Technology and Inequality

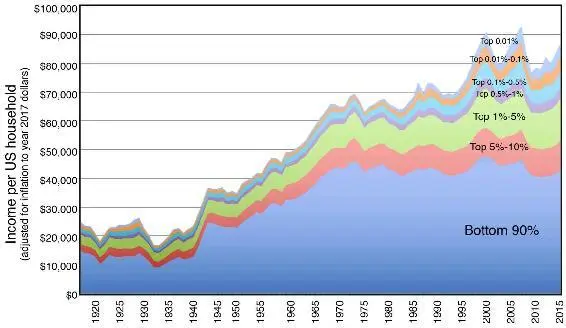

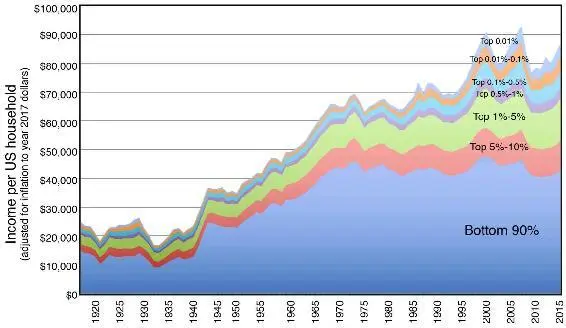

We can get from where we are today to Erik’s Digital Athens if everyone’s hourly salary keeps growing year by year, so that those who want more leisure can gradually work less while continuing to improve their standard of living. Figure 3.5 shows that this is precisely what happened in the United States from World War II until the mid-1970s: although there was income inequality, the total size of the pie grew in such a way that almost everybody got a larger slice. But then, as Erik is the first to admit, something changed: figure 3.5 shows that although the economy kept growing and raising the average income, the gains over the past four decades went to the wealthiest, mostly to the top 1%, while the poorest 90% saw their incomes stagnate. The resulting growth in inequality is even more evident if we look not at income but at wealth. For the bottom 90% of U.S. households, the average net worth was about $85,000 in 2012—the same as twenty-five years earlier—while the top 1% more than doubled their inflation-adjusted wealth during that period, to $14 million.42 Differences are even more extreme internationally where, in 2013, the combined wealth of the bottom half of the world’s population (over 3.6 billion people) is the same as that of the world’s eight richest people43—a statistic that highlights the poverty and vulnerability at the bottom as much as the wealth at the top. At our 2015 Puerto Rico conference, Erik told the assembled AI researchers that he thought progress in AI and automation would continue making the economic pie bigger, but that there’s no economic law that everyone, or even most people, will benefit.

Although there’s broad agreement among economists that inequality is rising, there’s an interesting controversy about why and whether the trend will continue. Debaters on the left side of the political spectrum often argue that the main cause is globalization and/or economic policies such as tax cuts for the rich. But Erik Brynjolfsson and his MIT collaborator Andrew McAfee argue that the main cause is something else: technology.44 Specifically, they argue that digital technology drives inequality in three different ways.

First, by replacing old jobs with ones requiring more skills, technology has rewarded the educated: since the mid-1970s, salaries rose about 25% for those with graduate degrees while the average high school dropout took a 30% pay cut.45

Second, they claim that since the year 2000, an ever-larger share of corporate income has gone to those who own the companies as opposed to those who work there—and that as long as automation continues, we should expect those who own the machines to take a growing fraction of the pie. This edge of capital over labor may be particularly important for the growing digital economy, which tech visionary Nicholas Negroponte defines as moving bits, not atoms. Now that everything from books to movies and tax preparation tools has gone digital, additional copies can be sold worldwide at essentially zero cost, without hiring additional employees. This allows most of the revenue to go to investors rather than workers, and helps explain why, even though the combined revenues of Detroit’s “Big 3” (GM, Ford and Chrysler) in 1990 were almost identical to those of Silicon Valley’s “Big 3” (Google, Apple, Facebook) in 2014, the latter had nine times fewer employees and were worth thirty times more on the stock market.47

Figure 3.5: How the economy has grown average income over the past century, and what fraction of this income has gone to different groups. Before the 1970s, rich and poor are seen to all be getting better off in lockstep, after which most of the gains have gone to the top 1% while the bottom 90% have on average gained close to nothing.46 The amounts have been inflation-corrected to year-2017 dollars.

Third, Erik and collaborators argue that the digital economy often benefits superstars over everyone else. Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling became the first writer to join the billionaire club, and she got much richer than Shakespeare because her stories could be transmitted in the form of text, movies and games to billions of people at very low cost. Similarly, Scott Cook made a billion on the TurboTax tax preparation software, which, unlike human tax preparers, can be sold as a download. Since most people are willing to pay little or nothing for the tenth-best tax-preparation software, there’s room in the marketplace for only a modest number of superstars. This means that if all the world’s parents advise their kids to become the next J. K. Rowling, Gisele Bündchen, Matt Damon, Cristiano Ronaldo, Oprah Winfrey or Elon Musk, almost none of their kids will find this a viable career strategy.

Career Advice for Kids

So what career advice should we give our kids? I’m encouraging mine to go into professions that machines are currently bad at, and therefore seem unlikely to get automated in the near future. Recent forecasts for when various jobs will get taken over by machines identify several useful questions to ask about a career before deciding to educate oneself for it.48 For example:

• Does it require interacting with people and using social intelligence?

• Does it involve creativity and coming up with clever solutions?

• Does it require working in an unpredictable environment?

The more of these questions you can answer with a yes, the better your career choice is likely to be. This means that relatively safe bets include becoming a teacher, nurse, doctor, dentist, scientist, entrepreneur, programmer, engineer, lawyer, social worker, clergy member, artist, hairdresser or massage therapist.

In contrast, jobs that involve highly repetitive or structured actions in a predictable setting aren’t likely to last long before getting automated away. Computers and industrial robots took over the simplest such jobs long ago, and improving technology is in the process of eliminating many more, from telemarketers to warehouse workers, cashiers, train operators, bakers and line cooks.49 Drivers of trucks, buses, taxis and Uber/Lyft cars are likely to follow soon. There are many more professions (including paralegals, credit analysts, loan officers, bookkeepers and tax accountants) that, although they aren’t on the endangered list for full extinction, are getting most of their tasks automated and therefore demand many fewer humans.

But staying clear of automation isn’t the only career challenge. In this global digital age, aiming to become a professional writer, filmmaker, actor, athlete or fashion designer is risky for another reason: although people in these professions won’t get serious competition from machines anytime soon, they’ll get increasingly brutal competition from other humans around the globe according to the aforementioned superstar theory, and very few will succeed.

In many cases, it would be too myopic and crude to give career advice at the level of whole fields: there are many jobs that won’t get entirely eliminated, but which will see many of their tasks automated. For example, if you go into medicine, don’t be the radiologist who analyzes the medical images and gets replaced by IBM’s Watson, but the doctor who orders the radiology analysis, discusses the results with the patient, and decides on the treatment plan. If you go into finance, don’t be the “quant” who applies algorithms to the data and gets replaced by software, but the fund manager who uses the quantitative analysis results to make strategic investment decisions. If you go into law, don’t be the paralegal who reviews thousands of documents for the discovery phase and gets automated away, but the attorney who counsels the client and presents the case in court.

Читать дальше