Peach-faced Lovebirds also sometimes form stable homosexual pairs; as in Galahs, these are probably lifelong bonds that usually originate while the birds are still youngsters. Same-sex pairs of Lovebirds also engage in frequent mutual preening. In their courtship and sexual activity, some homosexual pairs combine elements of male and female behavior. In female pairs, for example, each partner may feed the other (a typically male activity in heterosexual pairs) or invite the other to mount (a typically female activity). Other pairs are more role-differentiated, with one bird performing the behaviors most typically associated with males while the other exhibits the patterns of a female. However, in their parenting behaviors both members of female homosexual pairs adopt typically “female” duties. After having investigated several potential nest sites, they jointly select a suitable cavity that they occupy together, and each female contributes to building the nest. In Peach-faced Lovebirds, this involves a unique method of collecting nesting material: long strips of bark, grass, or leaves are tucked directly into the birds’ back and rump feathers to be carried back to the nest. Both partners lay eggs (usually infertile) and simultaneously incubate them. In contrast, male homosexual pairs never build nests.

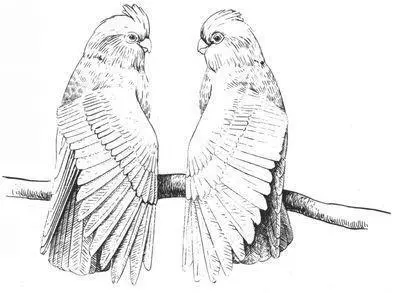

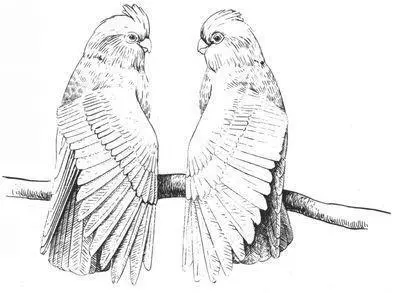

A homosexual pair of female Galahs performing a mirror-image “wing-stretching” display

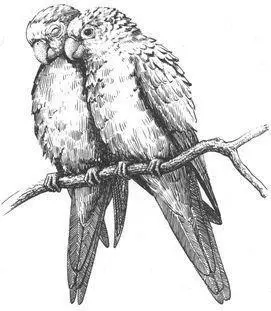

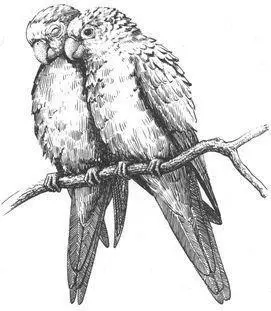

A male Orange-fronted Parakeet nuzzling his male pair-mate

Both male and female homosexual pairs also occur in Orange-fronted Parakeets. Same-sex couples often sit side by side—sometimes for half an hour or more at a time—preening and nuzzling each other while fluffing their plumage. Males also sometimes engage in sexual behavior with their pair-mate: one bird mounts the other, usually preceded by a display known as FAWNING or CLAWING, in which he lifts one foot in the air and places it gently on the other male’s back or wing. Female partners often COURTSHIP-FEED each other: one bird regurgitates some food and feeds it to her mate, and the two partners interlock their bills while jerking their heads back and forth. Unlike in heterosexual pairs, either bird may feed the other. This is usually accompanied by several stylized visual and vocal displays such as head-bobbing, rubbing or kneading of the bill on the branch (often producing a distinctive popping sound), fluffing of the cheek feathers, and flashing the iris of the eyes while whistling. The two mates sometimes play-fight with one another by BILL-SPARRING, in which they grasp and tug at each other’s beak. Female pairs may also jointly prepare a nest, usually constructed in arboreal termite nests: one partner excavates the entrance tunnel (as do males in heterosexual pairs) while the other hollows out the nest chamber (as do females in heterosexual pairs). Some female couples successfully compete against heterosexual pairs for nesting sites; pair-bonded females often become powerful allies that support one another and may even come to dominate opposite-sex pairs through attacks and threat behavior.

Frequency: Homosexual bonds are common in these Parrot species. In some captive populations of Galahs, for instance, one-half to two-thirds of pair-bonds are between birds of the same sex. A study of Peach-faced Lovebirds in captivity revealed that 4 of 12 pair-bonds (33 percent) were between females; a similar study of Orange-fronted Parakeets found 5 of 9 pair-bonds (56 percent) between females. Although male homosexual pairs of Orange-fronted Parakeets have been documented in wild birds, the overall incidence of same-sex bonds in the wild is not known for any of these species. However, about 1 out of every 180 nests of wild Galahs contains a SUPERNORMAL CLUTCH of 10–11 eggs, double the number of most other nests. These are undoubtedly laid by two females, perhaps members of a homosexual pair (although they could also result from alternative heterosexual arrangements—see below).

Orientation: Among captive Galahs that form some sort of pair-bond, about 44 percent of birds only form homosexual bonds, another 44 percent only develop heterosexual pairings, while about 11 percent bond with birds of both sexes. Of the latter group, a variety of bisexualities occur, usually in the context of trios or quartets of birds. One female, for example, formed a polygamous bond with two males, then went on to develop a bond with another female while maintaining her trio bond. Another female was bonded to a male who also had another female partner; she then “divorced” him and paired with another female. One male in a homosexual pair later also developed simultaneous bonds with two females. Similar bisexual trios and quartets also occur in Orange-fronted Parakeets, and females in this species sometimes compete successfully against both males and other females for the attentions of another female. In wild Galahs (especially males), it is possible that many birds form same-sex pairings in the juvenile flocks, with some later developing opposite-sex associations as adults. In Lovebirds (as well as in Galahs and Parakeets that only form same-sex pairs), at least some birds in homosexual bonds appear to be more exclusively same-sex oriented. For instance, bonds sometimes form between females even if there are available unpaired males, and one widowed female Lovebird who lost her female partner went on to form another homosexual pairing.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Although most heterosexual bonds in Galahs are lifelong and between only two birds, several other variations occur: some birds form polygamous trios (as discussed above), while 6–10 percent of Galahs divorce their partners and seek new mates. Infidelity in the form of copulations by paired Galahs with birds other than their mate is common, especially during the incubation period. Sometimes a mated pair changes partners after their eggs have been laid, usually resulting in loss of the eggs (accounting for about 2 percent of all clutches that fail to hatch). In addition, parenting in this species is not confined to a strictly nuclear-family structure: youngsters from several different families are pooled together into a CRÈCHE or “day-care” flock as soon as they are old enough to leave the nest. This allows their parents to forage on their own (although a few tending parents are always on hand in the crèche). Youngsters spend nearly as much time in these crèches as they do being cared for solely by their parents in the nest. Sometimes two pairs share the same nest hollow, with both females laying eggs in a combined clutch.

Although divorce and alternative bonding arrangements are not as prominent among Lovebirds, there is nevertheless often considerable antagonism between the sexes in heterosexual pairs. Males tend to become sexually ready each season before females; as a result, their courtship advances are frequently ignored or rejected, and females may even respond with overt aggression. Heterosexual copulations often do not culminate in ejaculation because the female refuses to allow the male to remain mounted, walking or flying out from under him while making threatening displays at him. A similar asynchrony in male and female sexual cycles may also occur in Galahs: in some years, males become ready to mate before females, but by the time the latter are ready, the males often lose interest and many pairs end up not breeding at all. Besides pairs that do not reproduce in a particular year, there is always a sizable proportion of single birds. As many as 60 percent of the adult Galahs in foraging flocks are nonbreeding birds from the nomadic population. Sometimes a nonbreeding female associates regularly with a breeding pair, “tagging along” with the male when he leaves the nest (perhaps in the hope of pairing with him). Such birds are known as “aunts” even though they are probably not related to the birds they associate with.

Читать дальше