Belly Dance Party

Upon returning to the hotel, I rendezvous with a group of Turkish expatriates (who now live now in Belgium, New Jersey, and Chicago) and upon the arrival of a Kazakh gentleman, we depart for the Sulukule neighborhood to eat, drink, and be entertained by low-rent belly dancers. This gypsy neighborhood, a thousand years old, is almost all run-down houses and tea shops filled with people hanging out on the semipaved streets in the cold night air. Sadly, the whole neighborhood is threatened with demolition now, as it’s coveted by real-estate developers.

Our friend from Kazakhstan knows which house we’re heading for, so we ignore the kids who swarm over the car urging us to stop at their families’ establishments and we proceed to “Chez Moi.” We’re met by more Kazakhs—bankers, they claim, although one wonders exactly what sort of “banking” these fellows do—and then a group of bleach-blond babes with rouged cheeks dressed in bulky sweaters. The house mother, a short woman in a house dress (is she pregnant?), leads us to “our” room, upstairs, where we will be entertained and, we have been forewarned, fleeced.

This is the polar opposite of Sakip Sabanci’s mansion, in the extreme. As the room is stone cold, “Mom” carries in a bucket of glowing coals from outside and plunks it down in the middle of the linoleum floor, which is pretty ripped up in spots. Our Kazakh friend begins to negotiate while we get settled. The room is almost completely bare, except for the mismatched chairs that line the walls. A kid brings in a kind of folding card table. Four musicians (two percussionists, a tambourist, and a man with a Turkish banjo) seat themselves opposite us and begin to tune up.

The dancers, still in their winter sweaters, enter briefly and then leave. Mom takes drink orders—beer for the expats and me, roki for the Turks, and vodka for the Kazakhs. A Kurdish gentleman, who might be part of our party, sits near the musicians. He doesn’t drink.

The musicians start to wail. They sound great, full of vigor and emotion that explodes in sudden bursts of intense and beautiful sadness. The sadness of the world is in this music. I don’t care if they’re just playing for us to make a quick buck; it’s deeply moving anyway. I’m transported. A kid circulates and takes “donations.” Cheese, grated carrots, and pistachios appear and eventually even a dancer, who makes the rounds before she starts asking for more donations (small bills seem to do). She takes off her sweater and plops it on a chair, revealing not a costume, but her bra and a pair of tights, rolled down just enough to reveal the arches of the top of her panties. She begins to dance. Not belly dancing really, but whatever it is, it’s got some spirit. Everyone, whether from the cold, the drink, the music, or the whole situation, is in great spirits, laughing and toasting one another.

The dancer makes the rounds again, and bills are stuffed in her bra this time. Occasionally she does a sort of very basic lap dance. She sits on someone’s lap (male or female, it doesn’t seem to make a difference) and bounces up and down. It’s more funny than it is sexy. It’s all pretty tame, and it’s not really belly dancing, but everyone’s having a great time. Except for the man on my left, who twirls beads all night and consistently asks the girls to pass him by, most of us get up and dance at one point with the girls or with each other. Everyone laughs, fills one another’s glasses, sings, shouts, and pastes dirty old bills on skin. The Kazakhs are getting pretty sloshed on their vodka, but nothing untoward ever happens. And, as the dancers don’t have the requisite tummies for belly dancing, a few of the women pull off the shirts of the men, whose bellies are more than ample enough for shaking.

At one point there’s a commotion outside and we discover a local TV team, led by a famous local talk show host (who resembles Fidel Castro a little—he’s bearded and wearing green fatigues). The Turkish elections are about one week off, and he’s polling the citizens of this poor neighborhood about their situation. He’s surrounded by belly dancers on break, street kids, and the owners of the house.

I’m told that the outcome of this election, like many of the elections coming up in central Asia and in the former Russian republics, will demonstrate to what extent a sizable chunk of these populations want to return to a more stable world, whether it be based on the Communist religion or the fundamentalist sort. It is said that the fundamentalists here are very well organized, as opposed to the young secular moderns, who are largely apathetic and couldn’t care less about politics. The religious party, it is rumored, is even flying in votes from the Turkish communities in Germany and Austria. They pay for the round-trip airfare, it is said, in order to guarantee another vote from the expats. Naturally, all this fervor is stronger in the eastern part of the country, far away from Istanbul, where a war with the Kurds has also been going on for years.

There is a big gap between rich and poor here, just as there is in the United States, although here in Istanbul one doesn’t see, as one does in New York and other cities, the really wretched poor discarded by society. This country is truly on the border between East and West, and the conflict between westernization—the chaos of democratic liberties and heartless capitalism—and a way of life that surrenders to the righteous and sheltering arms of God and tradition may play itself out here.

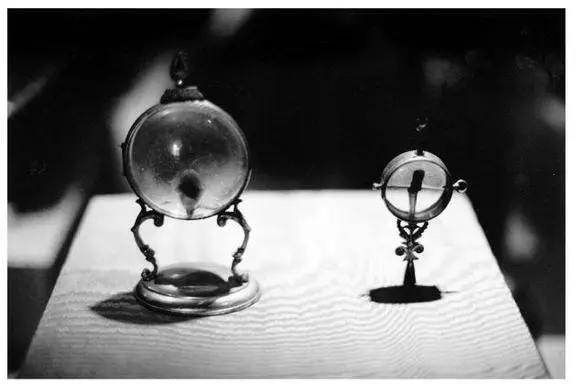

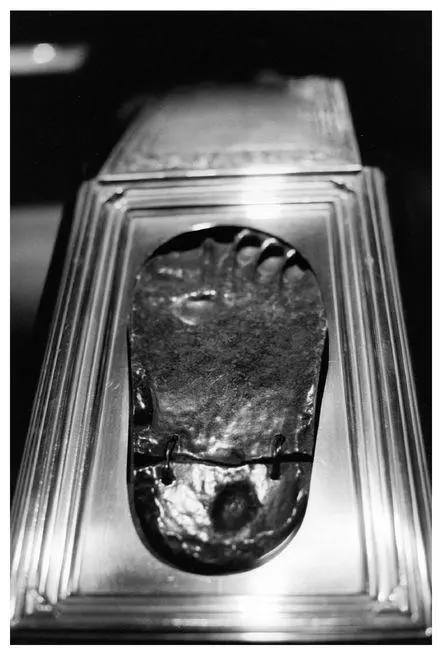

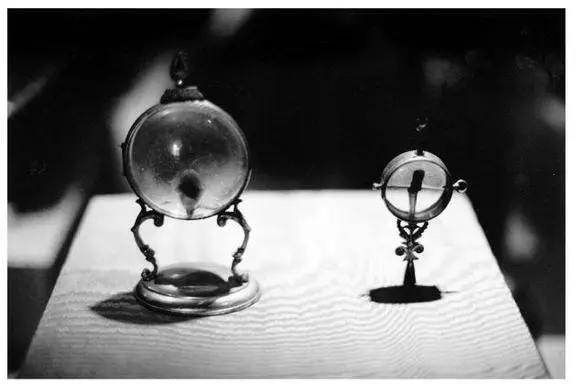

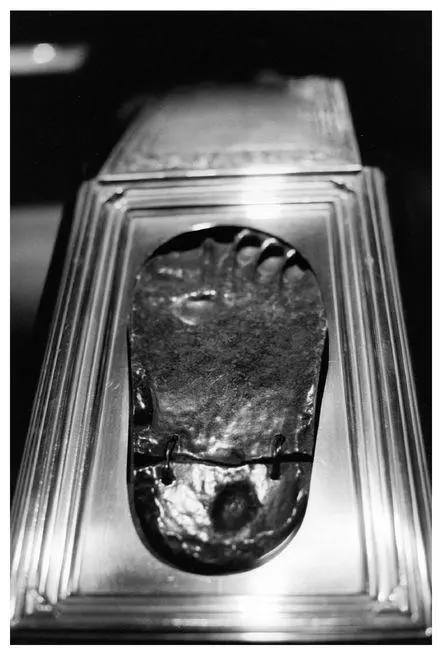

The next day I ride over to the beautiful Topkapi Palace, a tourist attraction, to see its harem museum. While the proportions and scrollwork of the interior of the palace are incredible, I am more taken by the displays of religious relics. In other places, in other countries, these would be displayed in a cathedral or in a shrine of some sort—they are the holy of holies, after all—but here they are all grouped together in a museum room. A hair from the prophet, the sandal print of Muham mad, the arm bone of St. John the Baptist, and more skulls and bones are all shown in this way as if to prove how successfully Atatürk has turned the country into a secular nation.

I bike back across the Horn, over the bridge to the hotel, and in the evening I have dinner with the local concert promoter and a few of her assistants. Alev, the promoter, is a forthright, energetic thing, and her assistant Daniel (I’m sure that’s not his real name; I suspect it’s been anglicized), who picked me up at the airport, is a slightly effeminate immigrant from Kazakhstan arrived here via Moscow. In other words, he hasn’t yet acquired the requisite mustache upon entry into Turkey, which I imagine makes him appear slightly less manly than the traditional men here. The ubiquitous mustaches were commented on by Alev and her staff as being indicative of a certain type of Anatolian. This view of facial hair marks my shaved friends as being somewhat more cosmopolitan, and I guess slightly more alienated—their view of mustaches might be comparable to my view of mullets, I would imagine.

Hairs of the prophet, Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, 1992.

Footprint of the prophet, Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, 1992.

In the five years of her company’s existence Alev’s main focus has been promoting raves and dance events (dance music events meaning house and techno parties, not ballet). The festival of which I am a part is to take place on a beach site on the Black Sea, about an hour and a half’s drive from here. They call it the Alternatif Festival. There is to be a big tent, toilet facilities, all the usual Euro music festival structures, and the usual set of sponsors—a jeans company, Carlsberg beer, a radio station, and CNBC.

Читать дальше