As far as I was concerned, that’s where the matter ended. But when I got off the cable car the next time, the adjutant was waiting for me. ‘The Colonel is very grateful,’ he said in passable English. ‘He invites you to lunch at the Post Hotel at 13.00 hours please.’ Who was I to decline such hospitality? Furthermore, the weather was closing-in, skiing wouldn’t be good, anyway. I changed into uniform and made my way to the Post Hotel, one of Europe’s famous resort hotels, situated in the centre of things and full of style and atmosphere. The owners, the Clausing family, had, I hoped, been taken to less elegant quarters, probably jail or internment, because of their devoted services rendered to the beloved Fuehrer. Many of the staff remained however and were now serving the officers of the US Army, whose club the Post had become. I was assigned accommodation there on a later occasion and found myself occupying the owner’s suite. Somehow, none of my American predecessors had applied the fine-tooth-comb treatment to the rooms and I discovered a hidden cupboard which I pried open. It contained such sought-after articles as SS ‘Daggers of Honour’ with the Clausing initials and several rather nice pistols and revolvers, which I felt compelled to impound.

I drank to excess on those occasions and am reminded of a drinking contest I organised between some fine, upstanding men. A friendly argument had arisen, in the library of the courthouse, between an American major, Sam Harris, Major Airey Neave of the British Army, a French colonel and a Russian major, over the question of who among those present in Nuremberg, was best able to hold their liquor – the French, the Russians, the British, or the Americans.

Anxious to ingratiate myself with my higher-ups, I ventured the innocent suggestion that the answer could be found later in the evening, at the Grand Hotel. Part of my thinking was based on patriotism. I had been out drinking with Airey Neave for one whole night earlier and at 07.30 hours the following morning he was standing up, admirably straight and seemingly sober in spite of the vast amounts of whisky we had absorbed. Such a man, I knew, would keep our flag flying. I was appointed referee and ordered not to drink, which was an undesirable development I had not foreseen. It goes without saying that at 21.00 hours that night, the Russian side appeared, armed with Vodka, France brought Cognac, Sam Harris was toting some bottles of Southern Comfort and Airey Neave was accompanied by man’s best friend, John Haig, Black Label. Simple rules were to apply. I would fill the glasses with the chosen liquid, refill them when all four were empty, and he who stood up at the end would be declared the winner. The first white flag was raised by France.

Major Sam Harris, United States Army, retired next, to an arm-chair in the rear of the arena, where he fell into the sleep of the innocent. That left the Soviet Socialist Republic and the British Empire to settle the issue. We were in the early morning hours by now, and my seniors were finishing their second bottles. Then the Russian rose. He did not, as might be expected, lurch to his feet. He stood up straight ‘Mister Neave,’ he said, ‘I will not go on. You win.’ And he clinked glasses with Airey, sank back in his chair and passed out. Major Neave, the victor, cast a loving glance at the Black Label before him, sat down in the nearest chair and he too fell asleep.

At about that time I received the news that I was to be discharged from the British Army and my orders stated that I should report to an Army depot at Guildford to be removed from His Majesty’s payroll. The depot at Guildford was enormous; soldiers poured in at one end and somewhat odd-looking civilians in dreadful demob suits emerged from the other.

The paperwork came first, ending with the handing over of the wartime gratuity, a cash payment of, in my case, £166 in addition to one month’s staff captain’s pay. After five and-a-half-years of serving the cause of freedom faithfully I was now free myself – and rich.

I did a little stock taking. Did I regret the loss of those years? No, I didn’t want to stay out of the war, I went through it, not as I had planned, but by doing the next best thing. Interment was a matter to be forgotten, though not forgiven. Did I enjoy some of it? Yes, the comradeship, the rivalry, the supreme physical fitness, the corners cut, the battles of wits – some of them won. Did I hate some of it? Yes. The time wasted in the Pioneers, the despicable types chosen as our superiors – the frustration, in other words. Did I profit from it all? And how! Self-discipline, tenacity, patience, self-control had been acquired and would remain constant assets. Was I a success? Emphatically no, as a soldier, but yes, in making a case for myself, and many more like me. I was now thirty-three years old, halfway, let’s say, along the road of life. The order of the day was, clearly, to ‘keep it up’ for at least as long I am winning.

We are told that the unhappy frame of mind of a new soldier is called ‘joining shock.’ Nobody has ever mentioned ‘demob shock’ but it certainly exists – only it is over much more rapidly – to be replaced by utter euphoria!

On the morning after my metamorphosis I went to see my tailors in Maddox Street. They had not seen me since delivering a set of tails to me in September 1939, worn only once during an ill-feted theatrical appearance. I was greeted as if I had not been away. I was wearing my uniform, now an illegal thing to do, in order to save them the shock of seeing me in my gratuitous demob outfit. I ordered four suits, one to be delivered forthwith, the others to be sent to Nuremberg. As I was departing the elderly gentleman who always looked after me, took me aside. ‘Would you mind, Sir,’ he whispered, ‘taking care of your last account, I mean the bill for the three suits we delivered to you in August and September 1939 – if it wouldn’t inconvenience you too much, Sir.’ They had never once sent me a reminder and I had completely forgotten that the account was unpaid. Those days have gone. But I am glad to say that I still have, and am still wearing, the suits.

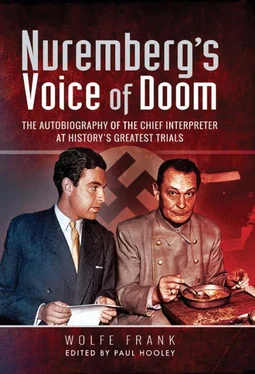

32. WOLFE FRANK OF THE F.O.

PROUDLY WEARING MY NEW SUIT, I returned to Nuremberg under the auspices, of all things, the British Foreign Office; Dostert had demanded that I return after coming out of the Army and things had been arranged accordingly. I was no longer subject to Army discipline and regretted that this had not occurred before my friend Hugh Turrell had left – we could have had such a happy, frank exchange of views.

My pay, now called salary, was better, of course, and I was assigned back to my quarters at the Grand Hotel. I still had the Opel and was entitled to use all the US facilities available to Allied personnel involved in the trial.

My twenty-one ‘clients’ in the dock looked up with interest when I appeared in a new suit. There were even some barely concealed grins. Schacht, who sat nearest to the English booth, slowly nodded approval.

I went into the booth to interpret the testimony of Albert Speer, the man who has emerged as being the most remarkable of the top Nazis on trial; by virtue of the books he published after serving his twenty-year prison sentence and his rather dignified re-entry into human society.

As Hitler’s Minister for Armament and War Production Speer had created a sensation when he was recalled to the witness box to give an account of his attempt to assassinate Hitler, at the very end of the war, by introducing poison gas into the vents of the Fuehrer’s bunker in Berlin. This, and the considerable personal risk Speer had taken in sabotaging Hitler’s earlier orders for the total destruction of production facilities in occupied territories and Germany, had been considered as being mitigating circumstances by the Tribunal and explains the comparatively mild sentence he received.

Читать дальше