I suppose a lot of Russia and the former Soviet republics are like this too, which might explain a thing or two. Maybe that’s why lots of North Americans feel that the whole world has to be tamed and brought under control while Europeans, having more or less achieved that control in their own lands, feel a duty to nurture and manage rather than simply subdue. Industrialization and agricultural subjugation throughout most of Europe is now a thing of the past—its legacy a nasty memory of polluted rivers and blackened skies, many of which are now being cleaned up, sort of.

I ride my bike along the bike lanes here in Berlin and it all seems very civilized, pleasant, and enlightened. No cars park or drive in the bike lanes, and the cyclists don’t ride on the streets or on the sidewalks either. There are little stoplights just for the bikers, even turn signals! (Cyclists often get to turn a few seconds before the rest of the traffic, to allow them to get out of the way.) Needless to say, most cyclists here do stop for these lights. Pedestrians don’t wander into the bike lanes either! I’m kind of in shock—it all works so well. Why can’t it be like this where I live?

Читать дальше