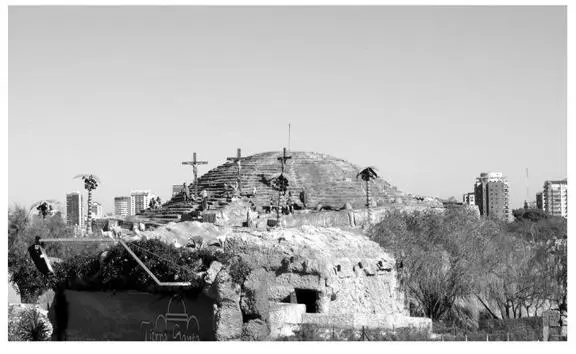

Fishermen lean on the railing. There are kiosks at regular intervals that grill meats for truck drivers and others who want a quick lunch. Bags of charcoal piled by the sides of the kiosks will supply the heat to grill blood sausages, steaks, hamburgers, and various other cuts of the legendary Argentine flesh that sizzles during the early part of the day in anticipation of the lunch crowd. Many of the kiosks advertise choripan , a conjunction of chorizo (sausage) and pan (bread). There’s another offering called vaciopan , which literally means empty sandwich, but it also is a cut off the cow. This is not a place for vegetarians.

The slang here, called lunfardo, is many-layered and inventive. There’s even a genre of slang called vesre when you reverse the syllables— vesre is reves (reverse) with the syllables reversed. Tango becomes gotán and café con leche becomes feca con chele . Sometimes this is compounded and complicated even further when a euphemism for something—a word for marijuana or one’s wife—is pronounced backward, adding yet another layer of obscurity to a slang that already approaches a separate language.

Bobo

My lovely hotel in the Palermo district is named after the book Bobos in Paradise, a humorous essay by the North American writer David Brooks about the gentrification and commercialization of bohemian culture, which makes it a confusing name for this hotel, as it and this neighborhood are prime examples of that process. The word also means “fool” in many languages. It is as if the Tribeca Grand had a name that poked fun at the fact that it’s located in a gentrified, arty neighborhood. This hotel is located on Guatemala Street, between Jorge Luis Borges and Thames streets—the street names alone say a lot about the cultural makeup of this town, with its mixture of Latin American and European references. It reminds me of how street and town names not only commemorate dates and well-loved (by some) politicians (LaGuardia Place and the FDR drive here in New York, 9 de Julio and Avenida de Mayo here) but also express a conscious mythmaking and cultural longing—a longing for connection, historical continuity, and status. The hundreds of little U.S. towns named Paris or Madrid, the cluster of historical Greek towns in upstate New York, the New London, New Jersey, and New Orleans, Venice Boulevard—how a people see themselves, or how previous generations saw themselves, is embedded in these names. At a glance one can sense how the past is perceived—what people wish their history to be and what is intentionally omitted.

Mauro, who plays percussion with me, said, with a disappointed tone, that he felt Santiago, where we were earlier on this trip, was very much an “American” city (meaning North American). I can see what he means: it’s pretty, it’s clean, and there are lots and lots of glass office buildings and little of the messy character, charm, or funk of Mauro’s native Brazil. Mauro pointed out that Chile was one of the only countries that didn’t have slavery. What he might have been implying was that it was the Africans who give South American culture much of its character. Being Brazilian, he would say that. Certainly much of the unique music on this continent, and subsequently of many others these days, is a hybrid of European, indigenous, and African styles. It has been argued that even tango has some African in its family tree. Though musical roots and influences are not so hard to hear, at least to me, cultural influences extend in deeper and subtler ways—in grammar and syntax, in humor, in attitudes toward the body and sex—that are harder to tease apart from every other influence. The past is part of the weave, but often we see mainly the overall surface pattern.

Last night a small group of us were joined at dinner by Ignacio Varchausky from the local tango Orquesta El Arranque. He mentioned that numerous groups these days are trying the tango/ electronic fusion, but to his mind none of them have succeeded yet—not that he doesn’t think it’s a worthwhile goal. Unlike lots of tangueros here, who tend to be fairly protective and conservative, he and the other members of El Arranque are open to col laborations and to new approaches, both from that music’s past and from other foreign styles. Lately, the band members have unearthed old (1940s) handwritten tango orchestra arrangements, and some of them are surprisingly radical, he says. The orchestrations became more smoothed out since then, more conservative, and these older, wilder approaches were often swept under history’s rug and forgotten. They’re in the middle of completing a CD on which older tango masters, those who are still living, join them and play with the younger guys. He says this is unusual because tango is not a very collaborative or open scene.

Later that night I run into Nito, a member of the local band Los Autenticos Decadentes. They are a large band that came up in the ’80s along with Los Fabulosos Cadillacs. (As one might imagine, the Cadillacs name is meant both ironically and sincerely; here one can love North American pop culture and distance oneself from it at the same time.) Both bands were initially inspired by the Two Tone bands in the UK and the ska scene there (Madness, the Specials, Selector), as were No Doubt and many other bands around the world. Those short-lived UK bands have more bastard children than is often acknowledged. Both of these Argentine bands rapidly evolved and began to incorporate local influences. Los Decadentes fell in love with regional popular styles—working-class dance music and murga , a kind of carnival music—to which they added contemporary lyrics, while Los Fabulosos Cadillacs incorporated more Afro Uruguayan and tango sounds and rhythms.

Nito and I had crossed paths years ago in New York City when Los Decadentes performed at a disco and I lent them an accordion. Back then the band was viewed by locals here in Buenos Aires as a kind of theatrical comedy band—a bunch of rowdy goofballs, which they more or less were at first. Musically, they weren’t taken seriously, though soon enough they learned to play, stay in tune, and write amazingly catchy songs in a variety of rootsy and popular genres—if you include disco anthems as roots music, and I do, since disco pop is heard in bars everywhere alongside rancheras and cumbias . They soon had hits and became fairly popular.

I ran into Nito in Mexico City after a show I did there, and he amazed the Mexicans with his knowledge of narco corridos, the ballads sung in the north of that country that glamorize the exploits of drug dealers and traffickers. One could draw a parallel in contemporary rap lyrics with, for example, Ghostface Kil lah’s song “Kilo,” but these Mexican songs are performed with accordions and guitars. Nito knew the words to all of them. Now, here in BA, he’s handed me a pile of CDs of Argentine and Paraguayan cumbia bands. I didn’t know such bands existed in those countries (those rhythms are usually identified with Colombia or Mexico, not with these countries farther south). There’s even a bachata band here, something I thought only existed on the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo. He says Paraguay is the Jamaica of South America, though what he means by that is slightly unclear. He’s not referring to the dope. I think he believes they’ve evolved an original slant on music and have a voracious appetite for whatever they hear, from wherever. Their own popular music incorporates and absorbs a lot of music they hear, but they process it and give it their own twist, and it’s hugely influential—at a grassroots level. The music these Paraguayan bands play is not sophisticated in the accepted sense. It’s trashy music for the two D’s—dancing and drinking—but as often happens these outsiders—the musicians from Buenos Aires—are recuperating this low-class music and re-presenting it to a new audience, the way the British appropriated U.S. blues and Detroit techno and sold it back to the United States.

Читать дальше