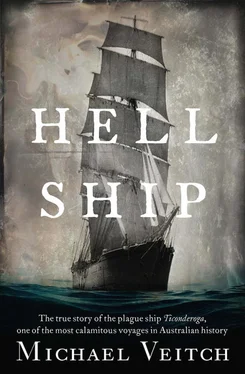

And so they did wait, the rest of that day, then all night, then all the following day and then yet another night. This had not been planned for. The ship’s bunks and bedding were long gone, and there was virtually nowhere to sleep. The galleys had not been prepared for use and food was limited to what remained of the old store of ship’s biscuits. To many, the Ticonderoga once again began to feel like the prison of old.

Finally, on Christmas Eve, after some deft negotiating by Captain Boyle, a solution of sorts began to take shape. The weather was hot and windy, with an ominous bank of thick grey cloud building up in the western sky. With this dramatic backdrop, Boyle announced that a solution had been found. What he did not know was that it involved one of the most unfortunate vessels in the colony, the paddle-steamer Maitland.

She was old, a smallish vessel of just over 100 tons, built as a transport to run coal between Newcastle and Sydney. In 1851, the Maitland was bought as an investment by the colourful entrepreneur Captain George Ward ‘Old King’ Cole, who must immediately have regretted the decision. Cole had made a fortune around the colonies in such dubious trades as sandalwood and opium, had built the city’s first private wharf on his property on the Yarra River, as well as the first screw steamer in the southern hemisphere, and was one of the young town’s social celebrities. He counted Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe among his wealthy and influential friends, and was famous for his lavish outdoor parties, attended by hundreds of the well-to-do, with no expense spared. He had had recent success running passenger services across Bass Strait to Tasmania, but saw an opening in the market for providing a similar service between Melbourne and Geelong. Besides, he needed a cash flow to compensate for the recent decision of the government to close his private wharf due to the phenomenon of absconding ships’ crews. Deciding to buy and refit the old Maitland as a passenger vessel, he put her under the command of one Robert Dyson. When nearly ready to begin operating, however, Dyson almost drowned in his cabin when, for no apparent reason, the Maitland started to sink around him while tied up at Queen’s Wharf.

The reason for her sinking was never discovered, but Cole decided to fork out for the old tub to be re-floated and repaired nonetheless. But the Maitland ’s ill luck continued, however, when in October 1852, the hapless Captain Dyson was at fault in a collision with another vessel, which he damaged severely, and which just happened to be the official boat of Governor La Trobe’s Chief Health Officer, Dr Thomas Hunt—who, as we have seen in his dealings with Dr Taylor, was not a man to suffer fools or incompetence lightly.

Following the accident, a furious Hunt was forced to borrow a Customs boat to carry out his work, and promptly laid a charge against Captain Dyson and Cole, her owner, who he disliked in any case, eminent social status notwithstanding. Sensing that there was no future in the Maitland as a passenger ship, Cole decided to use her simply as a tug. Few people, however, wanted to use her, and Cole started to realise he had been saddled with a lemon. Thus when the big black clipper said to be a plague ship arrived and dropped anchor in the bay, only to be summarily ignored by all, Dyson saw an opportunity for the Maitland to at last turn a profit.

Being the only vessel to have approached her, Dyson and Boyle needed only a brief conversation. Yes, Dyson would take his passengers off and deposit them up the Yarra River at Queen’s Wharf, but he would charge them handsomely for the privilege. For the passengers, there was no choice in the matter. Boyle, however, insisted that it would be done in an orderly fashion, with people being required to stay below decks until they were called up to embark on the Maitland .

As the preparations were beginning for the first of the passengers, the thunderstorm that had been threatening all morning broke suddenly and violently over the bay and a squall sprang up, rocking the ship dramatically. Then, at its height, a bolt of lightning struck one of the yardarms, setting it on fire. The accompanying thunderclap was startling enough for the people below, but with the accompanying shouts of ‘Fire!’ heard from above, pandemonium broke out below. Believing the Ticonderoga to be ablaze, passengers made a rush for the hatches, but Boyle quickly ordered them battened down to avoid a deadly panic. The flames were quickly extinguished by the crew, and Boyle managed to convince his people that they were in not, in fact, in danger, but he could see that all of them were frazzled and at the end of their wits.

The first group of passengers resumed their embarkation onto the Maitland without further incident—not that the welcome from Captain Dyson was a warm one. Neither he nor his small crew would come anywhere near these ragged people, fearing they would be instantly struck down with whatever ghastly disease they happened to have. He angrily barked at them to load on, at one stage not even waiting for a husband to gather his wife and seven-week-old infant, who were left on the ship until the next run. [1] Kruithof, 2002, p. 86

After what they had been through, for the passengers of the Ticonderoga , this was the final ignominy .

Back and forth the Maitland putted all day of that Christmas Eve, making the 12-kilometre run from the ship to Queen’s Wharf on the Yarra River, observed by a growing crowd of onlookers. When word got around that they were from the dreaded plague ship stranded out in the bay , some quietly shuffled away, while still others gathered to gape. It was a world away from how the passengers had once envisaged their entry into Melbourne, but at least they had arrived, and could finally begin to think about the next stage of their journey and their lives.

One of the onlookers that day, despite the reputation accompanying the ship and her passengers, allowed his curiosity to prevail, and approached Captain Dyson as he was preparing to return to the ship for another load. He would like to go out and see this so-called plague ship for himself, he said, and requested a passage. Dyson looked at the man as if he were deranged, but was happy enough to accept his money. Out in the bay, not content with simply viewing the Ticonderoga from the deck of the Maitland , the curious passenger even went aboard her for a half-hour inspection while another load of people was being prepared.

Two days later, on 31 December 1852, one of the most controversial missives of the entire saga appeared in the letters to the editor pages of The Argus . Signing himself simply ‘Observer’ , the anonymous gentleman penned the following:

Sir—On Friday last I had occasion to visit the Bay on business, and while going round the shipping in the Maitland, we called alongside of the Ticonderago [ sic ], for the purpose of bringing the passengers up to town. Being a sea-faring man and curious to know the state of the vessel which had been the scene of such unparalleled disease I went on board, and very soon ceased to be surprised at anything which had taken place on board this ill-fated vessel. The miserable squalid appearance of the passengers at once attracted my attention, and on looking down the hatchway, the smell and appearance of the between decks was so disgusting, that though accustomed to see and be on board of slave vessels, I instinctively shrank from it. I have no hesitation in expressing it as my decided opinion that the disease in this ship was mainly caused by the carelessness and inattention to cleanliness on the part of the master and his officers, and the want of ventilation. Several people were lying about the decks, apparently in the last stage of disease, and the passengers were bundled over the side without any accommodation ladder or the least regard to decency and decorum. In fact, the captain and crew seemed to look upon them as perfect nuisances, to be got rid of on any terms. The invalid women were carried over the side on men’s backs, and one poor creature was separated from his child of seven weeks old, another child of 5 years of age died on board the steamer before we reached the wharf, no arrangements were made at the wharf for the reception of the sick, and two women in a dying state, were taken away in common wharf drays.

Читать дальше