He was the original Man with a Mission, writing newspaper articles about reviving Hebrew and speaking only Hebrew with every Jew he met, despite the lack of current vocabulary. The Hebrew he used was the language of the synagogue, of psalms and prayers and the Torah, and a flowery literary tradition which was heavily mixed with Aramaic. But Eliezer was passionate in his conviction that, with training and practice and the necessary creation of new words, Hebrew could and should be resurrected as a spoken language. He was a bit of a tyrant and insisted his family speak only Hebrew, not Yiddish or their native Russian. His son, Ben-Zion, was not allowed to come into contact with any other language, and Eliezer boasted that, as a result, his son was the first native speaker of Hebrew. Ben-Zion wrote later in his autobiography that he was sent to bed if foreign visitors came to the house, and that when Eliezer came home one day and found his wife absent-mindedly singing a Russian lullaby to Ben-Zion, there was a furious shouting match.

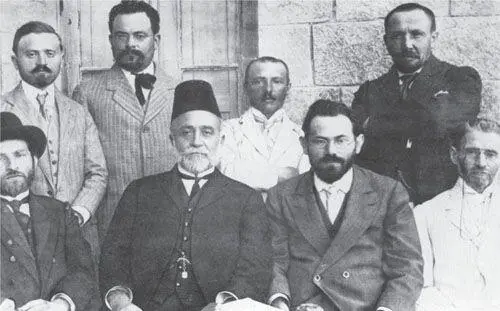

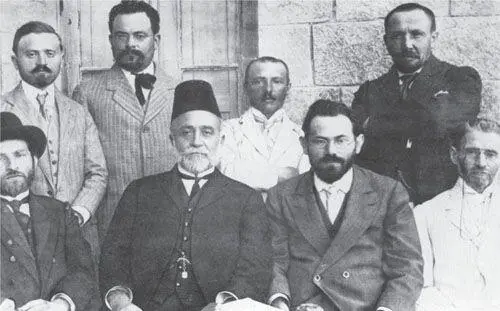

Members of the Hebrew Language Council in 1912

Eventually, it was the successive waves of Jewish immigrants from all over the world which secured the revival of spoken Hebrew. In the last decades of the nineteenth century and early ones of the twentieth, thousands of Jews flooded into Palestine, mainly from Eastern Europe and Russia, and Hebrew schools were set up, where the medium of teaching for everything was Hebrew.

Of course, the teachers weren’t native Hebrew-speakers either. They were mostly Ashkenazi Jews, and their language was Yiddish. They tried to teach the best Hebrew that was available to them, but it was very difficult. ‘In a heavy atmosphere, without books, expressions, words, verbs and hundreds of nouns, we had to begin teaching,’ wrote one teacher from the 1920s. ‘We were half-mute, stuttering, we spoke with our hands and eyes.’ When it came to making new words, ‘everyone, of course, used his own creations’.

It’s a key point in Ghil’ad Zuckermann’s argument for the hybridization of Hebrew. The early settlers and teachers — what he calls ‘the founder population’ — spoke Yiddish or Polish or Russian and, he says, they could not rid themselves of their native grammatical structures. And a Yiddish-speaker pronounced Hebrew differently from, say, a Sephardic Jew from Yemen. Ghil’ad argues that this early influence of Yiddish-speakers on Hebrew left an indelible trace on its structure and word order. ‘Yiddish speaks itself beneath Israeli,’ he says. ‘Had the language revivalists been Arabic-speaking Jews [from Morocco, for example], Israeli Hebrew would have been a totally different language — both genetically and typologically, much more Semitic.’

By the end of the First World War, Hebrew was consolidating its position as the national language-to-be. There was a movement in favour of Yiddish, the lingua franca of the middle European Jew, but it could not throw off the taint of the shtetl , the pogroms and the poverty. The Zionists wanted to re-establish the link to the older story, the ancient Jewish history and the centuries of nationhood, and Yiddish was despised as second-class and polluted.

In 1909, the first Hebrew city, Tel Aviv, was established. The entire administration of the city was carried out in Hebrew, and people were forced to speak Hebrew. Street signs and public announcements were written in Hebrew. Hebrew was so dominant in Tel Aviv that, in 1913, one writer announced that ‘Yiddish is more treif [non- kosher] than pork. To speak it a person needs great courage.’ Yiddish-speakers were shouted at in the street — ‘Jew, speak Hebrew’ — or even beaten up by gangs of men from the creepy-sounding Defenders of the Language Brigade.

In 1921, Hebrew became one of three official languages in British-ruled Palestine (along with English and Arabic), and then in 1948, with the founding of the state of Israel, it was made an official language along with Arabic. Today it is the most widely spoken language in Israel.

But what if Israel had chosen Arabic as its main national language? Would it have been a means of reconciliation between Jew and Arab? Ghil’ad Zuckermann wonders, if Israelis and Palestinians had literally been able to understand each other, whether it could have changed the political story and prevented the cumulative violence and antagonism of the years after 1948. The two languages are so close, Hebrew and Arabic (although Ghil’ad says Arabic has far better curses and swear words), but not close enough to overcome what are essentially ancient tribal differences and conflicts which go all the way back to the story of the separation of Isaac and Ishmael. To this day the word in Hebrew for Arab is Ishmael.

The reason for Hebrew’s success is the other side of the same coin: it had a fervent, strong ideology of a national movement. People wanted a common language to unify them, all these Jews coming from all over the world and speaking different languages. Hebrew succeeded through political will, and a strong identity which both secular and religious Jews have used for their own purposes.

Yiddish: Not Just for Schmucks

Yiddish has been called, variously, the language of the ghetto and the shtetl , a barrier to assimilation, a mutilated and unintelligible language without rules, the mother tongue, the true language of the Jewish people — and a dozen other things, some complimentary, some not. At its height before the Second World War, it was understood and spoken by an estimated 11 million Jews, but it lost the battle with Hebrew to become the national language of Israel, and the number of Yiddish-speakers has dwindled rapidly since. And yet it survives, albeit spoken principally in the United States and by the ultra-orthodox in Israel. As the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer said, ‘Yiddish has not yet said its last word.’

In fact, Yiddish has borrowed and assimilated so many words from other languages, and given so many in return, especially to English (think schmalz, chutzpah, schmutz, bagel, shmooze), it’s easy to forget it’s not a sort of Jewish-American form of English. It’s a proper language, a hybrid of medieval German and Hebrew, using the Hebrew alphabet, with dashes of Aramaic and Slavic languages thrown in. It developed among the Ashkenazi Jews living along the Rhineland around the tenth century, and then spread through central and eastern Europe. The ancient tongue of the Jews in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, Hebrew, had been in decline as a spoken language since the Jews were defeated by the Babylonians in the sixth century BC, and well before the time of Jesus it had been replaced by Aramaic as the Jewish vernacular. But Hebrew remained the written language of religion, of the liturgy, the Torah and the scholars.

Yiddish — which means ‘Jewish’ — takes about three-quarters of its vocabulary from medieval German, but it has borrowed liberally from Hebrew and from many other lands and cultures where the middle European Jews lived. It has tremendous richness of expression, and the vigour and subtlety of a mongrel creation, like English, which amasses words from all over the place.

It developed a rich vocabulary to express the human condition, often using humour to rail against suffering and the absurdities of life, which was a useful antidote to the pogroms, persecution and expulsions. Many of the terms have found their way into English, because there is no equivalent English word which can convey the depth and precision of the Yiddish. There’s a tremendous humanity and irony in the sheer range of words to describe the human character in all its failings and strengths. For example, what other language would distinguish between a schlemiel (someone who suffers through his own actions), a schlimazl (a person who suffers through no fault of his own) and a nebach (a person who suffers because he makes other people’s problems his own)? There’s an old joke which explains the distinction: the schlemiel spills his soup, it falls on the schlimazl , and the nebach cleans it up.

Читать дальше