So far, we’ve explored what individuals can do to maximize their success on the job market in the age of AI. But what can governments do to help their workforces succeed? For example, what education system best prepares people for a job market where AI keeps improving rapidly? Is it still our current model with one or two decades of education followed by four decades of specialized work? Or is it better to switch to a system where people work for a few years, then go back to school for a year, then work for a few more years?50 Or should continuing education (perhaps provided online) be a standard part of any job?

And what economic policies are most helpful for creating good new jobs? Andrew McAfee argues that there are many policies that are likely to help, including investing heavily in research, education and infrastructure, facilitating migration and incentivizing entrepreneurship. He feels that “the Econ 101 playbook is clear, but is not being followed,” at least not in the United States.51

Will Humans Eventually Become Unemployable?

If AI keeps improving, automating ever more jobs, what will happen? Many people are job optimists, arguing that the automated jobs will be replaced by new ones that are even better. After all, that’s what’s always happened before, ever since Luddites worried about technological unemployment during the Industrial Revolution.

Others, however, are job pessimists and argue that this time is different, and that an ever-larger number of people will become not only unemployed, but unemployable.52 The job pessimists argue that the free market sets salaries based on supply and demand, and that a growing supply of cheap machine labor will eventually depress human salaries far below the cost of living. Since the market salary for a job is the hourly cost of whoever or whatever will perform it most cheaply, salaries have historically dropped whenever it became possible to outsource a particular occupation to a lower-income country or to a cheap machine. During the Industrial Revolution, we started figuring out how to replace our muscles with machines, and people shifted into better-paying jobs where they used their minds more. Blue-collar jobs were replaced by white-collar jobs. Now we’re gradually figuring out how to replace our minds by machines. If we ultimately succeed in this, then what jobs are left for us?

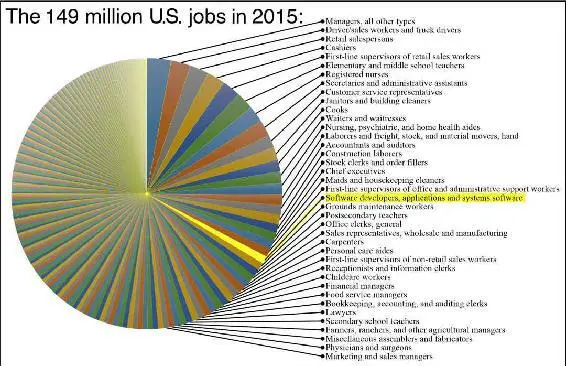

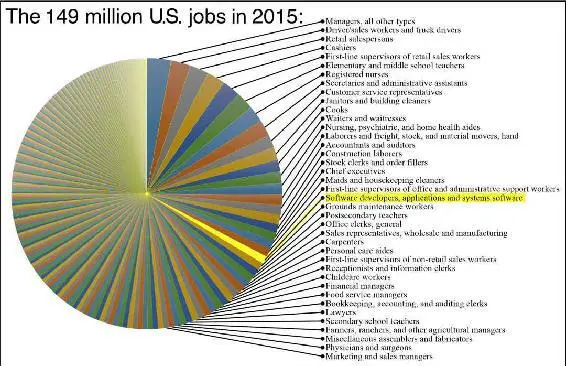

Some job optimists argue that after physical and mental jobs, the next boom will be in creative jobs, but job pessimists counter that creativity is just another mental process, so that it too will eventually be mastered by AI. Other job optimists hope that the next boom will instead be in new technology-enabled professions that we haven’t even thought of yet. After all, who during the Industrial Revolution would have imagined that their descendants would one day work as web designers and Uber drivers? But job pessimists counter that this is wishful thinking with little support from empirical data. They point out that we could have made the same argument a century ago, before the computer revolution, and predicted that most of today’s professions would be new and previously unimagined technology-enabled ones that didn’t use to exist. This prediction would have been an epic failure, as illustrated in figure 3.6: the vast majority of today’s occupations are ones that already existed a century ago, and when we sort them by the number of jobs they provide, we have to go all the way down to twenty-first place in the list until we encounter a new occupation: software developers, who make up less than 1% of the U.S. job market.

We can get a better understanding of what’s happening by recalling chapter 2, which showed the landscape of human intelligence, with elevation representing how hard it is for machines to perform various tasks and the rising sea level showing what machines can currently do. The main trend on the job market isn’t that we’re moving into entirely new professions. Rather, we’re crowding into those pieces of terrain in figure 2.2 that haven’t yet been submerged by the rising tide of technology! Figure 3.6 shows that this forms not a single island but a complex archipelago, with islets and atolls corresponding to all the valuable things that machines still can’t do as cheaply as humans can. This includes not only high-tech professions such as software development, but also a panoply of low-tech jobs leveraging our superior dexterity and social skills, ranging from massage therapy to acting. Might AI eclipse us at intellectual tasks so rapidly that the last remaining jobs will be in that low-tech category? A friend of mine recently joked with me that perhaps the very last profession will be the very first profession: prostitution. But then he mentioned this to a Japanese roboticist, who protested: “No, robots are very good at those things!”

Figure 3.6: The pie chart shows the occupations of the 149 million Americans who had a job in 2015, with the 535 job categories from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics sorted by popularity.53 All occupations with more than a million workers are labeled. There are no new occupations created by computer technology until twenty-first place. This figure is inspired by an analysis from Federico Pistono.54

Job pessimists contend that the endpoint is obvious: the whole archipelago will get submerged, and there will be no jobs left that humans can do more cheaply than machines. In his 2007 book Farewell to Alms, the Scottish-American economist Gregory Clark points out that we can learn a thing or two about our future job prospects by comparing notes with our equine friends. Imagine two horses looking at an early automobile in the year 1900 and pondering their future.

“I’m worried about technological unemployment.”

“Neigh, neigh, don’t be a Luddite: our ancestors said the same thing when steam engines took our industry jobs and trains took our jobs pulling stage coaches. But we have more jobs than ever today, and they’re better too: I’d much rather pull a light carriage through town than spend all day walking in circles to power a stupid mine-shaft pump.”

“But what if this internal combustion engine thing really takes off?”

“I’m sure there’ll be new new jobs for horses that we haven’t yet imagined. That’s what’s always happened before, like with the invention of the wheel and the plow.”

Alas, those not-yet-imagined new jobs for horses never arrived. No-longer-needed horses were slaughtered and not replaced, causing the U.S. equine population to collapse from about 26 million in 1915 to about 3 million in 1960.55 As mechanical muscles made horses redundant, will mechanical minds do the same to humans?

Giving People Income Without Jobs

So who’s right: those who say automated jobs will be replaced by better ones or those who say most humans will end up unemployable? If AI progress continues unabated, then both sides might be right: one in the short term and the other in the long term. But although people often discuss the disappearance of jobs with doom-and-gloom connotations, it doesn’t have to be a bad thing! Luddites obsessed about particular jobs, neglecting the possibility that other jobs might provide the same social value. Analogously, perhaps those who obsess about jobs today are being too narrow-minded: we want jobs because they can provide us with income and purpose, but given the opulence of resources produced by machines, it should be possible to find alternative ways of providing both the income and the purpose without jobs. Something similar ended up happening in the equine story, which didn’t end with all horses going extinct. Instead, the number of horses has more than tripled since 1960, as they were protected by an equine social-welfare system of sorts: even though they couldn’t pay their own bills, people decided to take care of horses, keeping them around for fun, sport and companionship. Can we similarly take care of our fellow humans in need?

Читать дальше