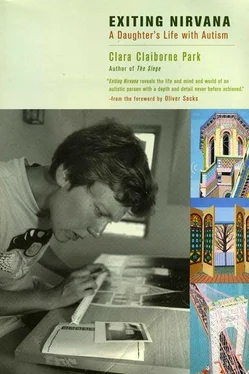

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As when, unexpectedly, we can’t go for our regular Saturday shopping. Daddy needs the car to visit his stepmother, a shut-in he hasn’t seen for months. Jessy, of course, is distressed, though now, mostly, she can control herself. This time there are no tears or screams, only the familiar, insistent questioning. If we can’t go to the supermarket, if we can’t get all the things on the list, what will happen?

I walk her through it. We do need a great many things, but we can get them at the downtown market. It becomes clear, however, that the particular items that Jessy has in mind, Stella D’oro cookies and Orville Redenbacher popcorn, are not available downtown. Considerable talk, then, about this, as I present the possibilities: we can do without cookies, we can do without popcorn, we can buy another brand. Jessy acknowledges these alternatives, which she knows well enough. Reluctantly, repetitively, she acquiesces. But that is not the end of the process. Finally, she repeats to herself (in question form, but she knows the answer) the correct priorities: «Is it more important to go see Winifred than to get popcorn and Stella D’oro?» I have, of course, spent the last half hour telling her exactly that, that Winifred is lonely, that she hasn’t seen Daddy for months. Though her question is «rhetorical», I answer, «Yes». And Jessy is now ready to affirm the principle no normal seven-year-old needs to have made explicit: It is more important to go see a shut-in relative than to get popcorn.

Jessy was nearing twenty when one of the young companions set her a new goal. Taking a sheet of paper, Joann wrote at the head of it, THINKING OF OTHERS. She helped Jessy think of a few things that might consist of. They listed them. The formal layout helped focus Jessy’s attention; the examples gave the social abstraction specific, concrete meanings. Jessy has spent the ensuing twenty years extending those meanings into something that may be called a general concept.

At first it was a behavioral category, its instances specified and rewarded. Then, as Jessy got the idea, she began to come up with her own examples. Not that she had miraculously acquired insight into other people’s feelings; you still had to — still have to — tell her you are sad, and her ritualized «I hope you will feel better» is not really very comforting. Thinking of Others remained touchingly concrete: «I put nutmeg instead of cinnamon in the pudding because I know you don’t like that». She told us she didn’t need us to make an Easter egg hunt for her anymore — but she made one for us. When two good friends came to visit she put two lollipops and two Nabisco wafers by their bed, bought with her own money. She even began to connect her own experience with other people’s; remembering when she lost her wallet, she could reflect, «If I find a wallet with identification I will call that number and ‘I found a wallet’ and that person will be so relieved!» The situation was hypothetical, but the attribution of feelings, even the adjective, was correct.

Thinking of others, of course, is hard when you don’t have a «theory of mind» to allow you to see something from another point of view. Even in the unemotional, physical world, Jessy can’t do this. She locks the door behind her when she leaves for work, even though she knows I’m still inside and there’s no need to. She scrapes the ice off the windshield on the passenger’s side, her side, leaving the driver’s side obscured. She thinks I can see what she sees; if she knows something, she thinks the person she’s talking to knows it too. We are back in chapter 3, with the Sally- Anne test. For years we wondered; now we know that in autism it is the cognitive, not the emotional, handicap that is primary.

Nevertheless, in social life it is the emotional that is salient. It is that handicap, that lack, that we notice first, that troubles us most as we try to communicate to our autistic child, as we did to our other children, that extraordinary triumph of thought and feeling we call the Golden Rule. «How would you feel», we asked them, if Tommy hit you, grabbed your cookie, told you he hated you? Clever George Bernard Shaw said not to do unto others as you would have them do unto you because tastes differ. But even that iconoclastic reversal recognizes the rule’s emotional core, as the fact that we call it a rule recognizes its cognitive, generalizable element. But by whatever combination of rational and emotive we ourselves understand — and feel — it best, whether we elevate it to a religious principle or reduce it to simple good manners, whether we honor it in the breach or not at all, it is the foundation of civilized social life.

Jessy was late into her teens before it made any sense to try her on «How would you feel if». And even then her own translation reveals what she made of it: «Tit for tat».

It was my own failure of imagination. Of course I’d learned that I couldn’t rely on words alone to reach Jessy’s understanding; I had to illustrate any new idea through action. Unfortunately it is far easier to illustrate Socrates’ negative formulation of the rule than Jesus’ positive one. I do something nice for you. It feels good. That’s how people feel when you do something nice for them. You want them to feel good, don’t you? Even to me it doesn’t sound compelling. The Socratic version is more immediate: Don’t do unto others as you wouldn’t have them do unto you. Maybe Tommy did hit you, but don’t hit him back.

But with no convenient Tommy at hand, the best I could think of was, I fear, the worst. There were plenty of things Jessy did unto others that she wouldn’t like done to her. She snapped. She hit — not hard, but she did. She even came at one good friend with a rake. All I could think of was to do the same thing to her, as far as possible in exactly the same way. Jessy didn’t like loud, sudden noises. She certainly didn’t like being hit. Nobody had ever come after her with a rake, but if they had, she might have been frightened but her feelings wouldn’t have been hurt. Socrates’ rule brought her no nearer to understanding why her friend Tracy never came back. It’s not surprising she made it into tit for tat, and experienced it not as teaching but as punishment. Only the capacity to imagine other people’s feelings can distinguish tit for tat from the Golden Rule, the Old Law from the New. And it’s not enough to imagine them; you have to put them before your own. That’s hard enough for normal human beings.

Nevertheless, slowly, slowly, it begins to happen, even for Jessy, even through tit for tat. «Why aren’t you unpacking the groceries?» Jessy asks angrily. «Why aren’t you helping in the garden?» I reply, and she understands. Or we arrange to feed her brother’s cats for four days: he will come stay with her when we go away. You help me, I help you, is fair exchange. How many people never get any farther?

But Jessy is going farther. Now she spontaneously verbalizes the principle Joann taught her half her life ago. Someone gives her a book about insects. It has a scorpion on the cover, and Jessy is interested in the story I tell her, that when her brother was a baby in Ceylon a scorpion almost bit him but we killed it. Her busy mind works it over. «So if a scorpion had bit him, then would have no brother». Pause. «And that’s a good reason to cry even if it [makes you] exposed to cold». And then, astonishingly, «Because it’s better to feel sick than selfish».

It’s a highly hypothetical outcome for a healthy brother in his midforties. I’m even more joyful when principle leads to action. Last year she put the cat’s water bowl outside the bathroom when she took her shower. It wasn’t pure altruism, for she did not want to hear Daisy scratching at the door. Still, by her lights she had earned the right to say, as she did, «That is thinking of others». But this year — I was already working on this book — she thought, not of Daisy’s comfort, but really, truly, genuinely, of her father’s.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)