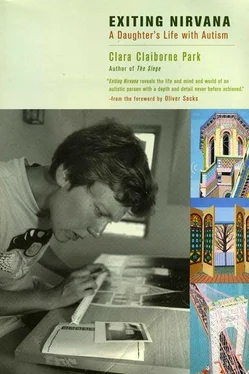

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As time went on and self-awareness could move from pictures to speech, she noted other kinds of growth. «I can’t believe it, I read without being coaxed!» «I’m getting better at not insult- mg people» (her truthfulness compelled her to add, «Only did that last week»). «I had a speech handicap a long time ago». Who would correct such a comfortable assessment? Jessy’s self-awareness usually is weighted toward the positive. She knows how sharp her hearing is, and often refers to it; she knows she has a remarkable sense of color. She is not at all surprised to find a story about herself in the paper. «Daddy found another announcement of my show!» Her smile is not an autistic, why-are- you-smiling smile; it is the smile of justified self-satisfaction.

Jessy is aware of her abilities and her progress. More surprising, in view of her incomprehension of other people’s thoughts and feelings, is her awareness of her own mind. Mind, of course, is a highly abstract concept, and Jessy was sixteen when she first used the word. But she used it with an understanding that suggested the idea was not new to her. Looking at an old drawing of a tunnel in which her superball went «back and forth, back and forth», she told me where it happened — not in a real tunnel, but «in my mind». From then on it was a phrase she used freely; it allowed her to verbalize the difference she’d always recognized between the reality outside and the imaginary within.

Her self-awareness, of course, is intensified as I enlist her memories for this book. But even I am astonished by her consciousness of her mental history. Though I’ve asked her many questions, I never asked her where her wee-alo’s came from; it didn’t occur to me that she knew. So a few months ago I heard their origin for the first time: «I got that wee-alo’s from the hellos at the end of the sentence» — the hellos that were extinguished a quarter-century ago. If she’s aware of that, what else may she know?

She’s aware of her dreams, too; if asked she will write them down. Often she illustrates them, and indeed they recall her earlier comic books. The plots, insofar as they exist, are sequential; there are no «dreamlike» discontinuities. They have generally upbeat endings. They are matter-of-fact even in fantasy. And they display plenty of «I».

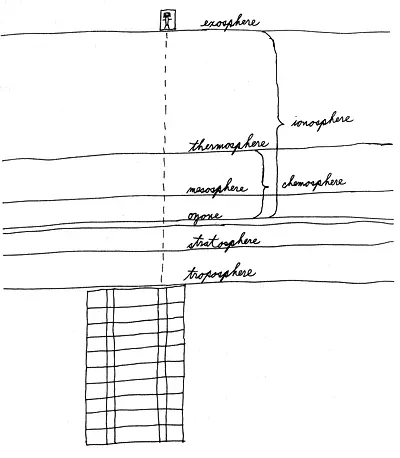

First I went downstairs with the elevator to see some beautiful things. Then I went up to 8th floor. I waited for another elevator for 10th floor. It came and I went high into space. I said, «Come back elevator. I am lost in atmosphere. „I saw the top of this building and came [back] to the 10th floor“».

Another, somewhat simpler:

I watched many cartoon movies about the swing set made of trees. Bears and other animals climbed onto it.

Another:

I’m sick and tired of living on Hoxsey Street. I’m moving to Washington. I’m going to live in a friend’s house.

Like her comic books, her dreams are derivative rather than imaginative. Jessy drew the «swing set»; hung between trees, it was recognizably the swing of her childhood. The animals are out of television. The vocabulary of her trip in space — her drawing of the dream had labels like «troposphere», «stratosphere», «mesosphere» — came from a scientific picture book. A friend once talked of a summer in Washington. Only the most hardened Freudian could convert such externalities into symbols. There is something uncanny about a dream life so unmysterious, so close to the life of waking. But it is certainly self-aware.

The elevator dream

Jessy is aware of herself, but there is a gap in her awareness. She is far more conscious of herself cognitively than emotionally. Mind — the word and the concept — came long before heart, though once she learned that hearts were something more than valentines or anatomical features they became a favorite topic. «I can’t believe it, there are many ways to say ‘-hearted’! There’s ‘lighthearted,’ ‘heavyhearted,’ ‘downhearted,’ ‘brokenhearted,’ ‘chickenhearted,’ ‘lionhearted,’ ‘stouthearted,’ ‘good-hearted’!» It is possible to talk about emotions autistically; what these terms might actually mean is lost in the pleasing formalism. Encouraged to talk about «emotional feelings», Jessy readily adopts the new word, only recently distinguished from «motion» and still tinged with its meaning. Motion, moving. «I always walk fast if I’m happy and slow if I’m sad. Because of emotional feelings». She finds this worth thinking about, for next day, all smiles, she has more to add. «This is another reason about the emotional feelings. If my heart is light I can walk fast, if my heart is heavy I can walk slow. Because my feet will be heavy if I feel sad». Yet affairs of the heart, if you don’t understand them, aren’t really very interesting. Complacently, but only briefly, Jessy considers herself as an emotional being: «Boy, I never fell in love, with male or female!»

Jessy is not more self-aware as she begins to see herself in relation to others, but she is aware of herself differently. The selfinvolvement of autism diminishes, with obvious advantages. But with that comes — or might come — a source of pain. Does Jessy know she’s different? It’s a natural question; many people ask it. The answer is more complex than a simple yes or no, or even the «not yet» I put down when I first wrote about it almost twenty years ago. [37] C. C. Park, „Growing Out of Autism“, in Autism in Adolescents and Adults, E. Schopler and G. B. Mesibov, eds. (New York: Plenum, 1983), p. 294.

It trails with it another, less natural question: not does she know, but does she care? What does autism — what does a mental handicap — mean to her?

Jessy was twenty-seven when an auto accident got us talking about the benefits of seat belts. I mentioned a child I knew of who had suffered brain damage in an accident before seat belts became mandatory. Jessy, showing some of her medical knowledge, at once picked up on the words «brain damage»; it could, she said, make you paralyzed. I said it could also make you retarded (as had indeed happened), so that you couldn’t think very well or have a job. I could not have predicted Jessy’s reaction. It was better to die in the accident, she said, than be — paralyzed, I expected, but instead she said «retarded». «Because then I couldn’t have a good life». Clearly she had some idea of what it meant to be retarded — I suppose she’d heard the word at school. But just as clearly, her nine years in the special class had never suggested to her that it might be applied to herself.

To Jessy, handicaps are physical. A mental handicap is a perfect example of the kind of social generalization her mind has difficulty forming. She knows she took a long time to learn to talk and that she has to work hard to control her behavior — harder than other people. That’s the way we’ve presented her difference to her. But the comparison is ours, not hers. To feel your own difference you have to form a concept of what other people are like, how they live, what’s expected of them.

We had never tried to suppress the word «autistic», either in conversation or as it appeared in various publications about the house. Jessy had never asked about it. She knew there was a book about her; she had even typed the Spanish translation. There were no books about her siblings. She didn’t wonder why; social comparisons were not within her scope. If she was to know she was autistic, we would have to tell her. The years went by and we didn’t. She knew her problems; she went over them every day with her imagery scenes. It didn’t seem necessary to give them a name.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)