Some people find beauty hard to define—often things we at first find ugly or strange grow on us and we discover a depth and beauty that can be more profound than mere prettiness. The definition is complex and slippery and it changes over time. It’s not absolute and can’t be fixed. If that’s true, then no one can point to a thing or person and ever say unequivocally, “That’s beautiful.”

In a kind of defense of the notion of some kind of absolute beauty I’ve read that there are evolutionary and biological reasons that explain our criteria for ascribing physical beauty and attractiveness to people. People and animals have built-in visual preferences that we use to judge attractiveness and fitness. It’s said that symmetry, for example, is evidence of smooth physiological development—that symmetrical facial features are a sign of probable genetic health and fitness. The implication is that we may be biologically programmed to view certain things—in this case some other people—as beautiful. The accompanying implication is that we find them beautiful because they are suitable and desirable as mates. We call them beautiful but we’re thinking about something else.

I suspect that if that is true then it may extend to other aesthetic areas—landscapes and rooms, for example. Why not? Don’t some landscapes, with their unique light and setting, imply somewhat timeless criteria that would signal to our ancestors that this spot is a good place to nest, a good place to hunt, a good place to grow food, a good place to meet a mate?

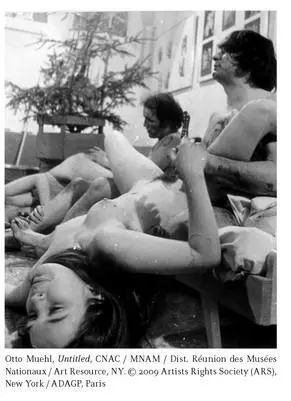

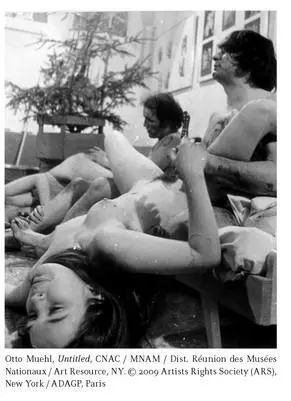

The talk turns to beauty’s opposite, in a sense—to the artists of the Vienna actionist movement of the 1960s, in particular Otto Muehl, who went to jail for allegedly having sex with everything and everybody in his commune—children included.

Here are the text/instructions for one of his “actions”: “I spread artificial honey on an old grandmother and then allow her to be attacked by 5 kg of flies that I had previously starved for 7 days in a box. I then kill the flies on her wrinkled skin with a fly-swatter.” Poor granny.

And another (from http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/38/muhl3.htm#12):The action is divided into various phases. First comes the still life. It begins very economically. You start with warm water on the bodies of the models, which runs—it doesn’t do any damage. Then comes oil, various soups with dumplings, meat and vegetables, perhaps even a bunch of grapes. Than [sic] comes color: ketchup, marmalade, red beet juice flows down. The skin is still visible. Then it gets going and the heavy artillery is brought out. I often made dough, which stretched down ponderously, or an egg, flour, or cabbage. Finally I poured on bed feathers. There was a certain structure there, how the materials were used one after the other. It was almost like cooking. I also once made, “The Breading of the Buttocks.” First milk, then flour, egg, and breadcrumbs. I didn’t take the entire body—only the ass, very provocative. The woman knelt in an armchair, her ass turned to the audience. First I sprayed the buttocks with milk. Then I dusted it with flour, as if breading a Wienerschnitzel. The flour stuck. Then I spread the egg yolk over that and at last the breadcrumbs. That looked really great!

And one for which he was arrested:The Christmas action “O Tannenbaum.” I lay naked in bed with a woman under a Christmas tree. I had hired a butcher. He killed a pig with a slaughtering-gun. He tore the heart out and hurled it onto us. The heart was still twitching. Blood spattered. Breathless silence reigned in the room.I slowly climbed up a ladder and urinated on the woman and the pig’s heart in the bed below. At that point, a women’s libber lost control. She rushed the ladder on which I stood and screamed: “You pig, you filthy swine!” I had 1 kg. of flour and dusted her down with it. A white fog. She screamed again, “You swine!” and she was gone, vanished. In the meantime, someone attempted to pelt me with potatoes. He came closer and closer and it was dangerous. I had another 1 kg. of flour and dashed it against him. The flour dusted his face and his suit. He stood there white as a snowman.

He said, “My life should be perfect, have direction, be an artwork.” Otto took this wish seriously, and soon he abandoned the arty actions and happenings created for a rarefied art-world audience and decided that they were actually a kind of therapy in themselves—they didn’t require the audience. So these activities could be beneficially incorporated and integrated into one’s life outside of the museum and gallery context. He would finally rip art out of its “frame,” as he had long dreamed.

“The action also has a frame, a stage, and people stand around. It is not serious. It is artificially produced. I want to rid myself of the word artificial.”

He founded a commune influenced by the psychosexual theories of Wilhelm Reich. It was a kind of action-group-psychoanalysis. Members were encouraged to act out—physically—their sexual and psychological issues. We can only imagine, based on Muehl’s earlier actions, what these might have been. Marriage in the commune was prohibited. There was a jazz band too, as Muehl was a big fan of Charlie Parker. Rumor is that the commune turned into his personal fiefdom, a real grotesque hippy artist cult nightmare.

Now, being somewhat rehabilitated in the perception of the art world, Muehl has, in recent years, been accorded big retrospectives in prestigious museums.

Stasiland

Berlin is lovely in the summer. In the morning I attempt to go for a ride in Tiergarten, the massive central park here, but Colin Powell, he of the Evil Empire (the Bush administration is still in power on this trip), is staying at the Intercontinental Hotel, so many of Berlin’s roads are closed and armed riot police are everywhere. They are bored, most of them, and they lounge around taking the sun, reading newspapers, and drinking coffees.

The presence in town of the Empire means I have to ride a very circuitous route wherever I venture near the central city—avoiding roadblocks and redirected traffic—but the weather is perfect, so it’s okay.

I’d heard that there is a Stasi museum in Berlin. I have recently read the book Stasiland , which details that life in which Big Brother encouraged everyone to spy on everyone else, so the museum sounds intriguing. It is some distance from the center of town—almost out in the suburbs—in a massive complex that served as the East German security services’ headquarters. It’s not listed in most of the museum guides—and Berlin has a lot of museums—so it requires a little bit of research to locate. I bike out, appropriately enough, along the amazing Karl-Marx-Allee, a sort of Soviet-inspired version of the Champs Élysées or Avenida 9 de Julio in Buenos Aires or maybe New York’s Park Avenue. But this boulevard is even wider and grander than many of those. The vaguely Moscow-style grand apartment buildings that line this boulevard outdo those in Moscow and rival the apartments on large avenues in other cities, except these are more orderly and repetitive, echoing each other, going on and on as far as one can see. The scale of both the street and these buildings is not quite human, and the images that come to mind and the accompanying sensations imply to me an idealistic utopian infinite heaven. Ideals and ideologies do not have boundaries, after all. This particular heaven, to me, is not like the typical ugly, bland modernist projects. That was a utopia of another sort. These have almost northern Italian detailing, and though they’re frightening in their somewhat inhuman scale and surreal repetition, they are far more appealing than typical North American housing projects or even a lot of Western modernist buildings where lack of decor came to be held up as a moral virtue. Here’s an infrared digital image:

Читать дальше