Perhaps it was because Ireland’s writers didn’t have Milton or Dryden or Tennyson breathing down their necks that they were able to draw on the Irish language, or at least the memory of that language — even though they couldn’t speak it themselves.

Politics, so often the force which kills off a language, became the Irish language’s best friend. The Irish Free State established in 1922 — later to become the Republic of Ireland — made the restoration of the Irish language part of government policy. The new constitution declared Irish to be the national language; it was made compulsory at school and speaking it was a prerequisite for any job in the civil service. Gaeltacht areas — the native Irish-speaking areas — were officially recognized. These Gaeltachts are mostly in the remote areas of the west of the country, in Donegal, Mayo, Galway, Kerry and Cork.

But the measures came too late — and the government’s efforts were seen by many to be too heavy-handed. The teaching of the Irish language in schools tended to be dull, the learning difficult. Irish lessons came to be dreaded by schoolchildren in the same way as many are in terror of Latin — a dead language, grammatically difficult, removed from everyday life and to be dropped the minute one leaves school.

Today, most people in Ireland, including those in Gaeltacht areas, no longer speak Irish as a first language. The most recent figures suggest that only a quarter of households in the Gaeltacht areas are fluent Irish-speakers. Irish may be the first official language of the Republic but it’s certainly not spoken by the majority of its people.

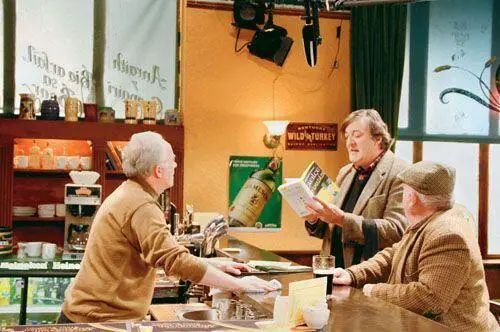

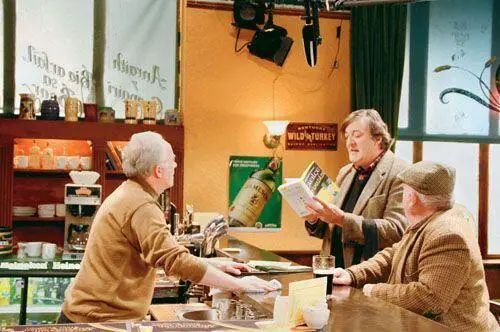

Attempts to keep Irish alive continue. Raidió na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht Radio) and Teilifís na Gaeilge (Irish-language Television, or TG4) have had limited success, but the jewel in the crown is an award-winning TV soap in Irish called Ros na Rún. The entire crew from first AD to best boys, gaffers and cameramen all speak to each other in fluent Irish. They provide a useful sounding board for where people think the Irish language is now. The producer, Hugh Farley, predicts that Irish is always going to be a second language for the majority of Irish people. He does, however, note a new ‘coolness’ about Irish.

Stephen appearing in Irish-language soap Ros na Rún

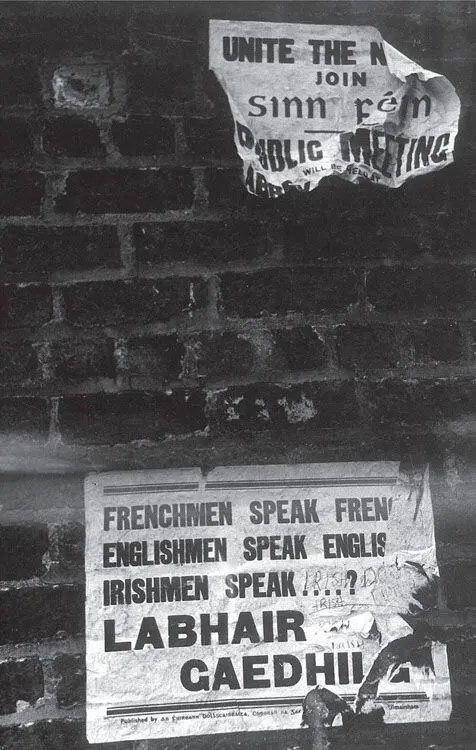

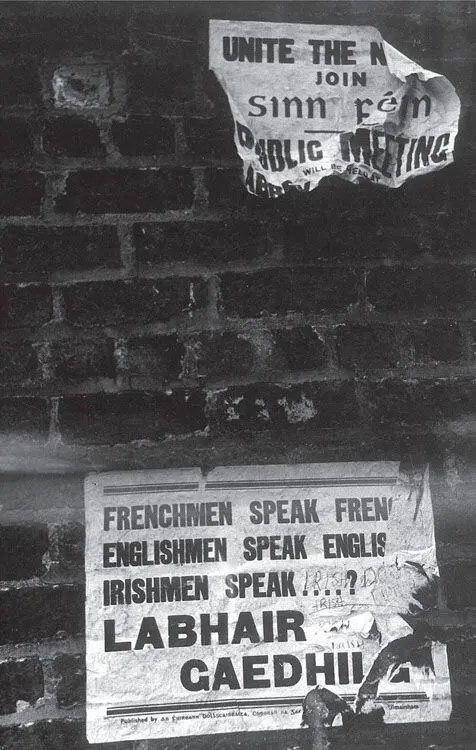

Posters on a wall in Dublin promoting Irish

‘I know that if you were to speak to some of the cast here who grew up in the area they’d say that within a generation or so they can remember going into Galway City and being laughed at because they were speaking the Irish language. It was held in such low status. I think that has changed in recent years, particularly in Dublin because of the growth of Gael schools. So actually the great and the good, the bourgeoisie, wanted to send their kids to Irish-language school because they believed they were going to get a better education through the Irish language.’

The future of the language may indeed rely on the urban communities of Irish-speakers who are sending their children to Irish-language gaelscoileanna in droves. Nearly 10 per cent of all schoolchildren attend these schools, the fastest-growing sector of education in the country. All of the standard curriculum lessons are taught in Irish — apart from English, of course.

The pupils at one of these schools have interesting ideas about when it is that they use English and when Irish. English, for instance, is the language of the internet and definitely of texting. The grammar of written Irish is fiendishly complicated, so book-reading for pleasure is usually in English as well. No Gaelic Harry Potters here. But Irish is the language of the playground and out shopping with friends and chatting on the phone. It’s the language of everyday life. Will they keep on speaking Irish, or is the language in terminal decline? Hugh Farley is unsure.

‘I think that we have as a nation a very ambivalent attitude to the language … The Irish feel kind of culturally embarrassed that they are not good at the language and they are slightly resentful that they can’t speak it fluently and therefore they try to discard it … I think that the trouble is we’re caught in the double bind. We have people within the Gaeltacht areas [where] the younger generation are speaking it less than ever before and the number of people who are learning Irish and using it outside of the Gaeltacht is increasing. So we may be in a situation in twenty years’ time where there are more people who are non-native speakers of the language who are keeping the language alive rather than people who live indigenously and speak it natively.’

Nipperlings and Waterstuff — the English Story

Think about these pairs of words for a minute: lawful and legal; goodwill and benevolence; help and aid . The first thing, obviously, is that they have similar meanings — they’re synonyms, after all, and the English language is very, very rich in synonyms. But the second thing is: although they’re words of similar meaning, don’t you think they feel different? Isn’t there something deep in the character, the personality almost, of the words that triggers differing responses in you? If you went to someone in desperation, you wouldn’t say, ‘I need aid, please!’ Goodwill has a more personal, practical feel than benevolence. Lawful suggests something more ethical and substantial than legal .

It’s not just about usage: these are subtle but unmistakable shades of meaning which are the result of different linguistic roots. The first words are Anglo-Saxon or Old English in derivation, and their synonyms are Latinate or French-based. These words and thousands like them came to us from different times in our history and along different paths. Over the centuries the English language has been coloured and seasoned by those linguistic journeys. And more than that: the words tell us about our history, and where we come from.

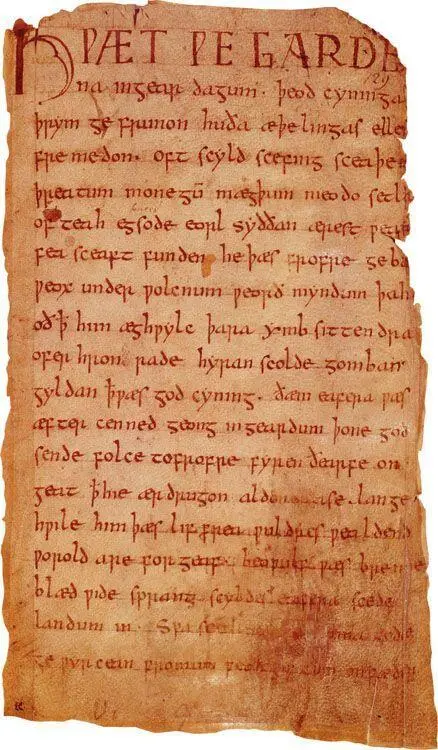

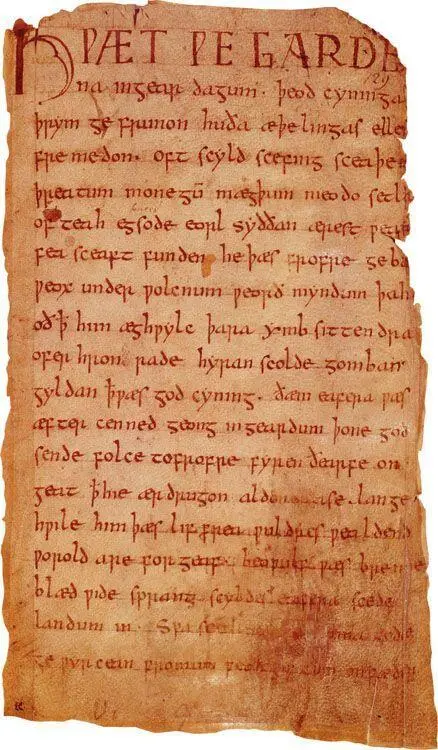

We’ll get back to the synonyms, but a bit of history first. English as we know it today was shaped principally by three periods of settlement and invasion: new peoples arrived on our shores and brought their languages with them. In the fifth and sixth centuries, it was those strangely named tribes which every schoolchild used to reel off parrot-fashion — the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes. They sailed over from the north-western coastline of continental Europe, from present-day Denmark and northern Germany. They pushed most of the Celtic-speaking Britons north and west, mainly into what’s now Wales, Scotland and Ireland, and their Germanic language developed into what we now call Old English. It looks and sounds just like a foreign language to a modern English-speaker (the epic poem Beowulf is written in Old English), but the fact is that about half of the words we most commonly use today have Old English roots, like be, strong, water. They are the bedrock of our language.

Extract from Beowulf c .1000

A few centuries later, there was another wave of invasion, and another layer added to the language mix. The Vikings were on the move. From the middle of the ninth century large numbers of Norse invaders came racing over the North Sea, raiding, trading and settling in Britain, particularly in the north and east. They came in such numbers, and were so successful, that by the eleventh century the whole of England had a Danish king, Canute. Their language was also a Germanic variety, Old Norse, and it had a deep influence on Old English. This is when very basic words like take and they come into the language, along with huge numbers of other loanwords, from the Scottish kirk to all these placenames with — by on the end, meaning ‘village’ or ‘settlement’.

Читать дальше