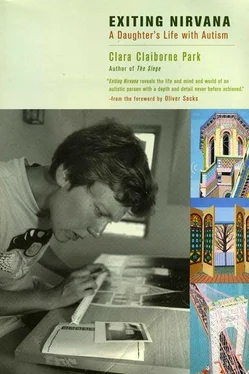

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Chapter 11

«Guess what! Some of the people at work are my friends!»

Jessy is still learning from consequences. Now, however, penalties and rewards arise naturally out of the situation — just as they do for Darth Vader and the rest of us. If she’s rude in the restaurant, she won’t get to go next week. But Jessy is no longer limited to direct experience. Growth and the years continually open up new avenues of social learning. There are movies; there’s TV. Above all there is print. The hard work of her teachers has borne fruit. Jessy can read.

And she does read. Slowly willingness and skill increase together, and with them knowledge and to some extent under-standing of the world she lives in.

When school ended for Jessy some twenty years ago, her reading — after nine years of intensive effort — was just adequate for simple, factual, predictable material. An unwelcome task at school, at home it was limited to things with a clear payoff, like cookie recipes. Without support, reading threatened to join the other skills that had withered from lack of practice. Jessy had learned pottery, knitting, needlepoint, even weaving, from one young helper or another. All, though she had seemed to enjoy them, were abandoned when the companion left. She certainly didn’t enjoy reading. Yet she needed to read daily, and not only recipes. She needed to read stories about people and the things they do. Yet the last story we’d read at home was a four-year-old’s picture book, with no more than a few sentences of text.

But I remembered how she’d enjoyed reading the contracts. Those too were a kind of story, a story about Jessy and the things she did. That pointed the way. We would read as we had then, together, comfortable, warm and easy.

We read aloud, to rivet attention through both eye and ear. She resisted at first; I recognized the old inertia. But I didn’t want to tackle it with a reward this time; that wasn’t what reading was about. So I went back to earlier methods, luring her to read as I had lured the toddler who couldn’t tolerate something missing into putting rings on a stick. Then I had put on all the rings but one; now I read, stopped, and Jessy supplied — she had to — the next word. First the next word. Then the next sentence. Then we took turns, so Jessy had to follow each sentence and couldn’t tune out. And then she began to follow the story within the sentences. Touchingly, she asked for stories about «girls who misbehave».

We read book after book. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series might have been designed to fill in the gaps for a person without a childhood. Not only does Laura misbehave, she grows, and the books with her. She’s four in the first book, and her short, simple sentences were easy even for Jessy. Soon Jessy claimed as her own any paragraph that had Laura in it. She was less interested in personalities, of course, than the concrete things she could understand; to this day she can tell you about the long winter («from November to the end of April») when the train couldn’t get through and the Ingallses almost starved. But we pressed on through adolescence and got Laura married before we found Beverly Cleary’s Ramona series. That was better yet; Ramona was five at the start and really misbehaved; she had tantrums and lay on her bed and kicked the wall. And as Ramona grew and went to school and struggled to control her temper so people would like her, Jessy’s language and social comprehension expanded together. Year after year we went through series after series about girls and families, in the Midwest, in Norway, in Brooklyn, before we got to Dorothy and Oz. Then we stopped. Jessy didn’t want me beside her anymore. She was probably tired of my running commentary — it was too much like a lesson. But she kept on reading.

Jessy has been reading Oz books ever since; so far she’s read thirty. (There are thirty-seven in the series, and Jessy doesn’t leave things unfinished.) She’s read about witches, good and bad, about princesses and queens, about Polychrome the rainbow’s daughter, who’s particularly interesting to a colorist like Jessy. When she finishes a book she tells me the story, though as the plot dissolves in a jumble of details, my mind begins to wander. She enjoys the queens and witches, but what she uses is the information. When her interests turned from astrothings to real estate and banks, she was ready with what she’d learned from Oz. Banks lend money; Dorothy’s Auntie Em and Uncle Henry lost their farm in Kansas when they couldn’t pay the mortgage, and Auntie Em cried. Fortunate, then, that they could be transported to Oz, where, Jessy tells me, there isn’t any money. Out of fantasy Jessy plucks realism; in Oz there are magic trees, but hanging on them are lunch- boxes with ham sandwiches. In Oz she learns new words and concepts: «revenge» (tit for tat!), «enchantment», «oblivion».

Jessy has read about Willie Wonka and the chocolate factory, about James and the giant peach. But as with other autistic people, her primary interest is not in fiction but in fact. Oz is for vacations, when she has nothing else to do. But she scans every issue of The Harvard Health Letter, on the alert for items about drug side effects and the common cold. She checks out diseases in her medical encyclopedia. She reads the stories I’ve marked for her in the newspaper, her interests expanding from fees and ATM’s and accidents on Route 7 to hurricanes in the tropics and blizzards in South Dakota. That’s where the Ingallses had their problems, I remark, but Jessy supplies a nearer point of contact; her supervisor at work, an important person in her life, was stranded in South Dakota when the airport closed and has just got back. Maybe, Jessy suggests, we should send diapers and canned tuna fish to South Dakota; the news report says they are needed. So Jessy reads and thinks of others, as her world grows larger.

Like many for whom reading is hard and understanding partial, Jessy might be expected to prefer visual and auditory media. But it’s even harder for her to extract meaning from movies and TV. The rapid images and talk defeat her slow information processing; what she hears are her «transition phrases». She understands the maps on the Weather Channel better than I do, but the spoken explanations are only words. As for movies, the ones she likes are based on books she knows already. Though she doesn’t mine them for human relationships, insofar as they show her people in action they contribute their bit to Thinking of Others.

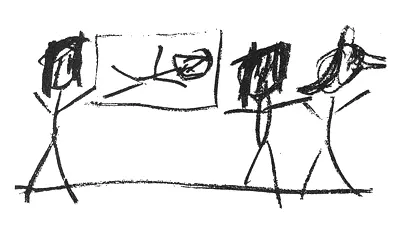

It would be natural to write here that as Jessy is more aware of others she is more aware of herself. Yet how she could be more aware of herself is hard for me to imagine. She drew a picture of herself before she could talk. [36] Reproduced in The Siege, 1982 and 2001 editions.

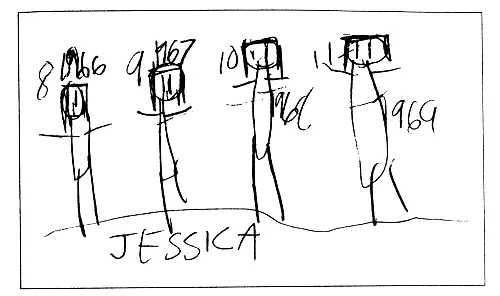

Among the Piper Cleaner people she placed herself as a major character. She even found a way to represent herself as their creator when she drew herself holding her drawing of Piper Cleaner Man. The picture with which she hailed her eleventh birthday is one of the treasures of the suitcase. JESSICA, she labeled it, in assertive capitals. It shows Jessy — Jessica at eight, at nine, at ten, at eleven: four Jessies, four years of progress. For each Jessy is taller than the last.

From left: Jessy (holding drawing of Piper Cleaner Man), Piper Cleaner Girl, Piper Cleaner Fairy, 1967

Jessy at different ages, drawn to mark her eleventh birthday, 1969

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)