The Basque language wasn’t written down until the sixteenth century. It has a fiendishly complex grammar and it looks alien, certainly to the European eye, full of z s and x s. Just counting from one to ten is a challenge: bat bi hiru lau bost sei zazpi zortzi bederatzi hamar . Its obscurity proved a rather useful secret weapon during the war in the Pacific in the Second World War. The US army bamboozled the Japanese intelligence services by sending coded messages in Basque (as well as Navajo, Iroquois and Comanche). Basque-speaking marines were used to send and receive the transmissions; the phrase to signal the beginning of the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942 was ‘Egon arretaz x egunari’ (‘Heed the x day’).

The language of Euskara, as the Basque people call it, is spoken today by around 600,000 people in seven traditional regions — four in Spain and three in France. While the Basque language in France has been subjected to the same fate as all the French regional languages and has no official status, the Spanish Basques have enjoyed a much greater degree of political and cultural autonomy. Euskara did suffer after the Spanish Civil War, when the language was outlawed under the dictatorship of General Franco. Chef Juan Arzak remembers being punished for speaking Euskara in school. A Basque nationalist movement grew under Franco; since his death, Spanish Basques have regained some self-rule powers, but the nationalist movement continues — in its most extreme form as the terrorist organization ETA.

Today, Euskara has co-official status with Spanish in the region, and the number of speakers is growing. Children can choose to attend schools where all lessons are in Euskara and Spanish is taught as a second language. There’s a Euskara-language television and radio station, newspapers and books in Euskara. A Royal Academy of the Basque language is charged with watching over Euskara, protecting it and establishing standards of use. It’s a daunting task. The younger generation of Basques tends to speak euskañol , an informal mixture of Euskara and Spanish. But people like Chef Arzak aren’t worried. The Basque food he cooks is a mixture of the traditional and the avant-garde and draws on dishes and ingredients from other food cultures; in the same way, the Basque language is able to incorporate words and expressions from other languages. It’s a pungent metaphor for a unique language.

The Basques are fortunate in having mountains, rivers and the sea to define their borders and repel invaders. This has without doubt helped them to preserve their language when many other minority languages in Europe have withered. The Diaspora of the Jews could easily have resulted in the disappearance of their language, as they were absorbed into other cultures, but their resistance against anti-Semitism and the strength of their religious life meant that Hebrew was kept alive during centuries of exile until, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, the state of Israel was created, and Hebrew was adopted as the national language.

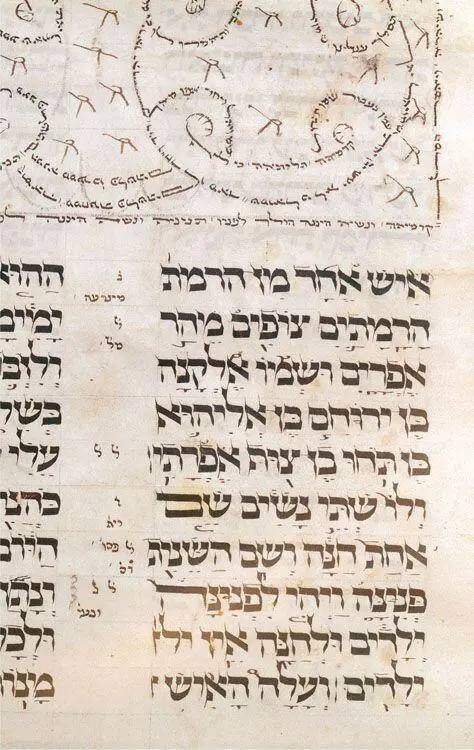

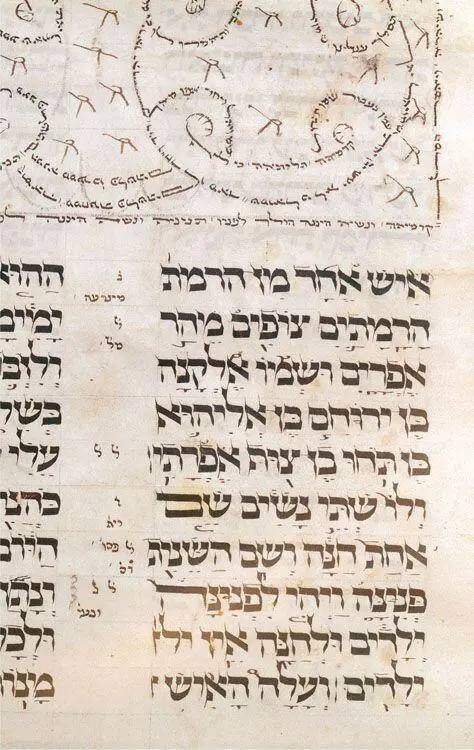

Samuel extracted from a fourteenth-century Hebrew Bible

Whatever one thinks of Israel, its achievment in inculcating a sense of identity is without doubt one of the success stories of the postcolonial era. The country had a tricky birth, a difficult childhood and a tempestuous adolescence. It has been an extraordinary journey to nationhood, and language has been at the core of keeping it together.

Dr Ghil’ad Zuckermann is a leading Israeli linguistician, as people who study linguistics are properly called to differentiate them from linguists. He tells a story of five Jews who influenced the world. It goes like this:

Moses said, ‘The Law is everything.’

Jesus said, ‘Love is everything.’

Marx said, ‘Money is everything.’

Freud said, ‘Sex is everything.’

Einstein said, ‘Everything is relative.’

He sees the punchline as a lesson on language, specifically modern Hebrew, which he calls Israeli. ‘Israeli is a very complex language,’ he says. Its revival has been a ‘relative success’, a mish-mash of old Hebrew and different bits of other languages, a hybrid affair — just like everything else in life.

Not everyone’s laughing, though. Ghil’ad, who was born in Tel Aviv and is the Professor of Linguistics and Endangered Languages at Adelaide University in Australia, is a controversial figure in Israel. His line on Hebrew annoys a great many people: he argues that the Hebrew of the modern state of Israel is not, as most linguists believe, a revival of the ancient language which hadn’t been spoken for nearly 2,000 years. Israelis are not speaking like the prophet Isaiah, he insists. Neither does he accept the theory of relexification — that modern Hebrew is, in essence, Yiddish (the language most of the early settlers spoke) with Hebrew words. Not true either, he says. Ghil’ad argues that Hebrew is a synthesis, a language with more than one parent, a beautiful mongrel, a hybrid. It is genetically both Indo-European and Semitic. Ancient literary Hebrew and Yiddish are the primary contributors, and there is an array of secondary influences, like Arabic, Russian, Polish, German and Ladino (Judaeo-Spanish), all languages spoken by the Hebrew revivalists.

Ghil’ad’s thesis challenges the traditional linguistic wisdom that, with a bit of tinkering and adding of new words, modern Hebrew sprang directly out of the ashes of ancient liturgical and literary Hebrew, which had once been spoken all over the Jewish world. It also annoys politicians and scholars, who accuse him of pushing a political, post-Zionist agenda. The early Zionists emphatically linked the revival of Hebrew to their claim of an ancient birthright in the land of Israel, so the modern state doesn’t appreciate a linguistician who says that Israelis aren’t actually speaking the language of the prophets.

These arguments matter because the story of Hebrew is not just the story of a language. It’s about history and nationhood and identity — and the battle for survival.

For centuries Hebrew was the language in what is now Israel-Palestine, generations before a man called Jesus ever walked the streets of Jerusalem. But after the Diaspora, when the Jews scattered throughout Europe following the revolts against the Romans in the first and second centuries AD, Hebrew died out as a spoken language. It became a linguistic Sleeping Beauty, read, recited and remembered only in the Torah, the rabbinical tradition and Friday-night suppers in Jewish homes. In the nineteenth century, the movement for a Jewish homeland, a return to Zion after 2,000 years of persecution, began to take hold. And with it came the dream of reviving the language of the ancients.

Rishon LeZion is a bustling suburb of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1882, one of the first Zionist settlements, and in 1886 the first Hebrew school was created there. This was the brainchild of the prime mover behind the revival of Hebrew, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a Jewish lexicographer and newspaper editor. He had learned written Hebrew as part of his religious upbringing, and at one time thought of becoming a rabbi, but instead he became increasingly interested in the nationalist movements in Europe and ideas of self-determination. He believed that, if Jews returned to their ancient land and began to speak their own language, they could once again become a nation. For him, Hebrew and Zionism were one: ‘The Hebrew language can live only if we revive the nation and return it to the fatherland,’ he wrote. So, in 1881, he moved with his family to Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire.

Читать дальше