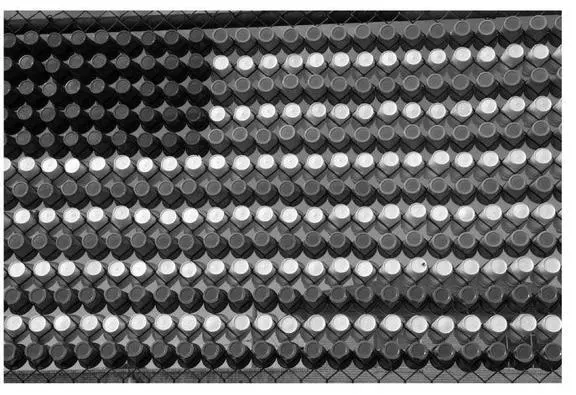

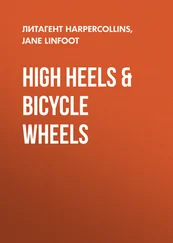

There are people selling watermelons in a shopping-center parking lot, next to a U.S. flag made of plastic cups jammed into a fence.

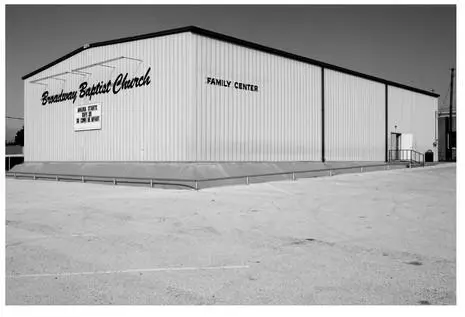

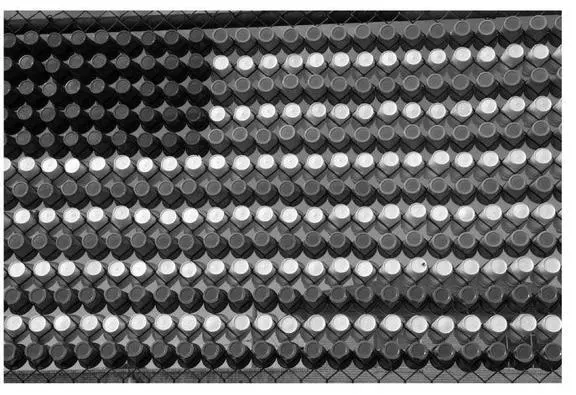

Down the road is an abandoned drive-in and a church in a prefab metal building with a sign urging visitors to Come Be Apart.

Columbus, Ohio

I bike across a suburban industrial park, which brings me to the backside of a complex that includes a shopping mall and a simulated street filled with restaurants and some condos. Night is just beginning to fall, the sodium vapor lamps are beginning to flicker on, and their orange chemical glow fills the parking lot. The landscaped and perfectly smooth grassy areas have turned a strange color in this odd light. It’s an otherworldly experience gliding through these zones. I’m reminded of a movie in which the pleasant landscaping and the gently curving drives outlined by white curbs hide violent and perverted crimes and secret research taking place within the ubiquitous anonymous modern buildings. No one would take much notice of weird behavior around here. Nothing would look suspicious or out of place. I glimpse an interstate highway briefly through a planted grove of trees. It leads to Cleveland and Cincinnati. The whoosh of the cars and semis passing on it is like distant industrial Muzak, the sound of a mechanical wave machine, or a whispered conversation heard through dense foliage.

This perfect landscape has retained its surface familiarity, virtually, but the deep reasons for its existence—the social and sensual—have been eliminated. Immaculate green shapes fill the dividers on the access roads. The placement of a carefully pruned grove of leafy trees softens the edges of a mirror-walled research facility. Hidden cameras are mounted on posts among the branches, and discreetly posted signs warn of the presence of guard dogs—the only things that betray the seriousness and gravity of whatever goes on inside. Decor and manicured landscaping allude to some memory of landscape—they are a visual “description” of a place, but they are not that place. The sculpted grassy areas and bushes are allusions that “point at” and reference an archetypical bucolic scene. All the proper elements that are needed to constitute a lovely landscape are here, but reduced to signs and symbols. This is an imitation of a planet, with a well-developed culture, where these things originally evolved.

I sense that the same impulse that keeps a bottle of beer or a glass of wine out of a restaurant and that sees radically Spartan architecture as eminently wise has been at work in the landscaping here. The wacky religious fundamentalism that drives much of the United States makes for places that on the surface don’t betray any religious foundation at all. But it’s there, a deep invisible base implicit in the landscaped industrial parks and weird nonspaces that evoke nostalgia for the nonexistent.

A soap opera character on the bar TV says, “You killed him, you smothered him with doughnuts!” Another character, another scene—she is sitting in a room with a man and an elderly woman—the lead character wonders if she’s dead. The man says, “No, you’re alive,” and the other woman hands her a plate of doughnuts.

A commercial comes on. A couple are on a date and the woman’s voice-over articulates interior thoughts of what a wonderful guy her friend has set her up with: “He’s so cute, and his IQ is higher than my bank balance . . . but she didn’t tell me he has . . . Tourette’s syndrome.”

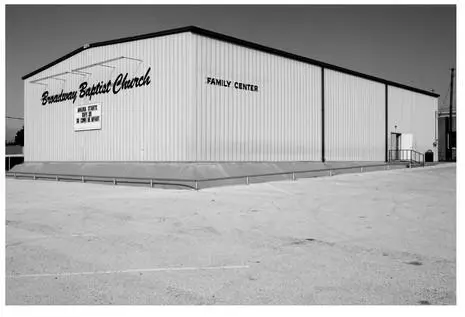

New Orleans—an Alternative

Pre-Katrina I biked around New Orleans many times. The city is pretty flat, which makes it easy on the knees. On one trip I discovered a bike path along the top of some of the earthen levees. It was delightful; one could see the river on one side and the city spread out on the other.

Here there are few of the usual interstates that divide and wound cities. There’s mostly just I-10, on its massive concrete pilings, which snakes into the center of town, desperately trying to stay above most of the funk and humanity below. New Orleans was, and I suspect still is, one of a few large cities across the U.S.A. with character and personality, with its own food, culture, language, and music. It never fails to inspire, though it has clearly flourished despite much neglect and years of abuse that were revealed to the world when the hurricane struck.

I bike along Magazine Street and then on St. Charles where what at first glance appears to be Spanish moss in the trees turns out to be Mardi Gras beads, hanging from the weird branches, block after block—and it’s not even Mardi Gras season.

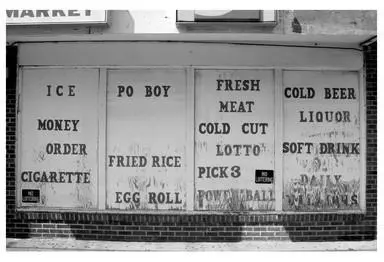

The vibe here is open—people look at you, talk to you, and are incredibly friendly. It’s a bit like Brazil that way, a bit more African, in how people acknowledge one another, certainly more so than Denver or San Diego, where people avert their eyes and are suspicious if you say hello. Though it might seem strange to propose this here in the Deep South, this also seems like one of the least racist cities, in certain respects. I know that can’t be strictly true, but I sense there are more black-owned businesses, cultural projects, and enterprises here—mixed in with the usual white financial hegemony—than in many American cities. I sense a little less of the anger, fear, and suspicion that often permeate American cities—though I’m aware that this is for many also a desperately and inescapably poor city. Hopelessness and violent crime live here too.

I would like to think that some of the positive aspects of this town might be due to its African American heritage, but then I think again of my former hometown—Baltimore—which is largely black, or of Washington, DC, aka Chocolate City, which, when I was growing up, was 70 percent black. Those places, their urban centers, are, outside the government buildings and white enclaves, depressing, sad, and dangerous. There must be other factors at work in this town that have stopped it from going down that same road. Maybe the French Roman Catholic attitude toward sin and pleasure that got mixed in helps make the African sensuality more acceptable down here. My guess is based on its similarities to Latin American cities like Havana, Lima, Cartagena, and Salvador, where the mix of Africa and Roman Catholicism have also produced vibrant music and culture.

I also sense less alienation among people doing their jobs here. Maybe it’s because more businesses are locally owned or maybe people just relate to one another differently. Whatever it is, it’s one of the few U.S. cities that is about living, though the life here is far from easy and much of that life was taken away and the infrastructure destroyed by Katrina and the lack of response. Sad that one of the few large U.S. cities with a unique character was abandoned and left to be washed away.

For many years I found it surreal, amusing, and just downright weird to bike through dead zones, barren suburbs, or downtowns on the verge of becoming ruins. Such strange landscapes have their attraction. But the novelty has worn off a little, and now I’m more drawn to destinations where I can bike on paths in parklands bordering rivers and lakes rather than on the shoulders along expressways, sucking in fumes and risking my life.

The Return of Pittsburgh

Читать дальше