The Gaelic League restored the language to its place in the reverence of the people. It revived Gaelic culture. While being non-political, it was by its very nature intensely national. Within its folds were nurtured the men and women who were to win for Ireland the power to achieve national freedom. Irish history will recognise in the birth of the Gaelic League in 1893 the most important event of the nineteenth century. I may go further and say, not only the nineteenth century, but in the whole history of our nation.

(Michael Collins, The Path To Freedom)

The League proved immensely popular in English-speaking areas of Ireland and by 1908 it had around 600 branches. The non-political stance of Hyde became increasingly unpopular and in 1915 he resigned the League’s presidency after its members committed it to ‘a free, Gaelic-speaking Ireland’ at the annual conference. Many of those members participated in the Easter Rising the following year and helped set up the Irish Free State a few years later.

Hand in hand with the revitalization of the Irish language at the end of the nineteenth century was a literary revival which saw the flourishing of some of Ireland’s greatest writers. Sitting at the centre of this extraordinary blossoming, in her black widow’s weeds, was the figure of Lady Gregory, who, along with her friend William Butler Yeats, was the driving force of the revival.

Described by George Bernard Shaw as ‘the greatest living Irishwoman’, she was born Augusta Persse in 1852, the youngest daughter of a Unionist landowning family in Galway. At the age of twenty-seven, the plain-faced Augusta climbed to the top of the social ladder when she married widower Sir William Gregory, a retired Governor of Ceylon, who owned neighbouring Coole Park estate. He was thirty-five years older than his new wife. The couple spent much of the 1880s travelling or in London, where their house was filled with literary luminaries of the day — Browning, Tennyson, Henry James.

When her husband died in 1892, Augusta donned the widow’s weeds which she wore until her own death forty years later and retreated to Galway, to the family house at Coole Park. Widowhood seemed to inspire her. She learned Irish and began collecting local stories and translating them into the Anglo-Irish dialect of her local area, Kiltartan.

The playwright Edward Martyn — later to become the first president of Sinn Féin — was a neighbour, and it was during one of her visits to his home at Tullira Castle that she met W. B. Yeats. This was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two. The redoubtable widow tried to teach the young writer Irish but with little success. Yeats is reputed to have tried and failed on thirteen separate occasions to learn to speak the language.

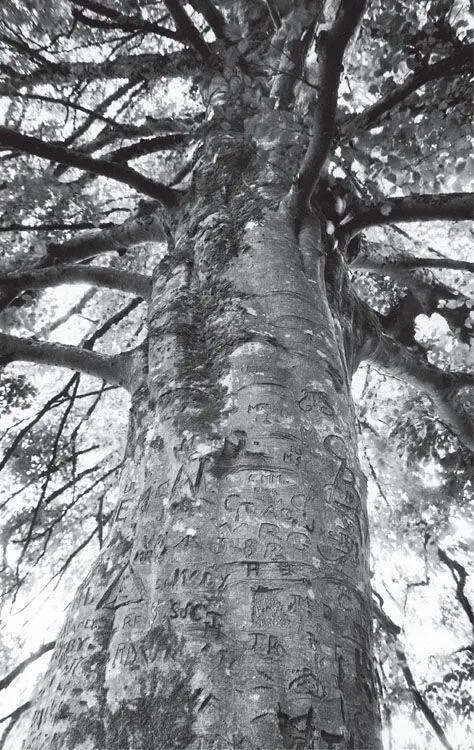

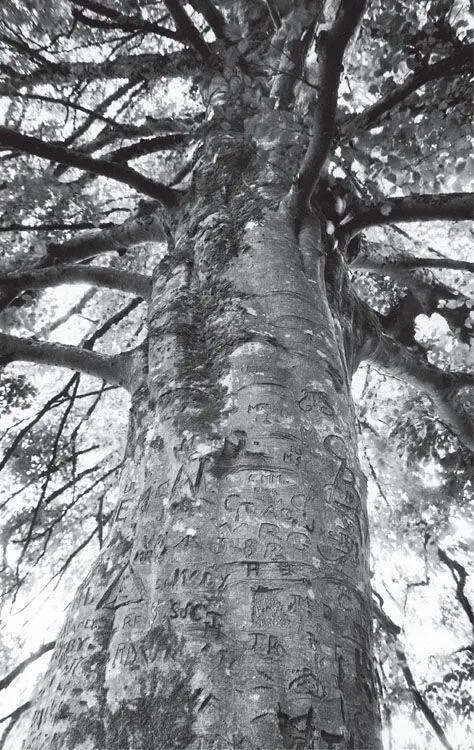

Lady Gregory’s home at Coole Park became a summer retreat for Yeats and other writers of this Irish Revival. There’s a giant copper beech still standing in the grounds of Coole Park known as the Autograph Tree. Carved into its trunk are the initials of its summer visitors, amongst them Yeats, J. M. Synge, Sean O’Casey, George Russell (AE) and George Bernard Shaw. Out of these long summer sojourns came the idea for the Irish Literary Theatre, which Lady Gregory, Yeats and Martyn set up in 1899. Its aims, according to its manifesto, were: ‘to build up a Celtic and Irish school of dramatic literature … to bring upon the stage the deeper thoughts and emotions of Ireland’.

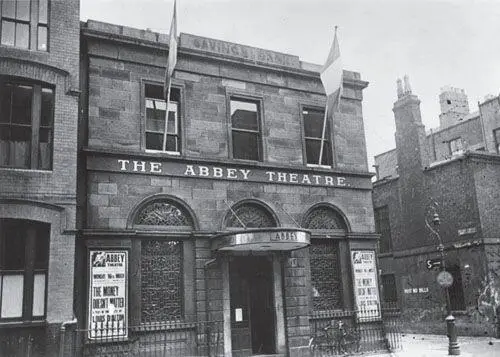

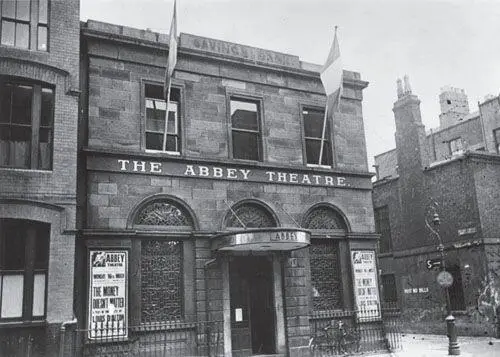

The project collapsed due to lack of funds, but the Irish National Theatre Society was set up soon after, and out of this came Dublin’s famous Abbey Theatre — seen by many as the cornerstone of the Irish Revival. The Abbey was immediately popular with audiences, but first and foremost it was a writers’ theatre, a hugely influential nursery for playwrights and actors.

George Bernard Shaw described Lady Gregory as ‘the charwoman’ of the Abbey; she turned her hand to anything and everything. She wrote over forty plays, directed, acted and raised funds. When crowds rioted at the opening of Synge’s controversial The Playboy of the Western World in 1907, one observer described Lady Gregory as ‘as calm and collected as Queen Victoria about to open a charity bazaar’.

Lady Gregory died in her beloved Coole Parke home in 1932, in a newly independent Ireland. Her influence on the revival of an Irish literature was huge; her effect on the revitalizing of the Irish language less so. The numbers of Irish-speakers in the census of 1926 had fallen to just over 500,000, the lowest level ever.

Lady Gregory was one of the few members of the Abbey Theatre who spoke Irish well; most of the work to come out of the literary revival was written in English, or rather in Hiberno-English, the version of English spoken in Ireland. But this was an English never seen before, one word put after another in the service of a good sentence with more skill and artistry than had almost ever been seen before. The influence of the Irish language on the writing of Yeats and Joyce and Beckett was fundamental. Here’s Declan Kiberd, Professor of Hiberno-Anglo Literature at University College Dublin, on the subject.

Lady Isabella Augusta Gregory, a founder of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin

The Autograph Tree, Coole Park

The Abbey Theatre in Dublin, founded to further the cause of the Irish Cultural Revival

‘You have to remember that Irish as a language was spoken up till the 1840s and 50s by many, perhaps the majority of Irish people. So it’s a backdrop to all this. People made the transition from Irish to English so rapidly that many were thinking in Irish while using English words and they taught themselves English out of books. So they acquired strange pronunciations of their own, they re-routed the genius of the English language down new circuits, and I believe this is one of the reasons for the explosion of writing at the beginning of the twentieth century in Ireland. You can explain this in a very concrete way. You know in Standard English, if you want to emphasize a word you do it tonally: “Are you going to town tomorrow?” or “Are you going to town tomorrow ?” But in Irish you bring the key word forward in the sentence, “Is it you that’s going to town tomorrow?” “Is it tomorrow that you’re going to town?” And that can sound quite poetic to an ear that’s trained in Standard English because it’s a deviation. If you map this on to a wider attitude, to the rules of literature, people like Joyce and Yeats and Beckett, they broke so many of the rules with abandon because they didn’t have any superstitious investment in English literary traditions, they were in the end at an angle to them. So the freedom with language becomes a freedom with form in general.

‘Hiberno-English has other grammatical idioms which are very similar to Irish. For example, Irish has no pluperfect tense and uses the phrase tar eis , which means “after”. Hiberno-English imitates this and, instead of saying “I have just done”, it says “I was after doing”. ”Why did you hit him?” “He was after punching me.”

‘Irish doesn’t have words for yes and no and instead repeats the verb in question. Hiberno-English uses yes and no much less frequently than Standard English. “Is it cold outside?” “It is.” “Are you coming in?” “I am.” ’

Читать дальше