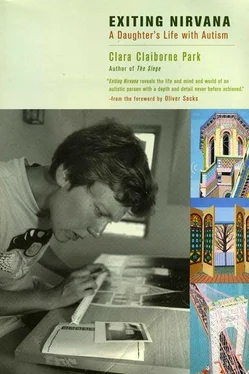

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then, in 1988, Rain Man came along. That extraordinary movie made people in America and all over the world aware of a handicap few had known existed. We saw it and marveled at its accuracy and sensitivity. To prepare for his role Dustin Hoffman had spent weeks with two autistic young men — one was Joe Sullivan, whose multiplications and primes were so like Jessy’s. Hoffman had absorbed the mumbles, the gait, the postures, the characteristic preoccupations of autism. He had sought expert advice; the film’s credits were an honor roll of autism. Here was our opportunity. Jessy was thirty. Should we take her to see it?

We did. She saw it twice. It was the first adult movie — and so far the last — that she really enjoyed and understood. She recognized Rain Man’s obsessions. «He was inflexible about his underwear», she told her brother. «And he stared at the dryer, clothes going round and round». He said «I don’t know» a lot. He liked Wheel of Fortune. He mumbled. She could relate to it all, even feel a bit superior. «And he also farted in the telephone booth, and his brother said a bad word, a horrendous verbalization». She wouldn’t do that — though her brother probably would. Jessy has known she is autistic ever since.

Many autistic adults greet their diagnosis with relief. It explains their problems; it may even put them in touch with others like themselves. But they are less severely affected than Jessy; they feel and understand things she does not. For Jessy autism is not a difficult social condition but a collection of specifics — mumbling, crying, staring at things that go round and round. But those specifics have led her forward; out of her awareness of autism have come her first social generalizations.

«Well, I haven’t cried for a whole month», she remarks. «Just like the other adults». Then she adds, «I know some of the other autistic people cried». Like other adults, like other autistic people. Two comparisons — herself as normal (a word she has never used), herself as autistic. Taking it further: «If I cry I always make faces. If when people cry do they always make faces?» She’s thinking it through; she knows they don’t. Later she will even say, after one of her now rare mumbles, «Mother, I can’t help it because I’m one of the autisms». The generalization achieved, Jessy has placed herself within it. But the odd diction gives her away. Autism is a plural.

It is also a fact. Jessy takes it behavior by behavior, which is probably the best way. Certainly it saves her a great deal of pain. She doesn’t suffer because she has no boyfriend. She doesn’t yearn for a baby. She has never asked why she is autistic, why, in the searing words of one child, «God made me be like this. Jessy knows who she is, and though she may wish she’d behaved differently in one case or another, she shows no sign of wanting to be anything but what she is.

And yet, in the light of her awareness of her „autisms“, she now is able to say that she’s ashamed. What are we to make of that?

Some cynic defined conscience as the little voice inside us that tells us that someone is looking. His joke was deliberately to confound inside with outside, conscience with shame. Our civilization tends to prefer conscience, to respect actions that arise from interior conviction above actions performed — or avoided — because of „what people will think“. The parents of an autistic person, however, have a harder time admiring indifference to other people’s opinions. Our child may not notice the stares and comments, but we do. And though we may be angry and inveigh against society’s insensitivity, we begin to see the advantages of shame, and agree with Homer, who long ago said that it „does much harm to people but profits them also“. For a person who doesn’t care about what people think of her, one of the most effective human motivators is absent. If Jessy can say she is ashamed, if she experiences that bad feeling so familiar to most of us, if it hurts, if it makes her unhappy, surely it’s to be welcomed as a huge step forward, an entrance into a new awareness of herself in society. If she can add actual real-world embarrassment to her STOP and RELAX and imagined rewards, mustn’t their power be doubled?

Jessy says she’s ashamed after she’s done something egregious, like angrily snapping at an innocent what-question. It happens, though she’s rehearsed her what-scenes more times than I could count. „What are you doing?“ someone asked her not so long ago. He was a cameraman, and he needed to know. The words came at him like bullets: „Why do you ask me that?!“ Then she whimpered, then she cried a bit, then she said, „I’m ashamed“. So he caught on film what must, if we take it at face value, demonstrate exactly that concern for how she appears to others I’ve insisted is missing. [38] The whole episode can be seen in „Rage for Order“, the hour-long section on autism from the BBC’s series on Dr. Oliver Sacks, The Mind Traveller, shown in 1996 on PBS (Rosetta Pictures for the British Broadcasting Company, directed by Christopher Rawlence).

But those who know Jessy learn that the words she uses, even when they appear to suit the circumstances, do not always mean what they mean for us. The episode needs some digging; there is more to the story.

The innocent cameraman (of course he felt terrible about it) was part of a documentary team. They had been following us around for five days, guided by Dr. Oliver Sacks, and everything had gone more than well. They were shooting a six-part series on Dr. Sacks; Jessy was the center of attention of the autism section. She was filmed with her paintings, with an ATM machine, with the old sheets of flavor tubes. She was taken for a ride on her favorite routes. She loved it all. But then she snapped.

They got it on camera, and Jessy knew it. She knew that people would see it. And clearly, unambiguously, she said she didn’t want it in the film. It wasn’t the first time she’d said she was ashamed. But she’d never before said anything like that.

Of course they told her that if she didn’t want it they wouldn’t put it in. Months later, however, as the director, Christopher Rawlence, was putting together the footage, he realized that he needed Jessy’s snap. To present autism as all charm and interesting strangeness was to romanticize it past recognition. We read Chris’s letter to Jessy: though of course he would keep his promise to her, would she perhaps be willing to let him show her snapping, and crying, and being sorry? She said yes without a qualm — it was past, it was over, whatever she’d felt, whether embarrassment, shame, or simply the bad feeling that comes with disapproval. The snap went into the picture; it has been seen on both sides of the Atlantic. Chris sent us a video, and Jessy has watched it many times. She likes the route signs and the ATM. But the snap is her favorite part. She doesn’t wince; she doesn't turn away. „I didn’t know it was so loud!“ she says — smiling.

I would like to think that the story of that snap contains some glint of a more fully social, more conscious future. But it pulls both ways; I don’t know. This book will be long finished before I find out.

I do know, however, that the vocabulary of handicap doesn’t work for Jessy. She doesn’t „suffer from“ autism. She doesn’t think of herself as handicapped. „Afflicted“ is a word she doesn’t know. As in other things, she’s matter-of-fact. She’s well aware of her obsessions, whether she calls them enthusiasms or whether she calls them autisms and they get her into trouble. She’s aware of her compulsions and rigidities and routines. She knows she must control them if she’s to avoid… shame, perhaps, but certainly unpleasant consequences. She knows she needs consequences to do this, and imagery scenes, and what we call, and she calls, Flexibility Practice. She knows how important flexibility is to her daily life, and to what is perhaps its most important social element, her job.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)