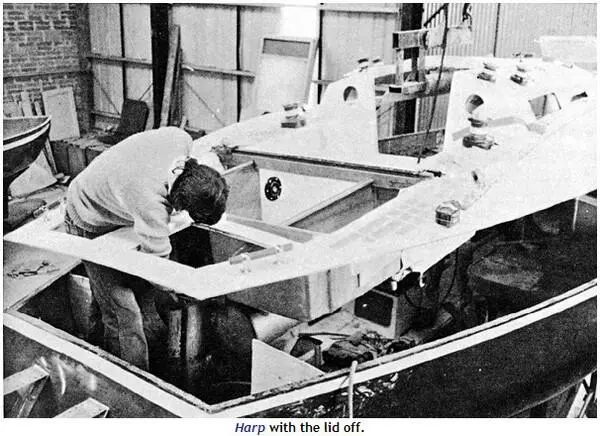

By Tuesday, back in Cork, my boat was finally molded but not yet out of the mold. I had signed on for a week’s cruise on Creidne, the Irish Training Ship, the following week, and before I left, Ron and I went down and worked out the deck layout and gave the instructions to the fitting-out foreman. Basically, all the winches and controls were grouped as closely to the cockpit as possible, so that they could be reached and managed by one man. This differed from the standard deck layout, where halyard winches are operated by crew on deck rather than one man in the cockpit (see diagrams). We also had a long talk with the joinery foreman about changes to the interior layout, mostly the addition of extra stowage place wherever possible. That done, I drove to Dublin and joined Creidne in Dun Laoghaire.

Aboard Creidne, which is a fifty-foot Bermudan cutter, purchased by the Irish government as a temporary training ship during the planning and building of a new eighty-foot brigantine sail trainer, I was delighted to find Ian Mitchell, an old friend from the Mirror racing circuit. Eric Healy, a toothy, tubby, chatty gentleman with vast experience in sailing vessels all over the world, is Creidne ’s permanent skipper, and he assigned Ian and me as duty skippers for our planned voyage to Holyhead, across the Irish Sea, in Wales.

First, though, we did a few drills in Dun Laoghaire Harbor, picking up moorings under sail, man-overboard drills, and power handling. Then, up at an early hour for the passage to Holyhead. We had a pleasant and uneventful crossing in lightish winds, and Ian and I both learned the importance of judging tidal streams, for Holyhead turned up on the port instead of the starboard bow, where it should have been.

The trip back on the following evening was more exciting, with the wind blowing Force five and six. Several of our crew had tanked up on beer the night before and, in the short, steep seas we now encountered, they paid the price. Both our watches were shorthanded as a result, and we got little sleep. We underestimated the tide again, and had to put in a half-hour tack to clear the Kish light, just outside Dublin Bay, all the while dodging the Dublin — Liverpool car ferry, which seemed awesomely large from the deck of even a fifty-footer.

Back in Dun Laoghaire we changed crews for the second cruise of the week, only Ian Mitchell and I remaining from the first group. We sailed down to Wicklow, then Arklow, then back to Dun Laoghaire. The week had been especially valuable experience for me, doing everything from foredeck work to cooking to skippering, and giving me experience with the cutter rig, which has two foresails. At Dun Laoghaire, Captain Healy let me bring Creidne alongside under power, which happened without incident but perhaps a bit slowly. In his evaluation of my week, Captain Healy mentioned that I should be more patient with the crew when skippering, and that I needed more experience under power. I didn’t tell him I had never handled a boat under power before.

Archie O’Leary had asked me to come along on the delivery of Irish Mist to Lymington the following weekend, and I busied myself with the final details of rounding up equipment for my boat. Manufacturers can be remarkably slow sending equipment, even when it has been paid for in advance, and I was constantly having to chase orders to see that everything arrived in time for the launching.

Quotes for insurance came in, and I chose the one from Hinson & Company in Dublin, the official insurance agency for the Irish Yachting Association. Their quote was no lower than another company’s, but I had been impressed by the personal interest shown. I was paying £200 for coverage in British and Irish waters, single-handed, and another £150 for the Azores race and the single-handed return.

One piece of equipment required by the rules of the race was an emergency radio transmitter which would operate on two civil aviation frequencies, to be used in case of losing the boat and taking to the life raft. This signal would be picked up by a commercial airliner, then the rescue services would use the beacon to help locate the raft, which would be very difficult indeed if it had to be located visually. Blondie Hasler, one of the founders of the OSTAR, would probably not approve of this equipment, since he was against any competitor making any use of the rescue services. He has been quoted as saying, a competitor who got into trouble “... should have the decency to drown like a gentleman and not bother the rescue people.” I was perfectly happy to have the transmitter aboard.

I was becoming increasingly concerned at the lack of progress on the boat. Barry Burke, who is the second most charming man in Ireland (the most charming man in Ireland, and the nicest, is Dr. Eamonn Lydon, of Oranmore, County Galway), would, whenever I would come to him, perplexed about the boat’s progress, place a fatherly hand on my shoulder and say, “Now, Stuart, your boat is the most important boat being built in this yard, because of what she has to do, and you just can’t rush a boat like that.”

Everything else seemed to be moving along on time, however. One day a few weeks before, the area engineer for Lucas, the electrical equipment people, had turned up at the yard unexpectedly and said he had heard from Hydromarine, the engine people, that I needed a second, larger alternator. He said that Lucas would be happy to provide it and any technical advice I needed, and now the engine had arrived, the big alternator bolted into place.

Now came the passage to Lymington on Irish Mist II, and it proved to be all that the Golden Apple delivery had not. We slipped our moorings at Crosshaven in the early evening on Friday, May 31: Archie O’Leary, the owner; Pat Donovan, a Crosshaven publican and regular winch grinder and cook on Mist ; Peter Walsh, a Cork gynecologist (just in case); and a student who was studying yacht design in Southampton, to whom I shall refer as The Kid.

We were soon close reaching in a steady Force six, gusting seven, as darkness closed. In these conditions, watches were being kept in pairs, and Archie put me with him, obviously anxious about my lack of experience.

I had made a point, from the beginning, of communicating to the people I sailed with that I was new to larger boats, because I did not want anybody to overestimate my skills, but lately, this was beginning to become a problem. By the time we sailed on Mist I had some twelve hundred miles of offshore experience and had taken an extensive course in coastal navigation, plus about ten days of practical instruction, a week of that on Creidne, a larger boat than Irish Mist. This was probably more than your average weekend yachtsman would do in two whole seasons, and I could now do, competently, just about anything that needed doing on a boat, barring mechanical and electrical repairs, for which I showed little talent. Certainly, there were things I didn’t know how to do on specific boats; I had never worked with slab reefing, for instance, which Mist had, but it was simply a matter of becoming familiar with a particular boat’s equipment.

I had also discovered two marked advantages which I possessed, both quite accidental and unlearned, but advantages nevertheless. I didn’t get seasick, apart from an occasional queasiness, and I was not frightened on boats.

Читать дальше