The present international system is designed primarily to represent and promote American interests. As China’s power grows, together with that of other outsiders like India, the United States will be obliged to adapt the system and its institutions to accommodate their demands and aspirations, but, as demonstrated by the slowness of reform in the IMF and even the G8, there is great reluctance on the part of both the US and Europe. [1218] [1218] Bob Davis, ‘IMF Gives Poor Countries Scarce New Voting Count’, Wall Street Journal , 31 March 2008; Mark Weisbrot, ‘The IMF’s Dwindling Fortunes’, Los Angeles Times , 27 April 2008; Jeffrey Sachs, ‘How the Fund Can Regain Global Legitimacy’, Financial Times , 19 April 2006; George Monbiot, ‘Don’t Be Fooled By This Reform: The IMF Is Still the Rich Man’s Viceroy’, Guardian , 5 September 2006; Joseph Stiglitz, ‘Thanks for Nothing’, Atlantic Monthly , October 2001.

Fundamental to this has been the desire to retain these institutions for the promotion of Western interests and values. For example, after China and Russia vetoed the Anglo-American bid to impose sanctions on the Zimbabwe president Robert Mugabe and some of his regime in July 2008, the US ambassador to the UN, Zalmay Khalilzad, stated that Russia’s veto raised ‘questions about its reliability as a G8 partner’. [1219] [1219] ‘Fury as Zimbabwe Sanctions Vetoed’, 12 July 2008, posted on www.bbc. co.uk/news.

From late 2008 there was much talk of a new Bretton Woods, but any such agreement would require far more fundamental reform than the West has hitherto entertained. At present the Bretton Woods institutions — the IMF and the World Bank — are dominated by the Western powers. The US still has 17.1 per cent of the quotas (which largely determine the votes) and the European Union an additional 32.4 per cent in the IMF as of May 2007, while China had just 3.7 per cent and India 1.9 per cent. [1220] [1220] Martin Wolf, ‘Why Agreeing a New Bretton Woods is Vital’, Financial Times , 4 November 2008.

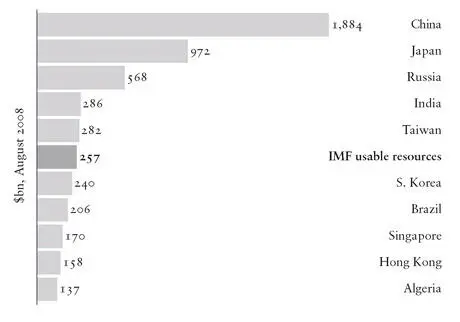

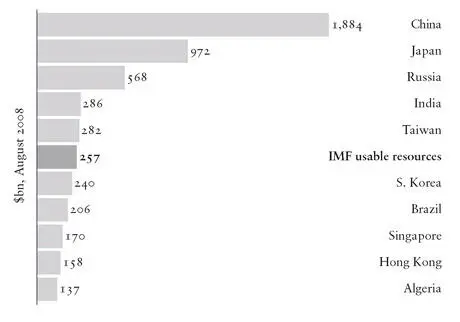

If these institutions are to be revived as a result of any new agreement, the West will have to cede a large slice of its power to countries like China and India. China, after all, is hardly likely to put very large resources at the disposal of the IMF unless it has a major say in how they are used, as Premier Wen Jiabao has made clear. [1221] [1221] ‘Interview: Message from Wen’, Financial Times , 1 February 2009.

Should reform remain reluctant, partial and ultimately inadequate, then the international system is likely over time to become increasingly bifurcated, with the Western-sponsored bodies abandoning any claim to universality in favour of the pursuit of sectional interest, while a new Chinese-supported system begins to take shape alongside. [1222] [1222] For a pessimistic view of the prospects for a new Bretton Woods agreement, see Gideon Rachman, ‘The Brettons Woods Sequel Will Flop’, Financial Times , 10 November 2008.

Figure 40. IMF resources and countries with largest foreign exchange reserves.

The American international relations scholar G. John Ikenberry has argued that because the ‘Western-centred system… is open, integrated, and rule-based, with wide and deep foundations’, ‘it is hard to overturn and easy to join’: [1223] [1223] G. John Ikenberry, ‘The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?’, Foreign Affairs , January/February 2008, p. 1 (available at www.foreignaffairs.org).

in other words, it is far more resilient and adaptable than previous systems and therefore is likely to be reformed from within rather than replaced. This is possible, but perhaps more likely is a twin-track process: first, the gradual but reluctant and inadequate reform of existing Western-centric institutions in the face of the challenge from China and others; and second, in the longer term, the creation of new institutions sponsored and supported by China but also embracing other rising countries such as India and Brazil. As an illustration of reform from within, in June 2008 Justin Lin Yifu became the first Chinese chief economist at the World Bank, a position which previously had been the exclusive preserve of Americans and Europeans. [1224] [1224] Martin Jacques, ‘The Citadels of the Global Economy are Yielding to China ’s Battering Ram’, Guardian , 23 April 2008.

In the long term, though, China is likely to operate both within and outside the existing international system, seeking to transform that system while at the same time, in effect, sponsoring a new China-centric international system which will exist alongside the present system and probably slowly begin to usurp it. The United States will bitterly resist the decline of an international system from which it benefits so much: as a consequence, any transition will inevitably be tense and conflictual. [1225] [1225] Yu Yongding, ‘The Evolving Exchange Rate Regimes in East Asia ’, unpublished paper, 12 March 2005, p. 9.

Just as during the interwar period British hegemony gave way to competing sterling, dollar and franc areas, American hegemony may also be replaced, in the first instance, at least, by competing regional spheres of influence. It is possible to imagine, as the balance of power begins to shift decisively in China ’s favour, a potential division of the world into American and Chinese spheres of influence, with East Asia and Africa, for example, coming under Chinese tutelage, and forming part of a renminbi area, while Europe and the Middle East remain under the American umbrella. In the longer run, though, such arrangements are unlikely to be stable in a world which has become so integrated. [1226] [1226] Interview with Shi Yinhong, 19 May 2006.

11. When China Rules the World

I want to ponder what the world might be like in twenty, or even fifty, years’ time. The future, of course, is unknowable but in this chapter I will try to tease out what it might look like. Such an approach is naturally speculative, resting on assumptions that might prove to be wrong. Most fundamentally of all, I am assuming that China ’s rise is not derailed. China ’s economic growth will certainly decline within the time-frame of two decades, perhaps one, let alone a much longer period. It is also likely that within any of the longer time-frames there will be profound political changes in China, perhaps involving either the end of Communist rule or a major metamorphosis in its character. None of these eventualities, however, would necessarily undermine the argument that underpins this chapter, that China, with continuing economic growth (albeit at a reduced rate), is destined to become one of the two major global powers and ultimately the major global power. What would demolish it is if, for some reason, China implodes in a twenty-first-century version of the intermittent bouts of introspection and instability that have punctuated Chinese history. This does not seem likely, but, given that China ’s unity has been under siege for over half of its 2,000-year life, this eventuality certainly cannot be excluded.

The scenario on which this chapter rests, then, is that China continues to grow stronger and ultimately emerges over the next half-century, or rather less in many respects, as the world’s leading power. There is already a widespread global expectation that this may well happen. As can be seen from Table 6, a majority of Indians, for example, believe that China will replace the United States as the dominant power within the next twenty years, while almost as many Americans and Russians believe in this scenario as think the contrary.

Читать дальше