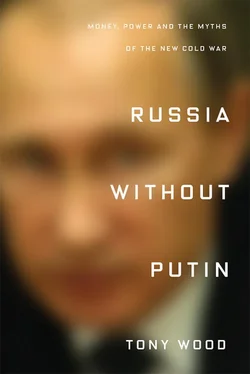

Tony Wood - Russia Without Putin - Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tony Wood - Russia Without Putin - Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Verso Books, Жанр: Политика, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War

- Автор:

- Издательство:Verso Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-78873-124-9

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

It is impossible to think of Russia today without thinking of Vladimir Putin. More than any other major national leader, he personifies his country in the eyes of the outside world, and dominates Western media coverage of it to an extraordinary extent. In Russia itself, he is likewise the centre of attention for detractors and supporters alike. But as Tony Wood argues, this overwhelming focus on the president and his personality means that we understand Russia less than we ever did before. Too much attention is paid to the man, and not enough to the country outside the Kremlin’s walls.

In this timely and provocative analysis, Wood looks beyond Putin to explore the profound changes Russia has undergone since 1991. In the process, he challenges many of the common assumptions made about contemporary Russia. Though commonly viewed as an ominous return to Soviet authoritarianism, Putin’s rule should instead be seen as a direct continuation of Yeltsin’s in the 1990s. And though many of Russia’s problems today are blamed on legacies of the Soviet past, Wood argues that the core features of Putinism – a predatory, authoritarian elite presiding over a vastly unequal society – are integral to the system set in place after the fall of Communism.

What kind of country has emerged from Russia’s post-Soviet transformations, and where might it go in future? Russia Without Putin culminates in an arresting analysis of the country’s foreign policy – identifying the real power dynamics behind its escalating clashes with the West – and with reflections on the paths Russia might take in the 21st century.