Robert Moore

KURSK

Putin’s First Crisis and the Russian Navy’s Darkest Hour

To the crew of K-141 and the extraordinary families they left behind, especially the seventy children

And to Liz, Timothy, Freya and Claudia for their inspiration

‘Of all the branches of men in the forces there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.’

– WINSTON CHURCHILL

On 12 August each year, at Russian naval bases from Vladivostok to Kaliningrad and from Murmansk to Sevastopol, and aboard ships of all four Fleets, officers and recruits stand at attention and observe a moment of silence. In many garrisons, an Orthodox priest leads a short memorial service, with incense floating in the summer air, and a melodic chant audible across the parade ground. The blue and white Andreyev flag of the Russian Navy flies at half-staff.

Entirely out of view, below the surface of Russia’s seas and beyond, the sailors of the submarine flotillas also pause at their posts to remember lost comrades.

The most poignant memorial service takes place in St Petersburg, the magnificent Baltic port that has been the spiritual home of the Russian Navy since the city’s founding in 1703. At the Serafmovskoye cemetery, families hold each other for comfort. Children gather around the graves of fathers they never knew or can barely remember. Widows and mothers place red roses beside the headstones. The graveyard is best known as the burial site for the countless thousands who died of cold and starvation in the Great Siege of Leningrad of 1941, but it also holds other patriots and military heroes from the nation’s tumultuous past.

This is the final resting place for thirty-two sailors of the Kursk , who boarded their submarine on a calm midsummer’s day in 2000 for a short training exercise in Arctic waters and who never again saw the Russian Motherland. Among those buried here is the commanding officer of the submarine, Captain Gennady Lyachin. Each headstone has a portrait of the sailor etched into black marble.

In total, 118 sailors died aboard the Kursk , the most humiliating naval disaster for Russia since the Second World War. The eighty-six submariners not buried in St Petersburg rest in cemeteries scattered across Russia, mostly in hometowns where they grew up.

The headstones have the date of death marked as ‘12.08.2000’, the August day when twin explosions ripped through the submarine, killing most of those aboard within minutes. But the inscription for one of the sailors, Dmitri Kolesnikov, is the exception. There is no consensus, and considerable controversy, over when he died, so the date on the grave is written simply as ‘08.2000’ – with the exact day conspicuously absent.

The story of Captain-Lieutenant Kolesnikov, a twenty-seven-year-old Russian naval officer, is at the heart of this book, and of the new film Kursk , largely based on this account, starring Colin Firth and Matthias Schoenaerts.

Kolesnikov survived the initial explosions, saved by the thick steel walls protecting the submarine’s nuclear reactor. Trapped with twenty-two men, and as the most senior surviving officer, he organized a harrowing roll-call. In the flickering red half-light of the dying submarine, he made a list of those entombed in the aft compartment. The young officer later wrote a note to his wife and tucked it deep inside his survival suit in case he didn’t make it out alive.

Kolesnikov’s final written words, ‘Do not despair,’ are now engraved on the monument in the Serafmovskoye cemetery that pays tribute to the lost sailors.

On 12 thAugust 2000, as Dmitri Kolesnikov huddled in the rapidly deteriorating conditions of the submarine, along with the other sailors who had survived the shock-waves, resources were being mobilized around the world, pending Russian approval of an international rescue effort. The Royal Navy deployed its LR5 rescue submersible. British and Norwegian commercial deep sea divers raced to join the operation. The offers of assistance were in the finest maritime tradition of helping sailors in distress, irrespective of circumstances or nationality.

What happened next in the mission to save the Kursk survivors, and why, still leaves many of the rescuers who deployed into the Barents Sea baffled and angry. It leaves the families of the sailors heartbroken, forever asking the question of whether their loved ones might have been saved.

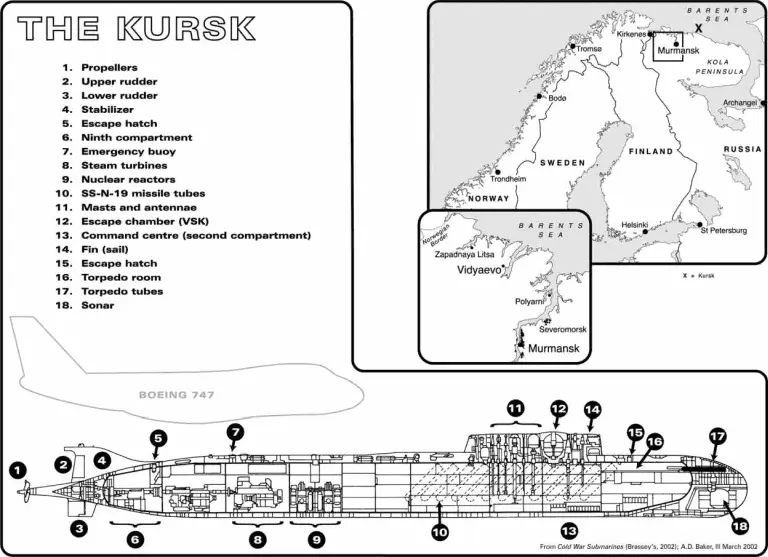

Tantalizingly, in some ways the Kursk was a dream set of circumstances for rescuers. The submarine hit the seabed in exceptionally shallow and clear water, settling upright at a depth of just a hundred metres, and at only a slight angle. On the surface, there were near-perfect sea conditions. There had been early detection of the emergency and rapid location of the accident site. Multiple naval bases along the Kola Peninsula were close by with many ‘vessels of opportunity’ that could act as the mother-ship for a Western rescue submersible. Even the international politics of the moment favoured success. The Cold War appeared to be over, and a freshly installed Russian President was keen to build stronger relationships with other nations, including former adversaries. The best way to boost cooperation was to accept the offers of help and supervise an unprecedented international mission to save Russian lives.

The safe evacuation of the twenty-three sailors gathered in the 9th Compartment would not have been straightforward. Submarine rescues are always technically challenging and frequently require improvisation and some good fortune, but the odds were certainly in favour of Kolesnikov and his comrades being saved. Once news broke of the accident just before noon on Monday, 14 August, reporters from around the world quickly made plans to travel to the Arctic port city of Murmansk. They had reasonable expectations of witnessing not just a dramatic and heart-warming rescue but a symbolic end to the risk-laden Cold War naval games that were still being silently played out by rival submarines beneath the ocean surface.

Only in retrospect – looking back now with nearly twenty years of knowledge of Russia’s trajectory – is it clear that the Kursk submarine disaster was about more than the fate of Russia’s most impressive nuclear-powered attack submarine. It was also a strikingly apt metaphor for that moment in the country’s history. Individual heroism, the defiant courage of families ashore, and the rebirth of Russian investigative journalism all collided head-on with the bureaucratic indifference and the authoritarian instincts of the state.

Throughout the 1990s, Russia was the scene of a titanic struggle for the soul of the country, as a battle was waged between reformers and oligarchs. The collapse of communism and the kleptocracy of the Yeltsin years had unleashed rapacious forces that were circling around Russia’s vast resources and natural wealth. Meanwhile, the country’s military apparatus was collapsing. Deprived of almost all funding from Moscow, far-flung bases had more in common with penal colonies than proud outposts of a superpower. This was particularly true in the secret submarine garrison towns along Russia’s rugged Arctic coastline. Harbours and inlets were contaminated with the rusting carcases of abandoned submarines. Wreckage and discarded equipment littered the shore. The infrastructure along the piers and aboard the barely operational ships rapidly deteriorated in the brutal winter months. The sailors’ salaries were rarely paid in full or on time. Training exercises and safety measures were a luxury the Navy could no longer afford. An accident was waiting to happen. The only question was aboard which ship, and on what scale.

Читать дальше