A crane fell here in Manhattan today as I type this. It killed four by last count and smashed a neighboring building. Another building went down two weeks ago, and the week before that part of a Trump building collapsed and a man was beheaded.

In the guise of uplift and progress, these buildings actually dehumanize people when they don’t kill them outright. Although they are all made of identical materials—reinforced concrete, glass, and steel—they don’t soar and swoop like the interstate highways, dams, and bridges made of the same materials. The graceful arcs of interchanges on the expressways and autobahns are not mirrored in these condo blocks. Neither are they meant to last like those structures. The future is here, in spirit, for an instant—but it will disappear, it will crumble, before our very eyes.

So instead of a small number of really impressive “monuments” such as those that survive from the disdained historical past, our century will leave, across the planet, a sprinkling of almost identical structures. It is, in a way, one vast global conceptual monument, whose parts and pieces are spread across the world’s cities and suburbs. One city, in many locations.

They’re doing it in New York right now. All over town almost identical concrete and glass buildings are rising. Many are going up so quickly that one wonders if the speed of construction isn’t just a way to get them up before anyone can object. Now, with the credit/economic disaster in progress, the heat is truly on to spend any previously allocated money. Some towers have the names of famous architects attached, others do not. Visually it’s often hard to tell them apart—they are all, ultimately, designed by the developers, while the starchitect is simply another kind of logo that can be applied in an attempt to distinguish one building from the other.

On a previous trip to Istanbul I had been invited by a group called the Dream Design Factory to do a public art installation during the Istanbul Biennial. The biennial is fantastic. Not all of the art is great and most of the artists are new to me—many hail from Turkey, Syria, Greece, Egypt, India, Iran. Not very many artists in the big Chelsea galleries are from those places, not yet. The exhibit locations are in wonderful old structures scattered around town—factories, warehouses, and customs offices, even in the Roman cistern that lies under part of the historic district.

My piece won’t be in one of those places. Instead, I’ll be installing in an as-yet-unrented space in a modern shopping center that is not quite in the center of town. At least it will have lots of foot traffic. I’m a little disappointed about it not being centrally located, but it’s great to be here. My show will be some bus-shelter-sized lightboxes with computer-manipulated images of personal weapons and money. They are meant to look like glitzy contemporary ads, so the shopping mall location might not be so bad after all. I stay at the Pera Palas Hotel, a slightly run-down joint that was once, in the days of the Orient Express, the height of elegance. Hemingway, Garbo, Hitchcock, and King Edward III stayed here, as did spies such as Mata Hari and Kim Philby. Atatürk stayed here too, and his room, number 101, is kept as a museum.

Pera Palas Hotel elevator, Istanbul, 1994.

Sakip Sabanci

The next day the Dream Design team meets me at the hotel and we drive along the Bosphorus. The team is led by Arhan, who looks like a Turkish Tin Tin, with one shock of hair sticking up in front. The Dream Design Factory does graphic design as well as events, promotions, fashion shows, and raves. We are also joined by Esra, a young woman who seems to have arranged today’s field trip, and Arhan’s friend Saba, an elderly Turkish artist who now lives on the island of Elba, off the coast of Italy. It’s raining, traffic is snarled as usual, and I’ve seen this route before, on my bike, so I drift off to sleep in the backseat of the car. I can hear Saba, a bit of a Marxist, announce on seeing the spate of new billboards that have sprung up: “Who owns my vision? Who owns what I see?”

The mix of Esra, a young and cosmopolitan woman, Saba, the leftist artist, and Arhan, the designer-entrepeneur-raver makes for an interesting crew.

After a while I am awoken by Esra—“David, we’re here”—to the sight of a huge white gate, which opens in front of the car. At the top of the driveway is a giant mansion overlooking the Bosphorus. On the left is a slightly smaller, more modern house on the same property. I head for the big house, still half asleep. “No, not that one, the other one,” someone shouts. Passing by a massive picture window, I wave at a woman sitting on a sofa with a child in the tasteful contemporary interior.

The woman meets us at the door. Strangely, she isn’t much taller than she was when we saw her sitting on the sofa—her legs are shrunken and twisted by cerebral palsy. We are soon joined by her sister and offered drinks, which a butler in a double-breasted suit hurries off to fetch. Small talk. Apologies for not making it to the opening of my exhibition here. A silent woman who is not introduced feeds a child. I walk around examining the paintings in elaborate gold frames on the walls.

Esra announces that we can see Sakip’s father’s collection if we like. I don’t know what kind of collection she’s referring to, but I’m game. We head for the big mansion after a cell phone call to alert the staff over there. The sister, nanny, and child stay behind. Sakip Sabanci was one of Turkey’s most successful businessmen. He’s also known for his philanthropy—he built hospitals and founded a university.

We’re met by the same butler, who must have slipped out ahead of us. The house is a museum—in the Victorian sense. The ground floor is filled floor to ceiling with paintings, vases, period furniture, statues, and glass cases filled with silver objects. As we enter a room on the right, an announcement is made—“This is the blue room”—nothing more. Any questions about individual paintings are answered by the butler. We move through room after room. Saba, being of a certain age, recognizes the work of some fellow expatriate Turkish painters who relocated to Paris. Most of the other paintings are “Orientalist” in style, Ottoman-era romantic depictions of street life in Istanbul, although there are a few Russian romantic landscapes as well—sunset over the Neva and views of St. Petersburg.

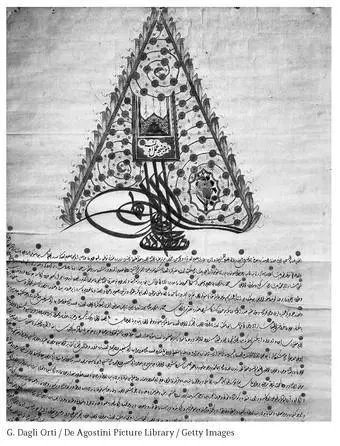

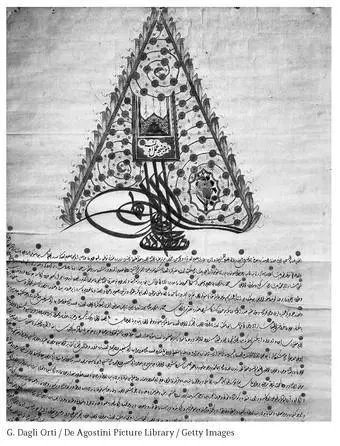

The first floor, upstairs, is reserved for the amazing calligraphy collection. Ottoman-era pronouncements on law and policy, letters, and Qur’ans, of course, open to golden pages with elaborately embellished passages from the Book of Books. It’s all beautiful. Interestingly, the Ottoman and Asian calligraphy pieces are much more impressive to our contemporary (Western) sensibilities than the more typically Western paintings and sculpture on the floor below. The Western and especially the Orientalist paintings to us smack of a dated colonial romantic vision of the East that some of us would like to believe is in the past. Those paintings remind us a little too clearly of our prejudices and smugness. Whereas these calligraphic works seem, for the moment at least, perfectly in synch with contemporary Western sensibilities—text as art, the word as thought made beautifully tangible—even if they might have been oceans apart from those abstract and formal ideas at the time when they were made.

Читать дальше