There were disappointments, too. A Dublin sailmaker who had, three months before, agreed to send a man down to measure the boat for its very important spray hood now doubled his price in a transparent effort to get out of doing the job. He succeeded. Then a west coast sailmaker agreed to do the job and never showed up for the appointment, after keeping us waiting an entire afternoon. He didn’t even bother to phone to say he couldn’t make it. John McWilliam, from the heights of the international racing sailmaker, would not stoop to such mundane work, either, but at least he had made it clear months before that he wouldn’t touch the job with a fork, and he didn’t waste my time the way the others had. Before the summer was over, I would suffer from the lack of that spray hood.

I drove up to Tralee and spent an intensive two days with Len Breewood, studying celestial navigation and trying to cram two weekends into one. Len very kindly made me a gift of a light meon anchor which he had made himself. I had been unable to find one like it in Ireland.

Then I drove to Galway and spent an enlightening morning learning how to make a diesel engine behave itself. I had never seen one up close before, but even I understood and came away with a large donation of expensive engine spares. (A few days later, an extremely heavy parcel arrived in the post. Hydromarine had sent me a spare propeller, a very expensive chunk of brass!)

Back in Cork, visible progress was being made on the boat. The keel had been fitted, as had the stainless-steel brackets for the self-steering, and I watched as the deck was dropped onto the hull and fastened in place. At last, it looked like a boat!

Acceptances and regrets began to come in for the launching. Sadly, Ann would be working (she designs sets and costumes for films) and could not be in Cork. But other people were coming from all over the country.

At McWilliam Sailmakers, another last-minute flap. I had designed a “Betsy Ross” (the lady who designed and sewed the first American flag) spinnaker, in honor of the 1976 Bicentennial Celebrations in the States, and this called for a circle of thirteen stars on a field of blue. The problem was that John had, instead of making five-pointed American stars, made six-pointed Israeli stars. Wrong celebration. I had to spend an hour soothing him and telling him how easy it was to make five-pointed stars, and he still charged me three quid apiece for them.

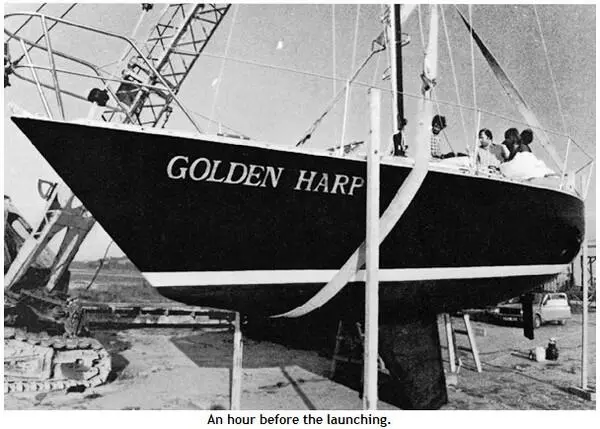

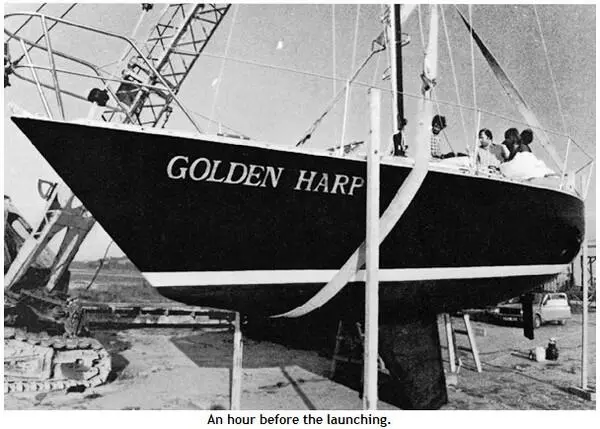

Launch day dawned. Nick and I were at the yard early to find the boat now hauled out onto the quay. The gathering for the launching was scheduled for eight in the evening, and the boat would be open to visitors for an hour before launching at nine, on the high tide.

About eight-thirty, people began to arrive and, suddenly, it all came together. By a quarter-to-nine Golden Harp bore every resemblance to a finished boat, her loose wires tucked away and the floorboards and dining table suddenly in place. She was nothing if not a fine actress.

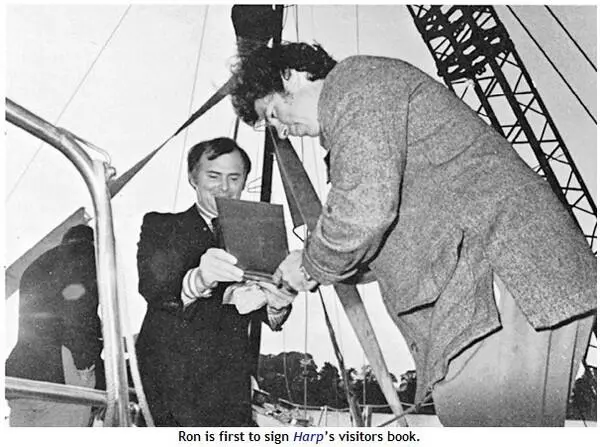

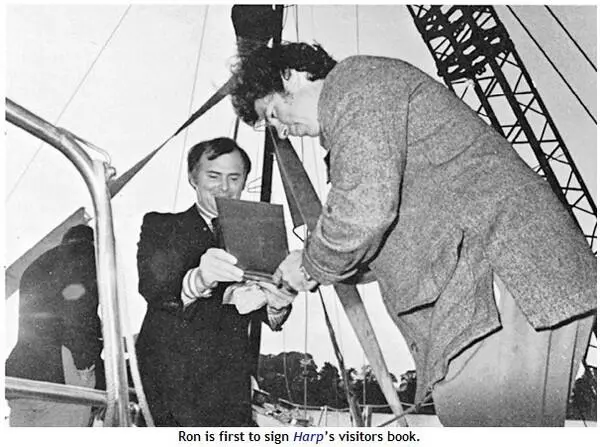

John Smullen, my insurance agent, arrived from Dublin with a lovely young lady and the gift from himself and Alec Hinson of a handsome visitors book, embossed with the yacht’s name. It was a psychic thing, for I had not been able to find one in Cork.

Rapidly, its pages began to fill. Ron Holland and John McWilliam were the first signators; George Kennefick, admiral, and Raymound Fielding and Harry Deane, vice-admiral and secretary, respectively, represented the Royal Cork Yacht Club, now Harp ’s home club; Ferdia O’Riordan and Michael Healy turned up to represent the Galway club, while Harry McMahon, though we did not know it at the time, was at Dublin Airport, having come from a medical conference in Edinburgh, trying to persuade Hertz to hire him a car without a driver’s license, which he had forgotten; Worth and Pasha Newenham came, so did Len and Margaret Breewood; friends from all over were suddenly there, admiring my boat. Nick had miraculously got the tape player going, and the music added to the festivities. Tom Barker from the Cork Examiner was there, and although RTE had had to divert its one Cork camera to a fire, or something, Irish radio was represented in person of Donna O’Sullivan, a redhead of whom I would see more.

Now all my anger and frustration vanished under a wave of euphoria. It was just as though the boat was actually finished. This moment, which I had dreamed about, but of which I had begun to despair, had finally come. It was all exactly like a real boat launching.

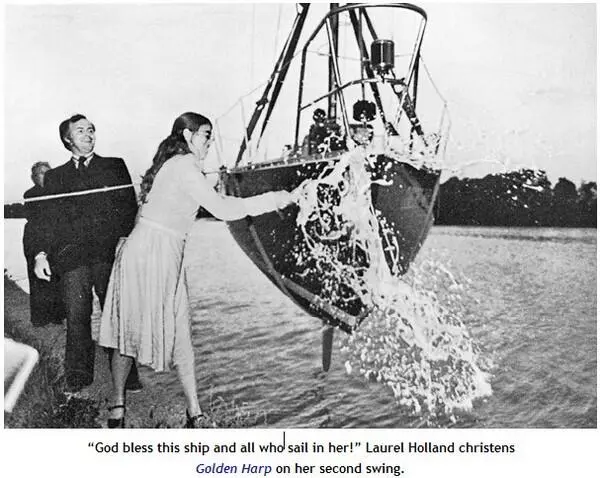

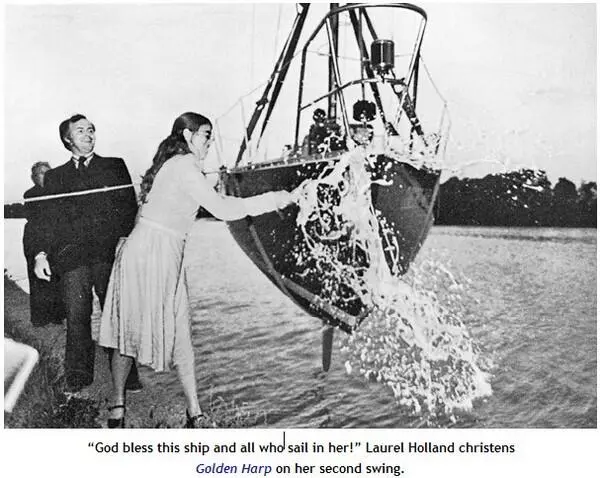

Finally, George mounted the crane, swung the yacht over the quayside, where she paused, her decks level with the stone. Barry Burke, who was not able to be present for the launching, had provided a bottle of champagne, cleverly scored several times so that it would break at the first blow. It is supposed to be terribly bad luck if the bottle doesn’t break the first time. Laurel Holland, terribly conscious of her responsibility, said, “I christen this ship Golden Harp. God bless her and all who sail in her!” and swung mightily at the bow, missing the boat completely. She hadn’t actually touched the boat, though, so no harm done. On her next swing the bottle smashed just the way champagne bottles are supposed to at yacht launchings, and Golden Harp dropped into the Douglas River with a fat splash.

It was all so perfect: the water of the river turned to shimmering gold by a huge setting sun, the crowd gathered to wish the boat well, the lovely weather. I made a short speech, thanking Ron and other people who had contributed to the effort thus far, and we adjourned to the upper deck of the Royal Cork for a bit of champagne.

Toward the end of the evening George Kennefick made a few kind remarks, and in my response I was able to thank George Bush, whom I had stupidly forgotten to thank at the launching. George had been in charge of the most difficult of all the work, the modifications, and his work would prove to have been done well.

I hit the bed that night like a felled tree. I don’t think I’ve ever had a better evening.

The following morning, Nick and I drove to the yard with as much equipment as we could manage, and we began to load the boat. George persuaded me to wait for the afternoon tide, to give him time to do a few more things, and I agreed.

As we were preparing to cast off and the last workman was hastily gathering his tools to avoid a trip down Cork Harbor, I glanced into the shallow bilges and noticed water there. “Where did that come from?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he replied, shaking his head. “I’ve mopped her out every morning since she was launched, and there’s still water coming in.”

Golden Harp, four days after her launching, was leaking.

13

The race before the Race

The next three weeks were a whirling potpourri of rage, outrage, relief, elation, depression, and exhaustion.

Ron came down to Drake’s Pool and shouted from shore that he was leaving for Norway the following morning to compete in the World Three-quarter-ton Championships in his design, the Nicholson 33, Golden Delicious. The delays in finishing the boat had robbed me of one of the most important elements of my plan, the presence and advice of Ron, helping me to learn to understand and sail the yacht. Before we sailed for Portsmouth and the MOCRA Azores Race, he would be able to spend only three hours on the boat.

Читать дальше