Zheng took to the places he visited [in Africa] tea, chinaware, silk and technology. He did not occupy an inch of foreign land, nor did he take a single slave. What he brought to the outside world was peace and civilization. This fully reflects the good faith of the ancient Chinese people in strengthening exchanges with relevant countries and their people. This peace-loving culture has taken deep root in the minds and hearts of Chinese people of all generations. [1239] [1239] Quoted in Chris Alden, China in Africa (London: Zed Books, 2007), p. 19.

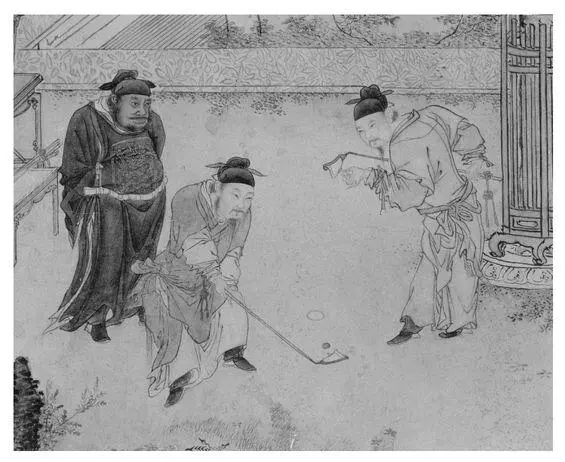

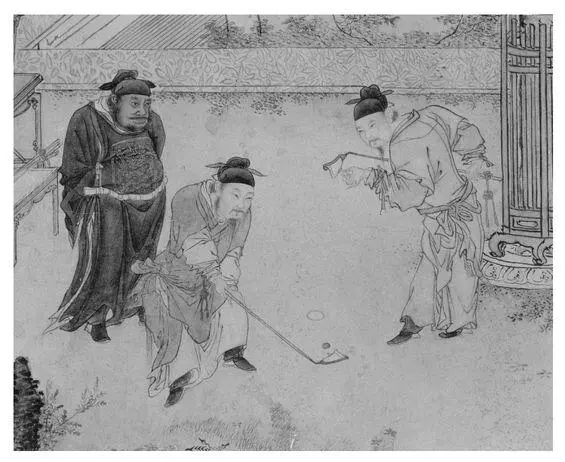

On a light-hearted note, there is evidence to suggest that the game of golf originated in China. A Ming scroll entitled The Autumn Banquet , dating back to 1368, shows a member of the imperial court swinging what resembles a golf club at a small ball, with the aim of sinking it in a round hole. In Chinese the game was known as chuiwan , or ‘hit ball’. [1240] [1240] Patrick L. Smith, ‘Museum’s Display Links the Birth of Golf to China ’, International Herald Tribune , 1 March 2006.

It is reasonable to surmise that many of the sports that have previously been regarded as European inventions, and especially British, actually had their origins in other parts of the world: the British, after all, had plenty of opportunity to borrow and assimilate games from their far-flung empire and then codify the rules. As we move beyond a Western-dominated world, these kinds of discoveries and assertions will become more common, with some, perhaps many, destined to gain widespread acceptance.

BEIJING AS THE NEW GLOBAL CAPITAL

At the turn of the century, New York was the de facto capital of the world. Nothing more clearly illustrated this than the global reaction to 9/11. If the same fate had befallen the far more splendid Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, the disaster would have been fortunate to have commanded global headlines for twelve hours, let alone months on end. New York ’s prominence owes everything to the fact that it is the financial capital of the world, the home of Wall Street, as well as a great melting pot and the original centre of European immigration. New York ’s global status is, however, largely a post-1945 phenomenon. In 1900, during the first wave of globalization, the world’s capital was London. And in 1500, arguably Florence was the most important city in the world (though in that era it could hardly have been described as the global capital). In 1000 perhaps Kaifeng in China enjoyed a similar status, albeit unknown to most of the world, while in AD 1 it was probably Rome. [1241] [1241] Nicholas D. Kristof, ‘Glory is as Ephemeral as Smoke and Clouds’, International Herald Tribune , 23 May 2005.

Looking forward once again, it seems quite likely that in fifty years’ time — and certainly by the end of this century — Beijing will have assumed the status of de facto global capital. It will face competition from other Chinese cities like Shanghai, but as China ’s capital, the centre of the Middle Kingdom and the home of the Forbidden City, Beijing ’s candidature will be assured, assuming China becomes the world’s leading power.

But this is not simply a matter of Beijing ’s status. We can assume that Chinese hegemony will involve at least four fundamental geopolitical shifts: first, that Beijing will emerge as the global capital; second, that China will become the world’s leading power; third, that East Asia will become the world’s most important region; and fourth, that Asia will assume the role of the world’s most important continent, a process that will also be enhanced by the rise of India. These multiple changes will, figuratively at least, amount to a shift in the earth’s axis. The world has become accustomed to looking west, towards Europe and more recently the United States: that era is now coming to an end. London might still represent zero when it comes to time zones, a legacy of its once-dominant status in the world, [1242] [1242] Dava Sobel, Longitude (London: Fourth Estate, 1998).

but the global community will increasingly set its watches to Beijing time.

THE RISE OF THE CIVILIZATION-STATE

The world has become accustomed to thinking in terms of the nation-state. It is one of the great legacies of the era of European domination. Nations that are not yet nation-states aspire to become one. The nation-state enjoys universal acceptance as the primary unit and agency of the international system. Since the 1911 Revolution, even China has sought to define itself as a nation-state. But, as we have seen, China is only latterly, and still only partially, a nation-state: for the most part, it is something very different, a civilization-state. As Lucian Pye argued:

China is not just another nation-state in the family of nations. China is a civilization pretending to be a state. The story of modern China could be described as the effort by both Chinese and foreigners to squeeze a civilization into the arbitrary and constraining framework of a modern state, an institutional invention that came out of the fragmentation of Western civilization. [1243] [1243] Lucian W. Pye, The Spirit of Chinese Politics (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 235.

It is this civilizational dimension which gives China its special and unique character. Most of China ’s main characteristics pre-date its attempts to become a nation-state and are a product of its existence as a civilization-state: the overriding importance of unity, the power and role of the state, its centripetal quality, the notion of Greater China, the Middle Kingdom mentality, the idea of race, the family and familial discourse, even traditional Chinese medicine.

Hitherto, the political traffic has all been in one direction, the desire of Chinese and Westerners alike to conform to the established Western template of the international system, namely the nation-state. This idea has played a fundamental role in China ’s attempts to modernize over the last 150 years from a beleaguered position of backwardness. But what happens when China no longer feels that its relationship with the West should be unidirectional, when it begins to believe in itself and its history and culture with a new sense of confidence, not as some great treasure trove, but as of direct and operational relevance to the present? That process is well under way [1244] [1244] Suisheng Zhao, A Nation-State by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), pp. 147-9.

and can only get stronger with time. This will inexorably lead to a shift in the terms of China ’s relationship with the international system: in effect, China will increasingly think of itself, and be treated by others, as a civilization-state as well as a nation-state. As we saw in Chapter 9, this has already begun to happen in East Asia and in due course it is likely to have wider global ramifications. Instead of the world thinking exclusively in terms of nation-states, as has been the case since the end of colonialism, the lexicon of international relations will become more diverse, demanding room be made for competing concepts, different histories and varying sizes.

THE RETURN OF THE TRIBUTARY SYSTEM

The Westphalian system has dominated international relations ever since the emergence of the modern European nation-state. It has become the universal conceptual language of the international system. As we have seen, however, the Westphalian system has itself metamorphosed over time and enjoyed several different iterations. Even so, it remains what it was, an essentially European-derived concept designed to make the world conform to its imperatives and modalities. As a consequence, different parts of the world approximate in differing degrees to the Westphalian norm. Arguably this congruence has been least true in East Asia, where the legacy of the tributary state system, and the presence of China, mean that the Westphalian system exists in combination with, and on top of, pre-existing structures and attitudes. The specificity of the East Asian reality is illustrated by the fact that most Western predictions about the likely path of interstate relations in the region since the end of the Cold War and the rise of China have not been borne out: namely, that there would be growing instability, tension and even war and that the rise of China would persuade other nations to balance and hedge against it. In the event, neither has happened. There have been fewer wars since 1989 than was the case during the Cold War, and there is little evidence of countries seeking to balance against China: on the contrary, most countries would appear to be attempting to move closer to China. [1245] [1245] David C. Kang, ‘Getting Asia Wrong: The Need for New Analytical Frameworks’, International Security , 27: 4 (Spring 2003), pp. 57, 61-5.

This suggests that the modus operandi of East Asia is rather different to elsewhere and contrasts with Western expectations formed on the basis of its own history and experience. A fundamental feature of the tributary state system was the enormous inequality between China and all other nations in its orbit, and this inequality was intrinsic to the stability that characterized the system for so long. It may well be that the new East Asian order, now being configured around an increasingly dominant China, will prove similarly stable: in other words, as with the tributary system, overweening inequality breeds underlying stability, which is the opposite to the European experience, where roughly equal nation-states were almost constantly at war with each other over many centuries until 1945, when, emerging exhausted from the war, they discovered the world was no longer Eurocentric. [1246] [1246] Ibid., pp. 66-8, 79–82.

Читать дальше