Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, the most common social unit among these species of Rails is not the heterosexual pair or nuclear family, but the communal group. In some populations of Pukeko, each such group may include up to seven nonbreeding individuals who assist in parental duties. These “helpers” (offspring from previous years) may delay their own reproductive careers for up to three years (one or two years in Tasmanian Native Hens, where an average of 18 percent of adults are nonbreeders). Some physiological mechanisms may be involved in this breeding suppression, since Pukeko helpers often have underdeveloped reproductive organs. In addition to several forms of polygamy, a number of other mating and parenting arrangements are found in these groups. For example, although all birds in Tasmanian Native Hen groups usually mate with each other, sometimes only one male-female pair actually has reproductive copulations. This social system has been called GENETIC MONOGAMY (because only one couple breeds) within SOCIAL POLYGAMY (since multiple partners mate with each other). In addition, although most group members remain together for life, females occasionally “divorce” their mates and join a new group; in some cases, this may lead to a female parenting young that are not her own. Occasionally, she may behave aggressively toward these foster chicks, even expelling them from the group. More violent confrontations sometimes occur when chicks stray into neighboring territories, where they may be killed by the resident group members. However, chicks are sometimes also adopted by neighboring groups, in both Tasmanian Native Hens and Dusky Moorhens.

Among breeding Pukeko, up to five males may court and mount the same female in quick succession—in these cases, one or more of the males may not actually inseminate the female. In fact, the “success” rate for most heterosexual copulations is not high: between one-half and two-thirds do not involve full genital contact and so do not result in insemination. Females often resist heterosexual advances by refusing to allow males to mount them, pecking at males who do mount them, preventing genital contact by not raising their tails, and prematurely terminating mating attempts. Copulations also occur when females are not fertile—for example, long before egg laying begins—and some males mate repeatedly without ever fathering any offspring that year. Similarly, mounts without genital contact account for more than a third of Dusky Moorhen matings and 60 percent of Tasmanian Native Hen matings. A few of these are REVERSE copulations, in which the female mounts the male. Incestuous matings are also common in Pukeko and Tasmanian Native Hens. Nearly two-thirds of all Pukeko heterosexual copulations in some populations are between related individuals, including mother-son, father-daughter, and brother-sister matings. More than 40 percent of Tasmanian Native Hen breeding groups contain related adults that mate with each other (mostly siblings); in addition, about 10 percent of copulations involve parents mounting their own offspring, including young chicks.

Other Species

Stable homosexual pairs often form among Cranes (e.g., Grus spp.) in captivity, a group of birds that is closely related to Rails.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Archibald, G. W. (1974) “Methods for Breeding and Rearing Cranes in Captivity.” International Zoo Yearbook 14:147-55.

Craig, J. L. (1990) “Pukeko: Different Approaches and Some Different Answers.” In P. B. Stacey and W. D. Koenig, eds., Cooperative Breeding in Birds: Long-term Studies of Ecology and Behavior, pp. 385-412. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

*———(1980) “Pair and Group Breeding Behavior of a Communal Gallinule, the Pukeko, Porphyrio p . melanotus.” Animal Behavior 28:593-603.

———(1977) “The Behavior of the Pukeko.” New Zealand Journal of Zoology 4:413—33.

Craig, J. L., and I. G. Jamieson (1988) “Incestuous Mating in a Communal Bird: A Family Affair.” American Naturalist 131:58-70.

*Derrickson, S. R., and J. W. Carpenter (1987) “Behavioral Management of Captive Cranes—Factors Influencing Propagation and Reintroduction.” In G. W. Archibald and R. F. Pasquier, eds., Proceedings of the 1983 International Crane Workshop, pp. 493—511. Baraboo, Wis.: International Crane Foundation.

Garnett, S. T. (1980) “The Social Organization of the Dusky Moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa Gould (Aves: Rallidae).” Australian Wildlife Research 7:103-12.

*———(1978) “The Behavior Patterns of the Dusky Moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa Gould (Aves: Rallidae).” Australian Wildlife Research 5:363-84.

Gibbs, H. L., A. W. Goldizen, C. Bullough, and A. R. Goldizen (1994) “Parentage Analysis of Multi-Male Social Groups of Tasmanian Native Hens ( Tribonyx mortierii ) : Genetic Evidence for Monogamy and Polyandry.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 35:363—71.

Goldizen, A. W., A. R. Goldizen, and T. Devlin (1993) “Unstable Social Structure Associated with a Population Crash in the Tasmanian Native Hen, Tribonyx mortierii.” Animal Behavior 46:1013-16.

Goldizen, A. W., A. R. Goldizen, D. A. Putland, D. M. Lambert, C. D. Millar, and J. C. Buchan (1998) “‘Wife-sharing’ in the Tasmanian Native Hen ( Gallinula mortierii ): Is It Caused By a Male-biased Sex Ratio?” Auk 115:528—32.

*Jamieson, I. G., and J. L. Craig (1987a) “Male-Male and Female-Female Courtship and Copulation Behavior in a Communally Breeding Bird.” Animal Behavior 35:1251-53.

———(1987b) “Dominance and Mating in a Communal Polygynandrous Bird: Cooperation or Indifference Towards Mating Competitors?” Ethology 75:317-27.

Jamieson, I. G., J. S. Quinn, P. A. Rose, and B. N. White (1994) “Shared Paternity Among Non-Relatives Is a Result of an Egalitarian Mating System in a Communally Breeding Bird, the Pukeko.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B 257:271-77.

*Lambert, D. M., C. D. Millar, K. Jack, S. Anderson, and J. L. Craig (1994) “Single- and Multilocus DNA Fingerprinting of Communally Breeding Pukeko: Do Copulations or Dominance Ensure Reproductive Success?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91:9641—45.

*Ridpath, M. G. (1993) “Tasmanian Native-hen, Tribonyx mortierii.” In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 2, pp. 615—24. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

*———(1972) “The Tasmanian Native Hen, Tribonyx mortierii. I. Patterns of Behavior. II. The Individual, the Group, and the Population.” CSIRO Wildlife Research 17:1—90.

*Swengel, S. R., G. W. Archibald, D. H. Ellis, and D. G. Smith (1996) “Behavior Management.” In D. H. Ellis, G. F. Gee, and C. M. Mirande, eds., Cranes: Their Biology, Husbandry, and Conservation, pp. 105—22. Washington, D.C.: National Biological Service; Baraboo, Wis.: International Crane Foundation.

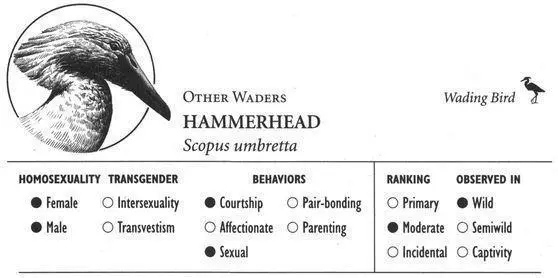

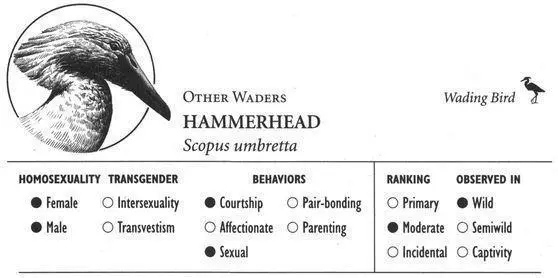

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized brown, storklike bird with a prominent crest almost as long as its bill. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout tropical Africa from Senegal to east and south Africa; Madagascar. HABITAT: Wetlands, including savanna and woodland near water. STUDY AREAS: Near Niono, Mali; Karen and Nairobi, Kenya.

Читать дальше