We rowed out to the boats, and an extremely calm and civilized discussion took place. It was agreed that I would give Frank my check for the full amount of the yard’s bill, and he would pay the money into the court for safekeeping. When I returned from the Azores, the matter would be settled. I was happy with the arrangement, as long as it kept the money out of the yard’s hands. As we were preparing to go ashore, I took John Harrington aside and asked him what the hell was going on. Hadn’t we discussed and settled all this? Hadn’t Barry agreed to the arrangements? If he was unhappy, he had had a day and a half to contact me and discuss it. Why hadn’t he done so?

John was acutely embarrassed. He had simply been instructed by Barry that he was putting it into the hands of a solicitor; he was given no details. Now Golden Harp was under arrest, a court order taped to her mast. At least they hadn’t nailed it to the aluminum.

Frank told us to go ahead with our dinner plans, while he and Donegan, the yard’s solicitor, adjourned to Rosie’s, the local pub, to discuss the details of the transaction. We trooped into town to start our belated farewell dinner, and an hour or so later Frank stopped by to say that all was well, we could sail the next morning. We phoned John Rafferty to stop payment on my earlier checks to the yard and to ascertain that funds were available. All was well there, too.

Next morning, after final stowage and the taking of many photographs, we motored down to the yacht club, had lunch and took on ice, then fueled and were off. (On the way out of Drake’s Pool we had scraped our keel across a mudbank, nearly losing Bill over the pulpit, at the exact moment somebody, probably Theo, had fired a parachute flare from the woods in farewell salute.)

As we motored down the river out of Crosshaven, a single Mirror dinghy followed for a time in our wake. The sight brought back a rush of memories. Roche’s Point was soon abeam and, after a lot of sail trimming and adjusting, Harp sailed herself for all of the night, as we began to become accustomed to her.

We spent a fine day sailing, fiddling with Fred (who was reluctant to steer on a beam reach), bailing water (which seemed to be coming from forward somewhere, maybe from the long hull fitting), and continuing to build the boat. Tarka finally divulged that he had spent a year as an apprentice with Hickey Boats in Galway when a lad (he had been fired when the foreman found him making a model airplane during his tea break), and he took on the bulk of what had to be done. Bill navigated and I bailed, using the Jabsco electric bilge pump, which had been fitted for just such an occasion. The shape of the hull precluded any more than about two inches of bilges, so two gallons of water could make the interior a miserable place.

We were at Land’s End in time to see a beautiful moonrise above Cornwall. By midnight Wolf Rock was abeam, and we altered course for the Lizard, the southernmost tip of Cornwall. As we approached it the tide turned against us, and although we were registering several knots on the speedometer clock, we seemed to be standing virtually still. I spent long periods of my midnight-to-three watch sitting on a cushion on the pulpit, my safety harness clipped to the forestay, watching the moon and the water and the night while Fred steered. It was one of the most beautiful nights I have ever spent on a boat.

By midday Monday we were motoring in a flat calm, and I was using the VHF radio constantly. The Dynafurl had revealed a maddening tendency to separate into two equal halves, and although it could be repaired easily, it was causing us worry; water was entering the boat in increasing quantities, and we were now bailing hourly; and every other fault which had been built into the boat was now surfacing, my own mistakes surfacing, too. During the afternoon a puddle of hydraulic oil collected in the bilges. The trouble was found to be a leaky inspection meter which I should have removed. I sent a telegram to Jeremy Rogers’s Boatyard, the English agents for Steam, who made the Dynafurl, asking for a replacement to be ordered from the States immediately by telephone. Then I rang Camper & Nicholsons and asked for a haulout and repair of whatever was leaking when we arrived in Gosport. The radio hummed all afternoon with such messages. Bill had flatly refused to sail for the Azores unless we could get the leaking stopped in Gosport. I was in full agreement with him. We motored on.

We also used the radio for social purposes. We made a lunch date later in the week with Angus and Murlo Primrose and, since Ann was in France and would not return in time for our departure for the Azores, I spoke with a young lady whom I had met at another sailing event earlier in the season and invited her down to the south coast for a night later in the week. This young lady shall be known in this tale as The Bird.

By mid-afternoon on Tuesday the Needles were abeam and we entered the Solent to find it seething with yachting activity. Cowes Week was due to start on Friday, and the narrow body of water was full of boats practicing. Spinnakers, tallboys, bloopers, and every other sort of sail were everywhere, and it was a very pretty sight indeed. We sailed slowly in light winds past Cowes and past Norris Castle, where Bill’s wife, Anita, was staying with friends. Although I had sailed into the Solent before on delivery trips, never had I seen it so dressed with sail. It was very beautiful.

Late in the evening we berthed at Camper & Nicholsons Marina in Gosport. The next day would be Wednesday. The race started on Saturday, and there seemed to be at least two weeks’ work to do on the boat. Moreover, we were asking for Camper’s help at the worst possible time. The first race of Cowes Week was happening on Friday, and the yard was choked with yachts being readied for the world’s premier week of yacht racing. We wolfed down a takeaway Chinese meal and got the last solid sleep we would have for a week.

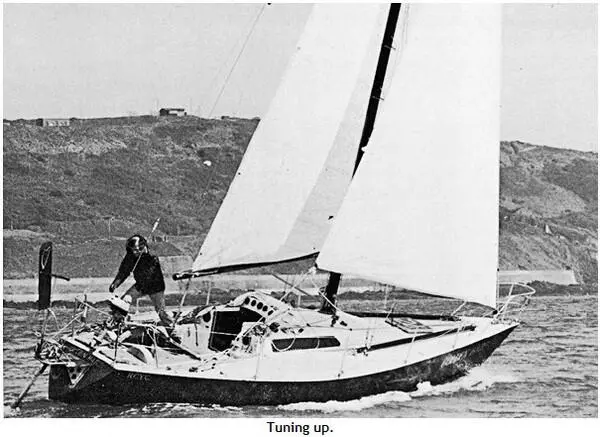

Early Wednesday morning I waylaid Camper’s repairs manager, John Gardner, as he drove through the gate. We went over Harp together, and within the hour she was high and dry, sharing Camper’s crowded apron with the likes of Morning Cloud, Golden Apple, the giant Rothschild yacht, and numberless other French yachts, their bottoms being diligently rubbed down by their crews and their skippers complaining loudly (the French are very good at this) to anyone who would listen. A foreman and crew were assigned to Harp, and by noon her keelbolts had been loosened to let her dry out in preparation for resealing the keel. Tarka had found a leak in the forward bulkhead and the trouble was quickly located. Every time the yacht hit a wave, water was forced through a gap in the glass-fiber seal and into a dead air space under the anchor well, from which it ran through a leak in the “watertight” bulkhead into the forepeak.

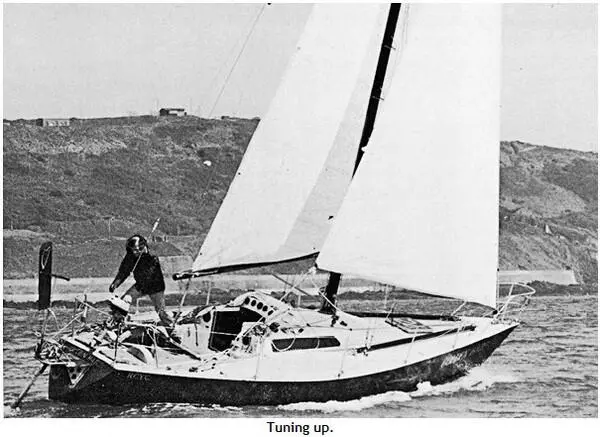

In the afternoon Bill and Tarka left for business in London, to return Friday, and Shirley Clifford rang to say that she would arrive the next day. Robert Hughes from Gibb turned up and spent four hours tuning and refining the self-steering system and refused to accept a penny. Staggering with fatigue, I took him and his wife out for dinner. I slept on Harp, high on the apron, a most peculiar sensation.

I was up at the crack of dawn to let the workmen on the boat and spent most of a frantic day shopping for gear I hadn’t been able to find in Ireland. Shirley turned up in the afternoon, and I gave her a list of things to do. The Bird was not far behind. I had not been able to find a decent place to stay in Gosport, and since I had to go to Lymington anyway to exchange a broken meter at Brookes & Gatehouse and collect the new Dynafurl from Jeremy Rogers, I booked us in at The Angel there. We made a mad dash for Lymington in her car in order to get there before closing time and just made it. Bill Green, Rogers’s man in charge of Dynafurls, broke the news that the replacement hadn’t arrived, then gave me tools and instructions on repairing the existing unit. I left instructions to send the replacement on to the Azores so that it would be there when we arrived.

Читать дальше