Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As discussed above, there is a large segment of nonbreeders in the Pied Kingfisher population: as many as 45-60 percent of males do not mate heterosexually. Remarkably, studies have shown that the reproductive systems of primary helpers are actually physiologically suppressed, since they have reduced male hormone levels, small testes, and no sperm production. Only one in three primary helpers goes on to mate after being a helper, and it is likely that some never breed for their entire lives. In contrast, secondary helpers do not have dormant reproductive systems, but are in most cases simply unable to find female mates due to the greater proportion of males in most populations. Because secondary helpers are not genetically related to the birds they assist, a large number of Pied Kingfishers are involved in “foster-parenting.”

Sexual activity between male and female Blue-bellied Rollers is notable for its nonreproductive components: it occurs at all times of the year (not just during the breeding season), and it often involves nonprocreative REVERSE mounts or mounting without genital contact. In addition, multiple copulations—far in excess of what is required for fertilization—are common. Not only do birds mount each other repeatedly in a single session (dozens of times, as mentioned above), but both males and females may copulate with many partners, sometimes several times each with up to three birds in a row.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Douthwaite, R. J. (1978) “Breeding Biology of the Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis in Lake Victoria.” Journal of the East African Natural History Society 166:1–12.

Dumbacher, J. (1991) Review of Moynihan (1990). Auk 108:457–58.

Fry, C. H., and K. Fry (1992) Kingfishers , Bee-eaters, and Rollers . London: Christopher Helm.

*Moynihan, M. (1990) Social, Sexual, and Pseudosexual Behavior of the Blue-bellied Roller , Coracias cyanogaster: The Consequences of Crowding or Concentration . Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 491. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Reyer, H.-U. (1986) “Breeder-Helper-Interactions in the Pied Kingfisher Reflect the Costs and Benefits of Cooperative Breeding.” Behavior 82:277–303.

———(1984) “Investment and Relatedness: A Cost/Benefit Analysis of Breeding and Helping in the Pied Kingfisher ( Ceryle rudis ).” Animal Behavior 32:1163–78.

———(1980) “Flexible Helper Structure as an Ecological Adaptation in the Pied Kingfisher ( Ceryle rudis rudis L.).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 6:219–27.

Reyer, H.-U., J. P. Dittami, and M. R. Hall (1986) “Avian Helpers at the Nest: Are They Psychologically Castrated?” Ethology 71:216–28.

Thiollay, J.-M. (1985) “Stratégies adaptatives comparées des Rolliers ( Coracias sp.) sédentaires et migra-teurs dans une Savane Guinéenne [Comparative Adaptive Strategies of Sedentary and Migratory Rollers in a Guinean Savanna].” Revue d’Écologie 40:355–78.

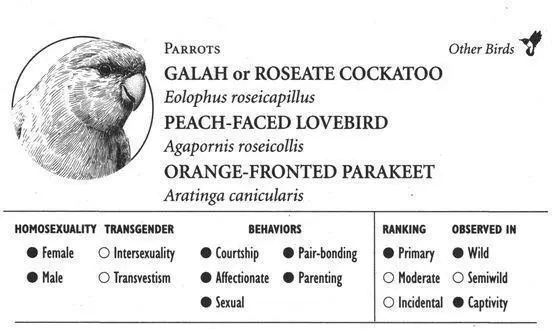

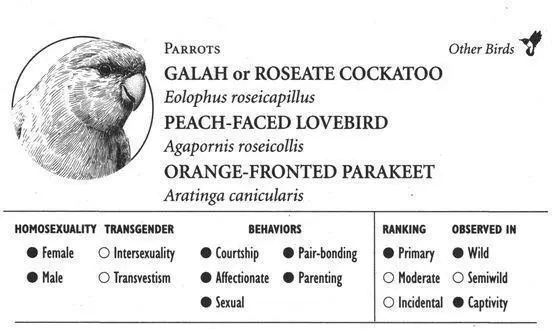

GALAH

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized parrot (about 14 inches) with a pale pink forehead and crest, rose-pink face and underparts, and gray upperparts. DISTRIBUTION: Interior Australia. HABITAT: Savanna woodland, grassland, scrub. STUDY AREAS: Healesville Sanctuary and Monash University, Victoria, Australia; Helena Valley, Western Australia.

PEACH-FACED LOVEBIRD

IDENTIFICATION: A small parrot (6 inches) with a short tail, green plumage, blue rump, and a red or pink breast and face. DISTRIBUTION: Southwestern Africa. HABITAT: Savanna. STUDY AREAS: Cornell University, New York; University of Bielefeld, Germany.

ORANGE-FRONTED PARAKEET

IDENTIFICATION: A small parrot with green plumage, a long tail, and an orange forehead. DISTRIBUTION: Western Central America from Mexico through Costa Rica. HABITAT: Tropical and scrub forests. STUDY AREAS: Near Managua, Nicaragua; University of Kansas and University of California—Los Angeles; subspecies A.c. canicularis and A.c. eburnirostrum .

Social Organization

Galahs and Peach-faced Lovebirds are gregarious birds, gathering in large flocks that can number up to several hundred in Lovebirds and up to a thousand in Galahs. They typically form mated pairs, and Peach-faced Lovebirds usually nest in colonies. In addition, there are nomadic flocks of juveniles and younger nonbreeding adult Galahs. Orange-fronted Parakeets are also highly social, traveling in groups of 12-15 birds (often composed of mated pairs) and sometimes forming flocks of 50-200. During the breeding season, pairs generally separate from the flock to nest, although they periodically recongregate in small groups.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Galahs of both sexes form stable, long-lasting homosexual pairs that participate in courtship, sexual, and pair-bonding activities. Same-sex bonds are strong, often developing in juvenile birds and then continuing for the rest of their lives (as do most heterosexual bonds). Homosexual pairs of at least six years’ duration have been documented in captivity. If one partner dies before the other, the remaining Galah may stay single or may eventually form a homosexual (or heterosexual) partnership with another bird. Pair-bonded Galahs almost always stay close to each other (rarely more than a few inches apart), feeding and roosting together both day and night. When one bird flies to a new location, it calls after its mate to join it, using a special two-syllable warbled call that sounds like sip-sip or lik-lik. If another bird intrudes between them, both partners threaten the intruder and may force it to leave by edging it out or simultaneously stabbing their beaks at it. Pair-mates spend considerable time preening each other; this intimate behavior, sometimes known as ALLOPREENING, involves one bird lowering its head in front of the other, allowing its mate to gently nibble and run its bill through the feathers. After a short time the birds switch positions, and often this develops into a playful fencing bout, in which the birds gently clash beaks and dodge each other.

Homosexual (and heterosexual) Galah pairs also perform a number of synchronized, highly stylized displays while perching side by side or facing toward or away from each other. One of the most elegant of these is WING-STRETCHING, in which each bird simultaneously fans open one of its wings. Often, one bird fans its left wing while the other opens its right to give a strikingly symmetrical, “mirror-image” effect, while in other cases each pair member fans the same wing in a parallel, but nonsymmetrical, pattern. Other synchronized displays include HEAD-BOBBING (in which the birds dip their heads down and to the side) as well as crest-raising and feather ruffling. In addition, such activities as self-preening, feeding, and leaf- and bark-stripping can also be performed in unison by pair members—in fact, homosexual pairs synchronize their behaviors about 65 percent of the time. Galahs in same-sex pairs may also court and copulate with each other. Courtship includes a sideways shuffling movement toward the partner with crest raised and facial feathers fanned forward, followed by head-bobbing and BREAST POINTING (in which mates touch their own or their partner’s breast feathers with their beaks). Sexual activity involves one bird mounting the other and making pelvic thrusts against its mate; this may occur even when the birds are still juveniles.

Читать дальше