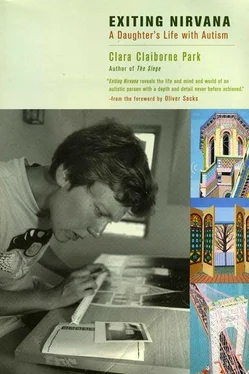

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We were walking together on the beach. It was windy and cold, and she decided to go up to the house for a sweatshirt. She came back wearing it, but there was something else over her arm. Her father’s jacket! Forty years of growing! It was worth the wait.

Charity begins at home, but there is more to thinking of others than thinking of your own family. Very early we provided a jar in the kitchen «for the poor children», and Jessy contributed her penny too. Poor children had no nice house, no good food, no Christmas tree. She must have taken some of that in, because it was many years before she could verbalize «others» that she made her book about the poor Indian family. But it was not until recently that her enthusiasm for weather phenomena propelled her beyond such unrealized generalities.

For days the big news on the Weather Channel was Hurricane Mitch. Jessy followed its course with interest; hurricanes can be classified, their changing strengths expressed in numbers. TV showed her Mitch’s results: mud slides and devastation in countries she’d never heard of, Nicaragua, Honduras. I marked the newspaper reports for her and she read them. «Honduras is one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere». «Over 6000 people died. Over a million lost their homes. Over 10, 000 were injured and over 5000 disappeared. Over 80 bridges were destroyed and countless roads are impassable». We went through our closets. Willingly Jessy took the bags to the collection point; spontaneously she applied her phrase, «That is thinking of others». At the benefit carol service, she was enthusiastic as she put her own five-dollar bill in the basket. She even used the word «charity», which I didn’t know she knew. (Still, she suggested next day that the people in Honduras could «evacuate», take a plane, a ship, to somewhere else, and had to be reminded they were too poor.)

There is personal altruism, and there is citizenship. Though I’ve worked hard on one, I’ve held back on the other. So I was surprised this year when amid vague talk concerning the next election Jessy informed me that the president can’t have a third term and that President Roosevelt had almost four. When on earth did she learn that? Then I remembered Marilyn, one of the most inspired of the Jessy-companions, tireless in thinking up activities Jessy could enjoy and interactions that could extend her social behavior. Marilyn must have told her. Jessy was already twenty-two when Marilyn lived with us. Ronald Reagan was running for president, and Marilyn thought Jessy should register to vote.

We didn’t think so. Much as we thought the country could use another vote against Reagan, it didn’t seem right it should come from Jessy, who barely knew he was alive and had no idea what he or any other president might do. Jessy remained unregistered.

Fast forward. We’re in the kitchen glued to the television, listening to the three-way debates of 1992, when suddenly Jessy pipes up, «You’re talking about the deficit!» Already interested in bank statements, she knew about deficits, and she didn’t like them. We’d also been talking about store closings; her sister had closed one of her shops, because of something called a recession. I showed her a report of another Main Street store closing something to read, something to expand awareness. I certainly wasn’t prepared for Jessy’s question: «Is it because of Bush?»

I attempt to explain that many factors go into a store closing, that it’s not the fault of just one person, even the president. But Jessy needs clear, definite answers; she’s already lost interest. Yet not altogether. Next day the local paper continues the story. Guess what! I read that about Newberry’s and it is because of Bush!

Shift forward again. Its 1999, and there’s not a deficit but a surplus. Jessy hasn’t noticed; she doesn’t know that word. Shall I tell her about it? She’d have no doubt whom to vote for. After so many years, is it time for Marilyn’s efforts to bear fruit?

I don’t know. Parents have their limits, and not just from aging. As her father couldn’t take her as far in math as she could go, so I don t know if I can, if I want to, if I should, propel Jessy into a citizen’s responsibility. Yes, she pays taxes, the concrete sign of it, and she understands at least some of the things that taxes go for. But can I take her to register, knowing her interest rides on the simplicity of an obsession— worse, that her vote would be no true choice but a mere echo of what we told her? Yet there are other single-issue voters, after all, and this issue is preferable to many I can think of. I don’t know. I just don’t know.

But I do know there’s progress, that Jessy’s still growing. That she’s not merely, passively, being taught, but taking in hand her own journey toward empathy, thinking about it, wording at it. Now, as I write, she is reviewing, confirming her social rules. Should she refuse when she’s asked to work overtime? «Only if I have another appointment, like giving blood. Because thinking of others is important». To think of others you have to notice how they feel. «I will learn by the voice when someone is irritated. Loud». Four days later: «I will remember how people feel when they get irritated. First the voice is loud and abrupt. But expression could be wrinkle face. Like frowning».

«Sometimes can tell when people are happy even if not smiling because can tell by the face. When people are happy eyes always glow and face shine like sun. And if people are sad face always looks gloomy like clouds. And between happy and sad like partly cloudy». Jessy said that twenty years ago, and joyfully I wrote it down. But did she say it or know it? Years went by and I heard nothing like it again. Maybe Joann told her that; maybe she only picked up on it because of sun and clouds. But now it’s spontaneous, now she’s noticing, now she’s focusing on those subtle indicators. Now she’s beginning to understand. When her load of magazines and catalogs breaks the janitor’s recycling bag, on her own she goes and gets him a new one. And she tells me, I felt so bad for that janitor! Let the millennium begin.

Chapter 10

«I guess Darth Vader learned from consequences! Like me!»

Inside the kitchen folder there is, not an envelope — an envelope’s not big enough — but another folder. It’s full and it grows fuller. It’s labeled Social. Its bulk is a reminder of what we slowly realized: that after the years of easy teaching, years of discovering the possibilities of what Jessy could learn, even excel at, there remained the wide expanse of things she could never excel at, that she could learn only partially and with the greatest difficulty.

Not that the teaching I now call easy ever felt easy. It was years before I got Jessy to feed herself; more years before she used the toilet. Even skills she had mastered, like climbing stairs, or marking with a crayon, or putting together a puzzle, would be lost and have to be introduced again. Teaching and maintaining the ordinary skills of childhood was a continual attempt to coax, to lure her past Kanner’s «obsessive desire for the maintenance of sameness» — past the barriers raised by her desire to continue what she was already doing, her contentment in remaining just where she was. Far more often than not the attempt was fruitless. I collected inspirational maxims to help me through the days — Nietzsche’s «What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger», or, after an especially hard week, the words of the Dutch liberator William the Silent: «It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake; it is not necessary to succeed in order to persevere».

In the midst of these years of mingled frustration and tedium, it’s not surprising that the few areas of Jessy’s clear, quick excellence took on a special importance. We used to say that the world was divided into things you couldn’t teach Jessy and things you didn’t have to teach her. That, of course, was an exaggeration. It might take eight years before she dressed herself completely, but eventually she did. Still, the contrast was striking between the things you must walk her through step by step, over and over, and the things you did not so much teach as show. Colors, shapes, letters (those too are shapes), numbers, later the system of musical notation — for such things her learning was so immediate it seemed we had merely drawn her attention to what she had always known. It was natural, then, that such achievements became for us lights shining in darkness — or, less melodramatically, signals, glimpsed through uncertain and shifting clouds. Peacock green and peacock blue, heptagons and dodecagons, factors and functions, were not merely welcome, they were thrilling. If Jessy couldn’t read — and at the height of her mathematical obsession she could read only three or four words together — if she couldn’t follow a story, we had these to hold on to, to marvel at and enjoy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)