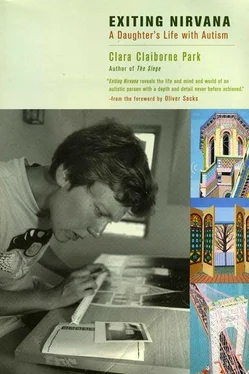

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Autistic refusal. It had been with her from the beginning, that hidden, withheld quality of so much she did and didn’t do, so that again and again we had to lure, almost trick, her into performing even activities that were clearly within her capabilities; so that again and again „couldn’t“ and „wouldn’t“ seemed indistinguishable. I had thought of that inertia as autism’s core, its deepest, most fundamental, most massive handicap.

I could scarcely believe, then, how shallow were its roots. The counter opened up an alternative explanation, less poetic than an existential refusal but closer to the facts of our experience. The contract worked because it showed Jessy exactly what to do and gave her a reason for doing it. The counter worked, with this child who counted before she could talk, for whom numbers possessed mysterious significance, because it provided for the first time a truly significant reward for effort. The tasks of development are hard; hard enough for normal children, harder for Jessy. She had not only to acquire ordinary self-help skills, but to surmount her communication handicap, to attend to speech and practice it, and to control her bizarre anxieties and the bizarre behavior that accompanied them. Why should she try to do these things? What motivates a child to grow?

Why even ask the question? Growth is „natural“, a child develops», its potentialities «unfold». The words themselves, in their root meanings, proclaim inevitability. We think about the process only when it fails to occur. But consider the child born to autism, able to understand unvarying shapes, routines, rules, but lacking the ability to interpret the constantly shifting, interlocking, mutually dependent appearances that make up the contexts in which human beings carry on their lives. Such a child will have no reason to master those hard developmental tasks. The normal child has strong social reasons to undertake them, to use the toilet like Daddy, to tie its shoes like Katy, to say words, elicit smiles, hugs, approval. Praise encourages it to do what comes naturally even to our cousins the apes, to imitate and join the life around it, to grow independent, to grow up. Children want to be like other people, and when they fail they are embarrassed or ashamed. But Jessy had no idea what it was to be like other people; she was as immune to embarrassment as she was to emulation. Praise had been meaningless to her; it came at her out of the inexplicable universe of what other people think and want. When praised she had tuned out, or worse, stopped the behavior that elicited it. Now, in her fifteenth year, it began to take on meaning — as a side effect of abstract numbers, of the mechanical reinforcement of a golf counter.

One Friday, after a year and a half of contracts, Jessy’s teacher called; she had something important to tell me. «Jessy and I have made a decision. Jessy’s not going to work for points anymore, she’s going to work for praise». And Jessy echoed, «Work for praise!» I was surprised at the suddenness of this unilateral decision, yet I understood it. The school had had nothing to do with administering the contract; Jessy had credited and debited herself, with the autistic, rule-bound exactitude that knows no possibility of cheating. But with her astonishing penchant for categorization, she had subdivided her list of behaviors, originally consisting of a few simple items, into a proliferating complexity ol subitems, and true to form was now in danger of occupying herself more with counting clicks than with the behaviors themselves. I had tried to «fade the prompts», to reduce the number of items — they now covered two full pages — but the system was Jessy’s, and it had taken on an autistic life of its own. Now I was told that Jessy and the teacher had decided to go cold turkey — no points, no contract. I didn’t think it would work; I anticipated a hellish weekend and a return to contract security, but I always support the teacher, and I said, «Fine».

But it did work. All the behaviors were maintained. Jessy kept on setting the table, taking out the trash, washing her underwear — all the simple, concrete acts that the contract had first rendered possible, then automatic. And of course with every one, we praised. We smiled, we hugged, we said, «Jessy, that’s good, that’s wonderful!» And after each instance Jessy, now smiling in open pleasure, chirped, «Is this praise? Is this praise?» The counter had taught her to enjoy praise, she had agreed to work for it, and she didn’t even know the meaning of the word. Mathematical abstractions might be obvious, but not this kind of abstraction — social, relational, taking all its meaning from human interaction. I recalled an earlier lesson the contract had taught not her but me: that Jessy had no idea what I meant when I included such items as Saying Something Interesting or Doing Something to Help. I’d learned to specify, say, six helpful behaviors, to define subjects of conversation that might conceivably be considered interesting. From those specifics Jessy could begin to grasp the social generalization, even, over the years, recognize new examples of the simple social category that practice had rendered familiar.

Behavior modification worked miraculously at the swimming pool, when there was no real resistance and only motivation was lacking. It worked miraculously with concrete actions that Jessy could understand, that she could do easily if she would. Doing Something to Help, for example, brought in a host of new activities. Jessy, it turned out, was perfectly willing to wash, to iron, to vacuum the whole house, and soon did it «without told». For things like these, the word «breakthrough» was entirely appropriate, and the gains were both permanent and significant. Every new occupation, after all, was an alternative to her sterile fallback activities, to sifting silly business or rocking.

In addressing the handicaps of autism, however, no break-throughs occurred. As the months passed and behaviors like Hitting and Screaming and Touching People’s Clothes remained on the contract, or more discouraging still, were dropped only to reappear weeks later, it became clear that behavior modification was a method, not a magic bullet, a method whose limitations were as significant as its powers. It was too much to imagine that complex social concepts could be built up piecemeal from a collection of imperfectly understood examples. Jessy was enthusiastic about doing a Big Job, Medium Job, or Little Job for a graded number of points. She could even understand how these translated into Something to Help. Doing Something Nice for Somebody, however, was not so accessible. It wasn’t easy to make niceness specific, considering how much individuals and circumstances differ. In social experience, we concluded, the contract could at most begin a process. The writing, the reading, the explanations, the repetitions, could introduce an idea and reinforce it. That was hardly miraculous, but it was worth doing. Though behavior modification couldn’t teach sensitive, imaginative, individualized moral responses, though Thinking of Others was years down the road, focusing on the possibilities of Doing Something Nice was a step forward.

Similarly, points and contracts only made a beginning in modifying autistic behaviors. Yet those behaviors were the greatest obstacles in her social habilitation. These were the things that disconcerted people, annoyed them, upset and bewildered them, frightened them, even on occasion disgusted them. Mumbling, rocking, making faces. Hitting, of course. Screaming. Crying. And the myriad instances of social unconsciousness: how could they be distinguished from deliberate rudeness? So Jessy must learn to notice things she had never noticed. She must try not to push aside people in her way; try not to walk between people who were talking to each other; try not to walk away when people were talking to her. These were the behaviors that brought many penalties and few rewards.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)