Eugenia Maresch

KATYN 1940

The Documentary Evidence of the West’s Betrayal

If it be the case that a monstrous crime has been committed by a foreign government – albeit a friendly one – and that we, for however valid reasons, have been obliged to behave as if the deed was not theirs, may it not be that we now stand in danger of bemusing not only others but ourselves? … We ought, maybe, to ask ourselves how, consistent with the necessities of our relations with the Soviet Government, the voice of our political conscience is to be kept up to concert pitch. It may be that the answer lies, for the moment, only in something to be done inside our own hearts and minds where we are masters. Here at any rate we can make a compensatory contribution – a reaffirmation of our allegiance to truth and justice and compassion.

Owen O’Malley

To my life-long friend and mentor, prelate Lt Zdzisław Peszkowski, survivor of Kozielsk camp, who in 1944 became a Scout leader to thousands of Polish refugee children – myself included – and to Dr Zdzisław Jagodziński, historian, librarian and first editor of the Katyn bibliography, my courageous friend and colleague; both now departed, without ever seeing the fruits of their inspiration.

Front cover: Big Ben, Wartime London. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library ARC 195565)

Grateful acknowledgements are made to various archives for permission to reprint previously published material as well as those documents recently declassified, upon which the bulk of this book is based. In particular the National Archives at Kew, the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, custodian of surviving records of the Polish government-in-exile based in London. Besides referring to the relevant official histories I have also drawn freely on recent publications by authors from Poland and these are acknowledged in the endnotes.

Debts of gratitude are owed to the personnel of the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, and the Polish Underground Movement Study Trust, the National Archives in Poland, the Central Military Archives and the Council for Defence of Memory, Strife and Martyrdom in Warsaw, for their support and encouragement.

Thanks are due to my family, friends and colleagues, amongst them Andrzej Suchcitz, whose counsel I have sought on many occasions, and to David List, especially for his meticulous eye for detail, whose critical reading of the typescript resulted in rational re-examination.

Appreciation is expressed to those who allowed me to use photographs from their family albums. All credits are noted in the captions to those libraries and institutions that provided images.

CHAPTER ONE

DRANG NACH OSTEN AND PRISONERS OF WAR

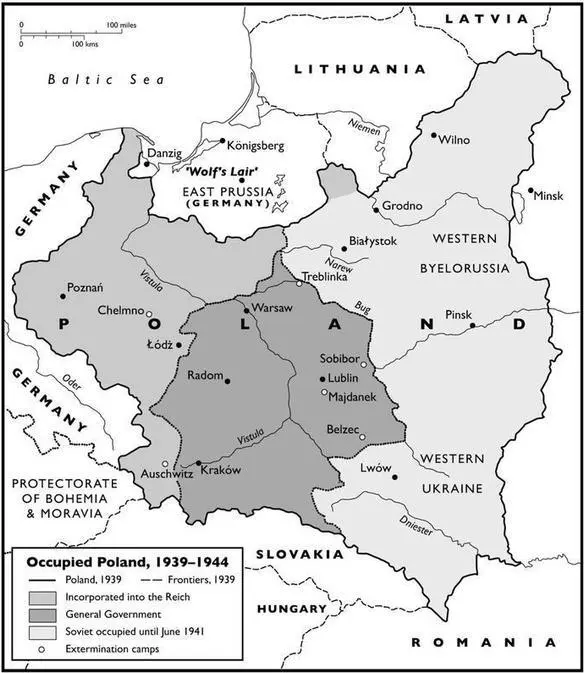

Seventy years ago, Hitler’s quest for domination of Eastern Europe continued with a blistering attack on Poland on 1 September 1939. Seventeen days later, Stalin ‘plunged the knife in Poland’s back’, as agreed by both tyrants on 23 August 1939. The German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov signed the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, which contained a Secret Supplementary Protocol dealing with territorial allocations. Initially, boundaries had been along the rivers Narew, Wisła and San, but after the formal German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Borders, signed in September, they settled on the Pisa, Narew, Bug and San. The new boundary stretched roughly east of Białystok, through Brześć Litewski (Brest Litovsk) to the west of Lwów (Lviv, Lvov), a south-eastern Polish fortress, which for centuries had withstood the invasion of Turkish and Tartar hordes. The Soviet strategy was to create two fronts: the Belorussian heading from Smolensk and the Ukrainian from Kiev, enabling a swift destruction of the Polish regular army divisions and some 24 Frontier Defence Corps ( KOP, Korpus Obrony Pogranicza ) stationed on the Polish borders. Under the guise of ‘rescuers’ of the Ukrainian and Belorussian minorities, the Red Army overran the eastern territories of Poland, always known as Kresy, inhabited by 12 million people – in just twelve days.

On 18 September 1939 the two aggressors met to discuss further political cooperation; a communiqué was signed, declaring that the sovereignty of Poland had been ‘disestablished’. The demarcation line was confirmed and the new territorial sphere of influence endorsed. As early as 19 September 1939, Lavrenty Beria, [1] Lavrenty Beria (1899–1953) in 1939 Commissar General of the Internal Security NKVD ( Narodny Komissariat Vnutennikh Diel ) of the USSR, member of the Politburo and a close friend of Stalin. He was instrumental in submission of a resolution on 5 March 1940 to shoot the Polish PoWs. After Stalins’ death Beria was charged with ‘anti state’ crimes and was executed on 23 December 1953.

People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, head of the Secret Police the NKVD ( Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del ) by order No.0308, had created a separate directorate of the UPV ( Upravlenie po Delam Voennoplennykh) – an authority to administer wartime operations of the NKVD, primarily to deal with prisoners of war (PoW) headed by Major Pyotr Soprunenko. [2] Pyotr Karpovich Soprunenko (1908-1992) Soviet Security official NKVD, close to Beria, head of PoW administration (1939-1944). Supervised ‘clearing out’ of the three camps. In 1990, identified as a witness to the massacre.

On 2 December 1939, Beria produced another official note for Stalin’s [3] Joseph Stalin (Iosif Vassarionovich Dzhugashvili) (1879-1953). Born in Georgia, member of Lenin’s Bolshevik Party (1903–1917), party bureaucrat and Soviet leader (1928-1953). Introduced wholesale purges and crimes against his own people, created the GULags; responsible for the massacres of the Polish PoWs. Considered by the Russians as a man of steel, who led them to victory and domination over Eastern Europe; denounced by his accomplice Khrushchev in 1956 and by the last president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1990.

approval, which was endorsed by the Politburo of the Communist Central Committee on 4 December – to organize four mass deportations of Polish civilians to the wilderness of Siberia and other Soviet Republics. In 1940–1941, according to émigré sources, at least 980,000 were deported; incomplete statistics, gathered to date from GULag’s NKVD documents, show only 316,000. These were combatants of the 1920 war with their families, landowners, police and civil servants, ‘enemies of communism and counter-revolutionaries’, destined for hard labour and death.

December was also a month of intensive consultations between Germany and Russia on the subject of the massive prisoner problem. Three joint meetings of the security services the UPV and the Gestapo for RSHA, the Reich Central Security Office ( Reichsicherheitshauptamt ), were held to discuss the possibility of territorial exchange of the PoWs as well as relocation of forced labour to GULags in the USSR and concentration camps in Germany. It is possible that the fate of some 15,000 Poles detained in Soviet camps and over 7,000 kept in prisons was decided at one of these three meetings, Lwów in October 1939, Kraków in January 1940 and Zakopane in March 1940. It is as yet unknown, due to lack of documentation, if this treachery is analogous to, or part of, the German ‘pacification action’, the Aktion AB ( Ausserordentliche Befriedungsaktion ), designed not only to stop any resistance by the people but also to exterminate Polish leaders and the elite, which was planned by the Generalgouvernment in early 1940 and reached its height from May to July. Aktion AB was sanctioned by Adolf Hitler and carried out by Generalgouverneur Hans Frank, Governor General of the occupied part of Poland, with its seat in Kraków and acting SS-Obergruppenfuhrer, head of the Nazi Security Service in Poland, ably assisted by Friedrich W. Kruger and others.

Читать дальше