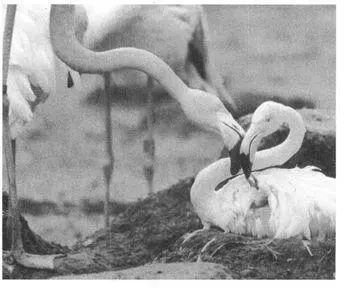

Homosexual couples often engage in parenting behavior. Male pairs incubate, hatch, and successfully raise foster chicks (for example, from a nest they have taken over, or from eggs supplied in captivity). Described as “model” parents, male partners may even “nurse” their chick. Flamingo parents (of either sex) typically feed their chicks a blood-red “milk” produced in their crops, and both males in homosexual couples feed their chicks with this crop milk. Some male pairs, however, do not attempt to acquire eggs, even if they have their own nest, while others do not appear to be interested in parenting at all, since they may roll the egg out of a nest they have acquired. Female pairs take turns incubating eggs on their nest; such eggs may be infertile, having been laid by the females themselves rather than acquired from another nest. As in heterosexual pairs, variation exists in the amount of incubation time contributed by each partner. Some share incubation duties equally, while in other pairs, one female puts in more incubation shifts than the other. Overall, though, females in lesbian pairs contribute about five to six incubation shifts each, which is comparable to the average for heterosexual partners.

Two pair-bonded male Flamingos feeding crop milk to their foster chick

Frequency. In most captive populations with same-sex couples, about 5–6 percent of pairs are homosexual, although some populations have more than a quarter same-sex couples. Although homosexual pairs have not yet been observed in the wild, oversize nests similar to those built by male pairs are found in most colonies and may in fact belong to homosexual pairs (especially considering that most field studies have not systematically and unambiguously determined the sexes of all paired birds).

Orientation: Overall, only a fraction of the population is involved in same-sex pairing. Among these, some individuals have no prior heterosexual experience. However, other Flamingos in homosexual pairs were previously members of a heterosexual pair (and vice versa). Some males in same-sex pairs also occasionally attempt to mount other birds, including females. These are both examples of different types of bisexuality (sequential and simultaneous). In populations with more males than females (or vice versa), many birds remain single rather than forming same-sex pair-bonds, perhaps indicating more of a heterosexual orientation on their part.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Although the standard social unit in Flamingos is the breeding monogamous pair, a number of alternative heterosexual pairing and family arrangements occur. Trios or triads—one male with two females or one female with two males—are fairly common (at least in zoos). Typically all three birds share incubation and chick-raising duties (although no same-sex bonding occurs); in trios with two females, there may be two separate nests, or both females may share a nest. Flamingo pairs also sometimes engage in nonreproductive copulations, mating far in advance of the female’s fertile (or the male’s sperm-producing) period. Many mated pairs are nonmonogamous, with both males and females seeking copulations with outside partners. In one zoo population, 47 percent of the females and 79 percent of the males participated in such “infidelity,” and about 8 percent of all copulations were with outside partners; at another zoo, 25—60 percent of all pairs were nonmonogamous. Furthermore, divorce is extremely common in wild Flamingos: nearly all birds change partners between breeding seasons, and about 30 percent of males even switch mates during the season (in contrast, most pairings in zoos are long-lived).

Once chicks are hatched, a number of social systems are available to relieve the biological mother and father of some of their parenting duties. For example, nonbreeding birds sometimes produce crop milk and “nurse” other birds’ chicks or else act as foster feeders for orphaned chicks. In addition, as they get older, Flamingo chicks typically gather into large nursery groups or CRÈCHES, which may contain several thousand youngsters. These groups provide them with safety in the absence of direct parental supervision, and adults also sometimes feed youngsters other than their own in these crèches. Chicks are often forced into crèches as a result of attacks from adult birds, including their own parents, and crèches may therefore also provide refuge from aggression by other Flamingos. Breeding in wild Flamingos can be irregular, with entire colonies sometimes forgoing reproduction for three or four years at a time—one colony in France failed to produce chicks for 13 out of 34 years (38 percent of the time). In addition, even if breeding is undertaken, it may be abruptly halted, with all or a large portion of the colony—often as many as half of all pairs—abandoning their eggs. Usually it is the female who initiates desertion of a nest.

Other Species

Homosexual pairs occur among both male and female Lesser Flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor) in captivity, including nest-building and (in females) egg-laying. Both sexes participate in homosexual mounting, though only males generally achieve full genital contact. Males in same-sex pairs also sometimes chase and mount females in lesbian pairs, while the latter may mate with males to fertilize their eggs. Most females in homosexual pairs, however, show no interest in males. Pairs of female Scarlet Ibises (Eudocimus ruber) have also been observed in captive flocks, nesting together and sometimes laying fertile eggs.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Allen, R. P. (1956) The Flamingos: Their Life History and Survival. National Audubon Society Research Report no. 5. New York: National Audubon Society.

*Alraun, R., and N. Hewston (1997) “Breeding the Lesser Flamingo Phoeniconaias minor,” Avicultural Magazine 103:175—81.

Bildstein, K. L., C. B. Golden, and B. J. McCraith (1993) “Feeding Behavior, Aggression, and the Conservation Biology of Flamingos: Integrating Studies of Captive and Free-Ranging Birds.” American Zoologist 33:117—25.

Cézilly, F. (1993) “Nest Desertion in the Greater Flamingo, Phoenicopterus ruber roseus.” Animal Behavior 45:1038—40.

Cézilly, F., and A. R. Johnson (1995) “Re-Mating Between and Within Breeding Seasons in the Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus ruber roseus.” Ibis 137:543-46.

*Elbin, S. B., and A. M. Lyles (1994) “Managing Colonial Waterbirds: the Scarlet Ibis Eudocimus ruber as a Model Species.” International Zoo Yearbook 33:85-94.

Kahl, M. P. (1974) “Ritualized Displays.” In J. Kear and N. Duplaix-Hall, eds., Flamingos, pp. 142-49. Berkhamsted, UK: T. and A. D. Poyser.

*King, C. E. (1996) Personal communication.

*———(1994) “Management and Research Implications of Selected Behaviors in a Mixed Colony of Flamingos at Rotterdam Zoo.” International Zoo Yearbook 33:103-13.

*———(1993a) “Ondergeschoven Kinderen [Supposititious Children].” Dieren 10(4):116—19.

*———(1993b) “Ongelukkige Flamingo Liefdes [Tales of Flamingo-Love Gone Awry].” Dieren 10(2):36—39.

Ogilvie, M., and C. Ogilvie (1989) Flamingos. Wolfeboro, N.H.: Alan Sutton.

*Shannon, P. (1985) “Flamingo Management at Audubon Park Zoo and the Benefits of Long-Term Research.” In AAZPA Regional Conference Proceedings, pp. 226—36. Wheeling, W.Va.: AAZPA.

Читать дальше