And then it was the turn of the Normans: 1066 and all that. This was the invasion which triggered enormous changes in English, as it developed into what’s called Middle English (the language of Chaucer), leaving behind the inflectional system of Old English with its changing word-endings for the more or less simplified grammar we have today. Not only did English vocabulary increase hugely with the influx of French borrowings, but French became the language of the court and the ruling and business classes. For a while there was a linguistic class division, with the poor and the ordinary people speaking English and the upper classes speaking French.

There was a third language too, though: Latin. Latin was the language of the Church and of learning. Ever since St Augustine and his monks came to Britain in the sixth century, Latin (and Greek) words had been influencing English. During this trilingual period in the later medieval era, words stepped over from one language to another and left their footprints. Huge numbers of French and Latin words entered English, and English was very happy to accommodate them. The habit of borrowing and assimilating became second nature.

That’s why we’re swimming in all these synonyms mentioned at the start — because of the successive layers of borrowed words laid down on our language over the centuries. The majority of synonyms are from two sources — Anglo-Saxon (Old English) origin and the French or Latin origin — and they follow a distinct pattern. In general, Anglo-Saxon words are simple, essential, strong, everyday words in common usage, such as see, good and heart . French- and Latin-derived words are often more sophisticated, or learned or conceptual. Compare see and perceive : they mean the same, but the Latin-derived word would much more likely be used in an official, formal document.

The borrowed words are coloured by how they came into English and the status of the people who brought and used them. Latin was the language of religion and the law and learning, and French, as the language of the court, left a strong literary and cultural footprint. Our basic, concrete and close-to-the-heart words we held on to from Anglo-Saxon. Only about one-fifth of our common English words today are Anglo-Saxon, compared with three-fifths for Latin, Greek and French, but the Anglo-Saxon words are far more frequent. The hundred most frequently used English words are almost all Anglo-Saxon: hand, foot, land, sun, cow, drink, say, have, tree, heart, life, go. And the odd, double-word arrangement we have in English when it comes to types of meat — we call the meat by a different word from the animal it comes from — dates from the Norman period, when they brought their own words bœuf and porc for the products of the animals which had Germanic names — cows and pigs .

The synonyms, the layers, the different influences and endless loanwords all made English the flexible, subtle, vibrant language it is. They made Chaucer and Shakespeare and Joyce possible.

There have always been the purists who objected to the heavy influence of Latin, Greek and other languages on English. William Barnes was a nineteenth-century poet and philologist who argued that English needed to get back to its Anglo-Saxon roots so that ordinary people without a classical education could understand it better. So he came up with rather wonderful alternatives, like sun-print for photograph, welkinfire for meteor and the truly delicious nipperlings for forceps . He was surely outdone, though, by the American science fiction writer Paul Anderson, who set out to write a text which did not use any loanwords from other languages, particularly Latin, Greek or French. This wasn’t just a simple story; his subject was atomic theory, so he had to make up a lot of new words and compounds from Anglo-Saxon roots and words, like waterstuff for hydrogen, bulkbits for molecules or the beautiful uncleftish worldken for atomic physics. He published Uncleftish Beholding in 1989, and it’s as charming and inventive as William Barnes’ efforts a century before.

You Say

Oïl

, I Say

Oc

Homogenization has been with us for a long time: all empires in one way or another try to do it, and language plays a key role. Think of the Romans, the Ottomans, the British, the French — they’ve all imposed their language and customs on their vassal states. It’s much easier to control and govern if everyone speaks the same language. That’s the theory. Of course, in practice it’s a different matter.

The French exported their language all over their colonies — even now we call them Francophone countries — but before they began that process they, like the British in Ireland, had to impose their language within their own borders. However, in France it was a more complicated process because there was not one version of French but two.

Occitan was once spoken by half the population of France, as well as the people of the Occitan valleys of Italy and Monaco and the Aran valley of Catalonia in Spain. It was the language of the medieval troubadours who travelled round the courts of France and Spain, singing poems of chivalry and love.

The name Occitan comes from langue d’oc , literally the language of oc — so-called because, up until the beginning of the seventeenth century, France was divided into two linguistic halves. The northern half, from around Lyon upwards, said oïl for ‘yes’, whereas the southern half said oc . So within France there were the langue d’oïl and the langue d’oc ; the langue d’oc was quite different, a close cousin to Catalan, with stronger roots in Latin.

The first recorded reference to the langue d’oc is in an essay written at the beginning of the fourteenth century by the Italian poet Dante. In De vulgari eloquentia he explored the historical evolution of language. He wrote (in Latin): ‘nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil’ (‘Some say oc, others say si, others say oïl’ ) (‘Some say oc , others say si , others say oïl ’). The oc language was Occitan, the si language was Italian, and the oïl language was French.

Even as Dante was writing, the status of the oc language was under threat as the French royals in the north began to spread their influence into Occitan territory. In 1539, the Edict of Villers-Cotterêts decreed that the langue d’oïl had to be used in all legal documents and laws. The aim was to stop the use of Latin; the effect was to limit the use of regional languages like Occitan.

Outside government, the monarchy didn’t seem to be that bothered about the local languages spoken by their subjects. The French Revolution changed all that. The revolutionaries argued that kings and reactionaries preferred regional languages, as they kept the peasant masses uninformed; the Republic, ‘unie et indivisible’ (‘one and indivisible’), couldn’t be achieved if the spread of new ideas was hindered by patois — a derogatory term used for the countrified, backward languages of non-Parisian French-speakers.

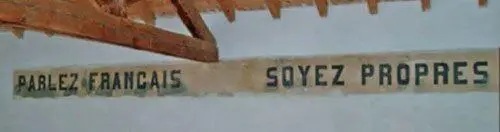

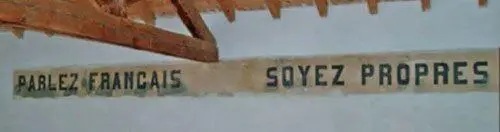

‘Speak French Be Clean’ daubed on the wall of a school

On 27 January 1794, Bertrand Barère, a member of the National Convention who had presided over the trial of Louis XVI, argued in favour of one national language:

The monarchy had reasons to resemble the Tower of Babel; in democracy, leaving the citizens to ignore the national language, unable to control the power, is betraying the motherland … For a free people, the tongue must be one and the same for everyone … How much money have we not spent already for the translation of the laws of the first two national assemblies in the various dialects of France! As if it were our duty to maintain those barbaric jargons and those coarse lingos that can only serve fanatics and counter-revolutionaries now!

Читать дальше