Yiddish has been a potent force in Jewish identity and the struggle for survival. But as Jews became assimilated into the local culture, particularly in Germany from the late 1700s and into the 1900s, Yiddish began to decline. It was criticized by Jews, particularly those most influenced by the ideals of the Enlightenment, as a barbarous ghetto jargon, a barrier to Jewish acceptance in German society.

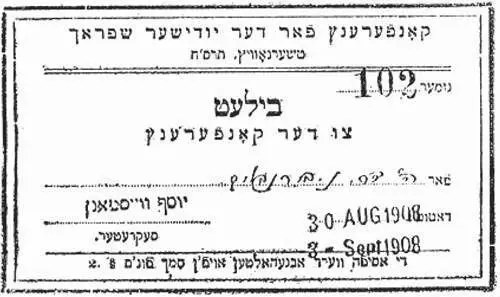

In 1908, the first Yiddish Language Conference was held in Czernowitz, Bukovina (now Chernivtsi, Ukraine). It was supposed to be about standardizing the language and promoting and celebrating its thriving literature and drama, but it became a fierce argument about the status of Yiddish relative to Hebrew, and which could truly lay claim to being the national Jewish language. Politics, history, tradition and the future all got mixed up with debates about language, and there was a great deal of passionate speech-making, including a keynote address from the writer I. L. Peretz. ‘There is one people — Jews,’ he declared, ‘and its language is — Yiddish. And in this language we want to amass our cultural treasures, create our culture, rouse our spirits and souls and unite culturally with all countries and all times.’

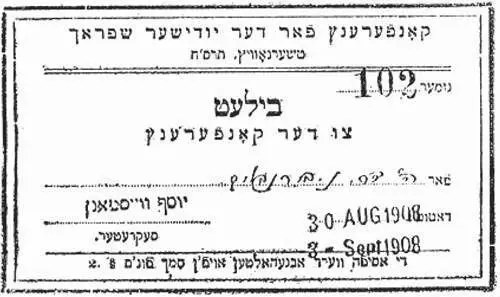

Ticket to the first Yiddish Language Conference, 1908

It’s interesting that the creator of Esperanto, Ludovic Zamenhof, was also part of the debate about Yiddish and Hebrew, but he took a different and independent view. He had created Esperanto to be a uniting force for good in a disparate world. He believed that a new, international language could bring people of different cultures and nations together; everyone would have their own languages, but Esperanto would be the vehicle for equality and understanding and peace among everyone. Later in life, he took his vision even further; he dismissed Yiddish and Hebrew, and a physical Jewish state in Palestine, and argued that Esperanto was the language to promote a broader spirituality, and bring together Jews the world over in a new kind of mystical humanism.

As the Zionist movement gathered momentum, more and more Jews from around the world, speaking many different languages, began to return to Palestine, and, in the end, Yiddish lost out to a revived and modernized Hebrew. After the Second World War it was even more tainted with the memories of the Holocaust, and the modern state of Israel turned its back on it. The once thriving language of middle Europe survives mainly amongst the elderly Jewish communities in New York, Florida and California and, of course, in the world of comedy and entertainment.

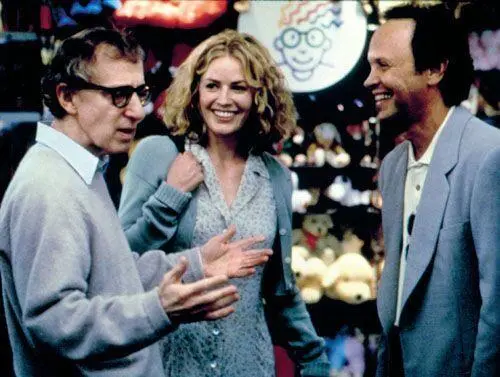

The Friar’s Club in midtown Manhattan looks like a medieval castle inside, but it’s a castle owned and controlled by the court jesters. Founded as a private members’ club in 1904, it has been a bastion for entertainers, and especially comics, for over a century. Will Rogers, Jack Benny, Jerry Seinfeld, Billy Crystal — well pretty much every major and minor American entertainer — have graced the oak-panelled rooms. And, of course, this being New York, it is the Jewish comedians who have dominated the scene. Stewie Stone is a veteran of the so-called ‘Borscht Belt’. Also known as the Jewish Alps, the Borscht Belt was like a mini Las Vegas that flourished between the 1930s and the 1960s in the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York. It was a place where the predominantly Jewish population of NYC would go for their summer vacations and listen to the quickfire repartee of stand-up comedians, many of whom would become household names — Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, George Burns, Jackie Mason, Phil Silvers and Joan Rivers, to name just a few, and, of course, the irrepressible Stewie Stone, whose Yiddish humour is rooted in the fertile comic soil of Flatbush in Brooklyn, where he grew up.

Jewish comedians Woody Allen and Billy Crystal with Elizabeth Shue in Deconstructing Harry, 1998

Stewie, with his broad Brooklyn accent, is a powerful advocate for Yiddish. Holding court around a pool table at the Friar’s Club, he expounds: ‘It’s a great language for saying the man’s a dick. As the snow is to Eskimos, so schmuck is to the Jew. The definition of a schmuck is a guy who gets out of the shower to take a piss. A schlemiel is a loser, and a nebach is like a waste of time. You can talk to a schlemiel — I’ll sit and have a drink with him — but a nebach — you don’t want nothing to do with a nebach .’

Ari Teman, a young Brooklyn comic, concurs: ‘The nebach is the guy getting the water when you’re going on a football team,’ and, quick as a flash, Stewie responds: ‘For an older Jewish audience, if you said “ass” on stage, you were dirty. “Kiss my ass”, you are dirty. But if you said “kish mein tuchas” there, that was clean, it was accepted. You could curse in Yiddish and not offend anybody.’

Ari adds: ‘I sent a rabbi a joke, and he wrote back the acronym “LMTO”. Normally it’s “laughing my ass off”, but he replaced it with a “tuchas”. “Laughing my tuchas off”, it’s a Yiddish acronym. We’re instant messaging Yiddish acronyms now.’

Stewie continues: ‘When one Jew meets another Jew he’s a landsman [literally countryman], meaning we’re of the tribe. No matter where you are. So two old Jewish men were talking, and one said, “Morris, bei you [according to you], what is a good Shabbat ?” And the other said, “A good Shabbat, bei me, is I get up, I go to school, I doven [pray], I come back, I sit with my grandchildren, and we eat, and I go back to school, and we doven. Bei me, that’s a good Shabbat . Seymour, bei you, what’s a good Shabbat ?” The other man says, “I get up in the morning, I get on a plane, I fly to Vegas, I get off the plane, I go to the crap table, I shoot crap, I win 10,000 dollars, I go up to the room, there’s a chick waiting for me. Bei me, that’s a good Shabbat .” And the other guy says, “Good Shabbat? Bei me, that’s a great Shabbat !” ’

And of course it’s so important that that joke is in Yiddish, that you say Shabbat and you don’t just say Sabbath.

There’s a joke about the shtetl in Poland or southern Russia somewhere, a little village, where the Jews live in perpetual fear of a pogrom. There’s a story in the newspaper of a young teenage girl being murdered, and they’re terrified it’s going to be a Christian girl and that the local community will blame the Jews. Suddenly one of their number runs in and says, ‘I’ve got fantastic news, the murdered girl was a Jew.’ As a joke it’s both terrible and funny, because the Jews were persecuted beyond language. It’s almost unspeakable what happened. And yet always there’s this realist strain of humour.

Stewie develops this serious point: ‘Yiddish is basically our soul, and the kids are starting to go back to it. It’s our heart, our soul. Jews are emotional people. We love to cry, and in Yiddish you can cry. You can’t cry in Hebrew too easily. Judaism is not a religion, it’s a way of living your life. And Yiddish is a way of feeling your life because every time you use these words … it’s taking us back to where we came from, that we all share together. We’re all the same Jew. We’re not a rich Jew or a poor Jew.’

Stewie doesn’t believe that Hebrew can fulfil this function.

Читать дальше