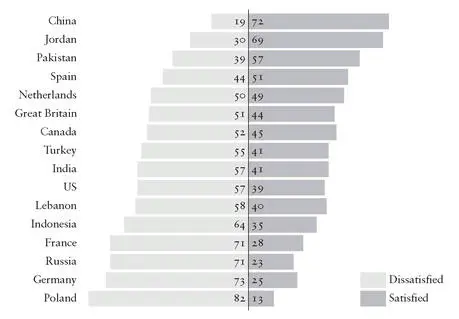

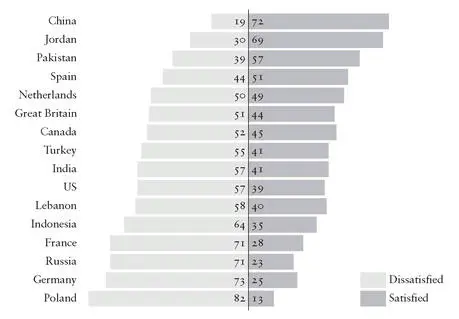

Figure 22. Percentage of population dissatisfied/satisfied with the condition of their country.

China ’s political reform has occurred gradually and incrementally. Unlike the economic reforms, the intention has never been to effect a systemic change, and certainly not to introduce Western-style democracy — rejected as incompatible with both China ’s traditions and present needs in the White Paper on Democracy published in 2005 [673] [673] www.china.org.cn/english/2005/Oct/145718.htm (accessed 15/6/08).

— but rather to modernize and codify political and administrative processes, thereby seeking to promote efficiency while maintaining political stability. The purpose of village elections, for example, has been good governance and functional efficiency rather than any move towards a wider process of democratization. [674] [674] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic? , pp. 126-7.

On the other hand, there has been a major expansion in civil liberties and human rights. Hong Kong opinion, which has traditionally been very sensitive to the lack of such rights in China, has become increasingly positive about trends to the north. In a 2008 survey in Hong Kong on the anniversary of the crack-down in Tiananmen Square, 85 per cent of respondents believed that human rights in China had improved since 1989, up from 78 per cent a year earlier. And the proportion who thought that they would improve further in the following three years rose to 77 per cent from 67 per cent a year earlier. Only 2 per cent thought that China ’s human rights record had worsened since 1989. [675] [675] ‘Tiananmen Recedes in Hong Kong ’, International Herald Tribune , 5 June 2008.

The boundaries of what it is now possible to say and do in China have expanded greatly, unless they concern the most sensitive subjects like Taiwan, Tibet, the Falun Gong religious sect, or the role of the Communist Party. This is most clearly apparent on the internet, which, although heavily policed in a manner that contradicts the utopian idea of the internet as a censorship-free zone, still allows a wide-ranging and frank discussion on all but the most delicate topics. [676] [676] Naomi Klein, ‘Police State 2.0’, Guardian, 3 June 2008.

There is also growing pressure for accountability with regard to the conduct of officials. In 2005 there were 87,000 ‘mass incidents’ (demonstrations, strikes, occupations, etc.) recorded by the Ministry of Public Security, many of which concerned the appropriation of land from farmers through sweetheart deals between developers and local government, from which officials benefited financially. Although these cases usually have little or nothing to do with the national authorities, the government has been seeking, in the face of gathering unrest, to strengthen farmers’ land rights in order to prevent such seizures. Details of a proposed new rural reform package that were divulged in October 2008 suggested that the rights of farmers would be strengthened by enabling them to trade in their thirty-year land-use contracts, a move which ought to have the effect of bolstering their security of tenure. [677] [677] Edward Wong, ‘A Bid to Help Poor Rural China Catch Up’, International Herald Tribune , 13 October, 2008; ‘On Solid Ground’, South China Morning Post , 23 February, 2008.

Similarly, in an attempt to improve labour conditions, the government introduced a new labour law in 2008 which enhanced the role of labour unions and made it harder for employers to fire workers or rely on casual labour; it was widely expected that the new laws would significantly improve workers’ wages and conditions. Meanwhile the government has predictably resisted the formation of independent labour associations.

The Maoist period involved the politicization of more or less the whole of society. The old Maoist slogan of ‘politics in command’ aptly summed up the nature of Communist rule until Mao’s death in 1976, with its constant calls for mass campaigns, symbolized most dramatically by the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, during the reform era there has been a steady process of depoliticization, accompanied by a steep decline in the importance of ideology. The highly politicized and obtrusive Maoist state has given way to what now looks more like a technocratic state, in the manner of other East Asian developmental states, [678] [678] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic? , p. 256.

although the powers of the Chinese state remain wide-ranging, from the one-child policy and internal migration to history books and the media. [679] [679] Howard W. French, ‘Letter from China ’, International Herald Tribune , 15 June 2006.

As the Party has shifted from ideological to instrumental rule, from a political to a technocratic approach, its relationship with the people has become less intrusive. There is, in effect, a new kind of social compact between the Party and the people: the task of the Party is to govern, while the people are left free to get on with the business of transforming their living standards. [680] [680] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic? , pp. 244-5.

Far from interesting themselves in politics, people have increasingly retreated into a private world of consumption. Money-making, meanwhile, has replaced politics as the most valued and respected form of social activity, including within the Party itself. The Party has actively encouraged its officials to enter business, not least as a means of galvanizing and mobilizing society. ‘Political loyalty’ has in some degree been replaced by ‘money’ as the measure of the political worth of Party cadres, resulting in a decline in the Party’s identity, a loss of its spiritual appeal and a process of internal decay. [681] [681] Ibid., pp. 245-6.

The Party has increasingly sought to transform itself from a revolutionary organization into a ruling administrative party. [682] [682] Howell, Governance in China , p. 30; Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic ? p. 159.

It prioritizes technical competence, entrepreneurship and knowledge over, as previously, revolutionary credentials, military record and class background, with a technocratic class rather than revolutionaries now in charge of the Party. [683] [683] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic? , p. 229.

There have been drastic changes in the social composition of the Party leadership over the last twenty years. Between 1982 and 1997 the proportion of the central committee who were college-educated rose from 55.4 per cent to 92.4 per cent. By 1997 all seven members of the standing committee of the central committee’s political bureau (the top leadership) were college-educated in technical subjects like engineering, geology and physics, while eighteen of the twenty-four political bureau members were also college-educated. [684] [684] Ibid., pp. 256-60.

The Party has opened its doors to the new private capitalists in an effort to widen its representativeness and embrace the burgeoning private sector. By 2000 20 per cent of all private entrepreneurs were members of the Party. [685] [685] Ibid., p. 269.

This is not surprising given that by 1995 nearly half of all private capitalists had previously been Party and government officials. [686] [686] Ibid., p. 266.

The large-scale shift of Party and government officials into the private sector has almost certainly been the biggest single reason for the enormous increase in corruption, as some of them exploited their knowledge and connections to appropriate state property, gain access to cash reserves, and line their own pockets. The problem poses a grave challenge to the Party because, if unchecked, it threatens to undermine its moral standing and legitimacy. Despite a series of major, high-profile campaigns against corruption, of which the most prominent casualty so far has been the former Communist Party chief in Shanghai, Chen Liangyu, the evidence suggests that the problem remains huge and elusive because its roots lie deep within the Party itself and the myriad of guanxi connections. [687] [687] Ibid., pp. 93, 265-6. The examples are legion: ‘China Oil Tycoon Placed Under Arrest’, South China Morning Post , 27 December 2006; ‘ China Fund Says Almost $1 billion Misused’, International Herald Tribune , 25-6 November 2006; and ‘Shenzhen Tycoon on Trial for Theft’, South China Morning Post , 13 November 2006.

Читать дальше