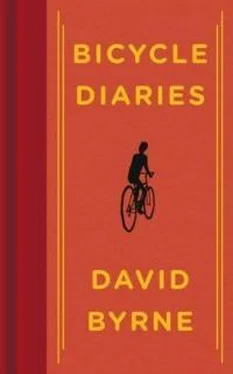

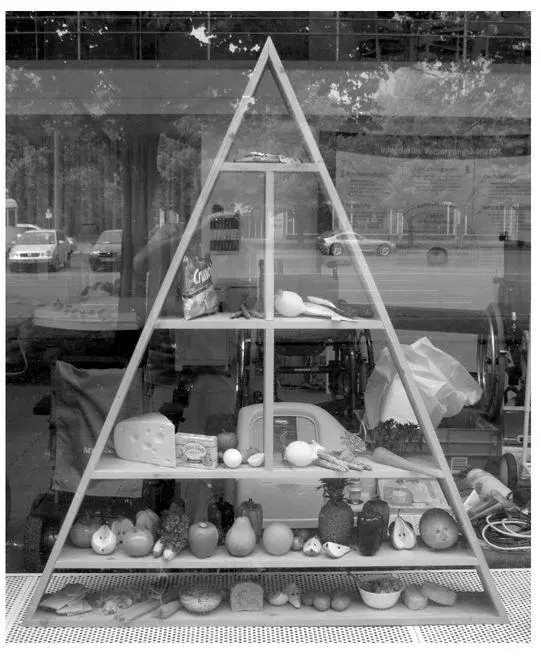

On one side of the boulevard the ground floors are sad and forlorn—former cinemas, hardware stores, and medical supply stores—most of which are either shut, decrepit, or reconfigured as DVD shops or similar fast-buck enterprises. The other side has charming outdoor cafés with tables arrayed in the shade of trees. The stores in general in this part of town seem to have lagged behind the gentrification that is now endemic in the center of town since the Wall came down. The luxury shops and goods that flooded into the former center of East Berlin haven’t gotten here yet. There is a window display in a medical supply shop that to me harks back to an earlier time:

A thing of beauty. What kind of thing, though? The basic food groups? Not exactly the basic food groups as we know them, but maybe that was the idea.

The hard times in some of the Eastern bloc Communist countries after World War II ensured that some of the existing architecture was left alone. Yes, it’s a cliché that neglect equals preservation, but there’s some truth there as well. At least the buildings that weren’t bombed in successive wars weren’t torn down and replaced with bland new edifices, housing projects, or highway overpasses. The Easties couldn’t afford it. Instead, the buildings were often given new purposes, as it was cheaper to do a slight refurbishment than to build a whole new structure. There was little money for wholesale urban redevelopment here, unlike in many Western European and North American cities, and besides, the Allied bombing had cleared much of the city anyway. While Robert Moses had to raze whole neighborhoods in New York to make space for his highways and housing developments, here the demolition part of the job had already been accomplished. Some buildings that in the West would have been torn down were left standing as they were the few that remained, and those are now extremely desirable. One blatant exception is the former Communist Party headquarters on Alexanderplatz in the former East Berlin, a giant postwar modernist monument, copper-mirrored and toxic—both psychologically and chemically—which is being slowly and very carefully dismantled due to the amount of asbestos inside. The removal of this psychic eyesore is controversial, as it symbolically erases a prominent reminder of the former regime and of the country’s recent history—just as the Nazis took over and repurposed formerly Jewish-owned offices and buildings and then the Communists later reworked and renamed the Nazi buildings to their own ends. Eliminating this eyesore is wiping away part of the collective memory.

I passed through and worked in West Berlin fairly often in the ’80s, when the Wall was still up. West Berlin then was an artificially pumped-up, arty capitalist showcase, the better to show those commies on the other side of the fence what high life and culture they were missing. East Berlin was full of incredible historical buildings and shabby apartments, and there were no amenities. It really was gray and depressing—at least to a visitor. And it smelled—many houses and businesses were heated by coal fires, a smell I recognized, and loved, from visiting my grandma in Glasgow as a child. Even the sky seemed grayer to Western visitors then.

I suspect that many of the folks who lived in the East felt otherwise and may have viewed the half of the city on the Western side as a decadent cesspool of junkies and hookers (which it partly was) while they alone were maintaining the traditionally high German intellectual, cultural, and moral values and standards. Someone, they might have reasoned, had to preserve civilization while the Yankees turned West Berlin into a soldier’s playground and a haven for crazy artists, playwrights, drug addicts, and musicians of questionable talent.

In West Berlin at that time the young Germans who didn’t mind living inside a walled island were compensated—they could escape compulsory military service, rents were relatively cheap, and parking laws were almost nonexistent. (Cars would park on the sidewalks, at any angle, and never get towed.) Kreuz berg, the Lower East Side of West Berlin, was one of the most decadent low-life places I’ve ever seen. Lots of black leather, heroin, and late-night punk clubs—a sort of government-sponsored bohemian world just out of reach, but significantly visible to the Easties just over the Wall. The rest of luxurious Western decadence—the plentiful food, crazy fashions, and expensive cars—the Easties could see on bootleg films and TV, and they could probably smell wafting across no-man’s-land the curry wursts and kebabs that fueled the nightlife just across the Wall.

After the Wall came down all that changed. There was no further need to artificially entice people to live in an isolated island city anymore. Now the decadence here is of another sort, and it has migrated to various neighborhoods in the center of the former East. Friedrichstrasse and the surrounding boulevards are filled with luxury-goods boutiques, designer labels, and swanky hotels. There was a brief time right after the Wall came down when the historic buildings of Mitte were selling for peanuts, and many of them quickly became squats and cheap housing for artists, but that was a relatively short-lived period. Now there are a few coffee shops and some graffiti remaining as reminders of those post-Wall days, but the fancy-goods stores and developers are moving in fast and the rents are going up. More mentally disrupting, for me at least, is that the entire center of town has moved. When the Wall was up, what we in the West considered the center of West Berlin was somewhere around the tower of the bombed Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche, and Kurfürstendamm and Kantstrasse radiated outward, but now the center has shifted back to more or less where it was before, pre-cold war—to Friedrichstrasse, Alexanderplatz, and Potsdamer Platz. It’s as if my memory were playing tricks on me.

Big old Karl-Marx-Allee has yet to catch the wave of gentrification, though the apartment buildings have been cleaned up and I hear the former apartments of party members and Stasi higher-ups are lovely. So, this route is a fitting prelude to the Stasi Museum visit.

Stasiland, the book by Anna Funder, an Australian journalist stationed in the former East Germany, investigates personal stories involving that notorious state security agency. Funder’s perceptions are wonderful. She spots the bizarre and oppressive not only in the detaining and spying on citizens and the unexplained deaths, but also in things like a weird sexless popular dance (the Lipsi) that the government attempted to insert into popular culture as a kind of immunization against Elvis’s rock-and-roll gyrations.

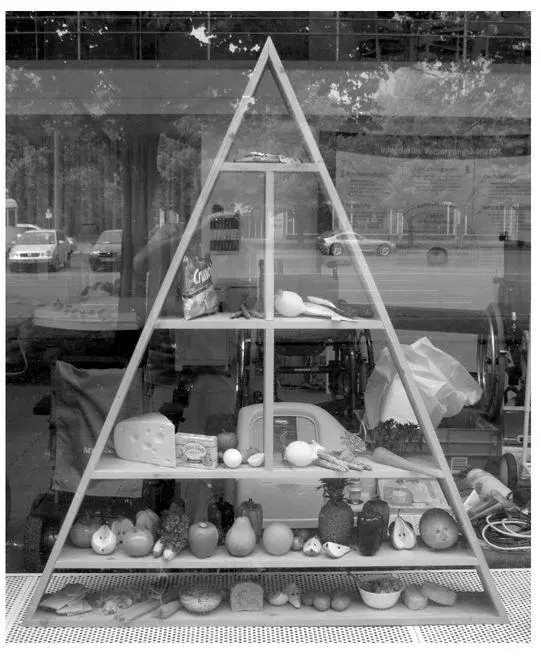

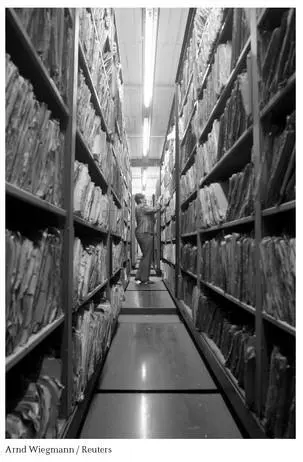

The Stasi kept massive “files” of all types: Some consisted of jars of smells of suspected subversives—jars that were filled with scraps of clothing, or preferably underwear, secretly procured from some poor soul suspected of a lack of patriotism. In some cases if actual clothing belonging to the suspect could not be found then an agent would surreptitiously wipe where that suspect had been seated and then quickly preserve the rag, labeling it by name of suspect and how long he or she had been seated on said chair. These rags were filed away just in case that person should disappear, and then at some future date a dog could sniff the rag and presumably discover the culprit’s hiding place.

Читать дальше