“I don’t believe we’ve met,” he said to me.

His cool gray eyes made me feel like I was on a game show and didn’t know the answer.

“Antsy, this is my dad,” Gunnar said.

“Pleased to meet you,” I said, then silence fell again as everyone ate.

I don’t do well with silence, so I usually take it upon myself to end it. My brother says I’m like the oxygen mask that drops when a plane loses air pressure. “People stop talking and Antsy falls from the ceiling to fill the room with hot air until normality returns.”

But what if normality is never going to return, and you know it?

I opened my mouth, and words began to spill out like I was channeling the village idiot. “Working today? Yeah, my dad works on Saturdays, too. We got a restaurant, so he’s always working when people are eating, and people are always eating—of course that’s different from being a lawyer, though—isn’t that what Gunnar said you do? Wow, it must have been hard work becoming a lawyer—a lot of school, just like becoming a doctor, right? Except, of course, you don’t gotta practice on dead bodies.”

I was feeling light-headed, and then realized I had said all that without breathing. I figured maybe I should have put my own oxygen mask on first before helping others, like you’re supposed to.

Gunnar didn’t say anything—he just stared at me like you might stare at a car wreck you pass on the side of the road. It was Kjersten who spoke.

“He wasn’t at work,” she said, almost under her breath.

“More chicken?” Mrs. Ümlaut asked me.

“Yes, please, thank you.” But even as I tried to plug up my mouth up with food, I couldn’t stop myself from talking. “My dad had one of his recipes stolen by a restaurant down the block and he says he should sue—maybe you can be his lawyer, or at least tell him if it makes sense to sue, because I hear it costs more money than it’s worth, and then there are like fourteen thousand appeals and no one ever sees a penny—of course I could be wrong, you’d know better than me, right?”

He seemed neither amused nor irritated. I would have felt much more comfortable if he were one or the other. “I’m not that kind of lawyer,” he said flatly, between bites of food. Gunnar continued his car-wreck gaze, although I think by now it was a multicar pileup.

“Something to drink, Antsy?” Mrs. Ümlaut asked.

“Yes, please, thank you.” She poured me a tall glass of milk, and I quickly began to drink—not because I wanted it, but because I knew that unless I was a ventriloquist and could make words come out of somebody else’s mouth, drinking would shut me up for a good twenty seconds, and maybe the urge to blather would go away like hiccups.

It worked. Once the glass was drained, my words were drowned. The rest of the meal was filled with an unnatural silence, in which no one made eye contact with anyone else, least of all with Mr. Ümlaut. I made it through the meal listening to clinking silverware, and the ticking of the clock, until Gunnar finally rapped me on the arm and said, “The dust bowl awaits.”

I had never been happier to get away from a dinner table, and it occurred to me that this was the first time in the Ümlaut home that it felt as if someone was dying.

It was dark now, with nothing but the back-porch bulb to light up the backyard. We sprayed until both drums of herbicide were empty. Gunnar had brought with him the silence of the dinner table. It drove me nuts, because, just like with his father, I had no idea what he was feeling or thinking—and although I swore to myself I wouldn’t bring it up, I couldn’t leave without asking Gunnar the big question.

“So what’s the deal with your dad?”

Gunnar laughed at that. “The deal,” he said. “That’s funny.” And that’s all he said. He didn’t tell me that it was none of my business, he didn’t tell me to go take a flying leap. He just brushed it off like the question had never been asked.

He took a quick glance at the instructions on his herbicide canister. “Says here that the plants will all be dead in five days, and then it should be easy to pull them out.”

“We could sign over two extra days of life to the plants if you want to wait until next weekend,” I said, and laughed at my own joke.

“That’s not funny.”

“Sorry.”

To be honest, I had no clue what I was and wasn’t allowed to laugh at anymore.

The moment was far too uncomfortable, so I tried to salvage it. “Hey, by the way, I think there are still a few people at school willing to donate months, if you still want them.”

“Why wouldn’t I want them?” he asked. “As Nathaniel Hawthorne said, ‛ Scrounging for precious moments is the most primary human endeavor.’”

He was always so matter-of-fact about it, you could almost forget what was happening to him. Like the end of his life was just an inconvenience.

“Does it ever... scare you?” I dared to ask him.

He took a while before he answered. “A lot of things scare me,” he said. Then he looked at his unfinished gravestone in the middle of the dying yard. “No doubt about it—I’m going to have to start over.”

***

Before I left, I stopped by Kjersten’s room. She was sitting at her desk, doing homework. I suppose she was the type of student who would do homework on a Saturday. I knocked even though the door was open, because there’s this instinct we’re born with that says you don’t walk into a girl’s room uninvited, and even when you’re invited, you don’t walk in too far unless, of course, you’re related to each other, or her parents aren’t home.

“Hi,” I said. “Whatcha doin’?”

“Chemistry,” she said.

“Are you studying whether we got chemistry?”

She laughed. I have to say, this whole you’re-attractive-when-you’re-embarrassed thing was great. It was like a free license to say all the things I’d never actually have the guts to say to a girl, because the more embarrassed it made me to say it, the more it worked in my favor.

She turned her chair slightly toward me as I stepped in. Still riding on the fames of my chemistry line, I thought I might actually dredge up the guts to sit on the edge of her bed . . . Then I realized if I did, I wouldn’t be much for conversation, because the phrase My God, I’m sitting on Kjersten’s bed would keep repeating over and over in my mind like one of Christina’s Himalayan mantras, and I might start to levitate, which would probably freak Kjersten out.

So instead of sitting down, I kind of just stood there, looking around.

“Nice room,” I told her. And it was: it said a lot about her. There was a NeuroToxin concert poster on the wall, next to a piece of art that even I could recognize as Van Gogh. There was a mural on her sliding closet doors that she clearly had painted herself. Angels playing tennis. At least I think they were angels. They could have been seagulls—she wasn’t that great of an artist.

“I like your mural,” I said.

She grinned slightly. “No you don’t, but thanks for saying so.” Like I said, people can pick up my emotions like a pod-cast. “I like painting, but it’s not what I’m good at,” she told me. “That’s okay, though, because if I was good, then I’d always worry if I was good enough. This way I can enjoy doing it, and I never have to care about being judged.”

“In that case,” I said, “I really DO like your mural. I wish I had the guts to do things I stink at.”

She took a measured look at me. “Like what?” she asked.

Now I was put on the spot, because there were so many things to chose from. I thought of her on the debate team, and finally settled on, “I’m not very good speaking in front of an audience.”

Читать дальше

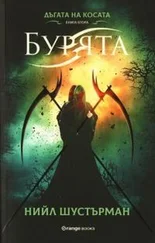

![Нил Шустерман - Жнец [litres]](/books/418707/nil-shusterman-zhnec-litres-thumb.webp)