It worked!

R.W. Cooper, the correspondent of The Times had this to say about our performance: ‘It all worked splendidly, in spite of occasional delays through technical hitches and, in the beginning at least, translations that broke off in mid-air and made little sense. In such cases recourse could always be had to the recording of the original statement as a check to the shorthand record. Considering the limitless scope of the issues involved, technicalities of politics, military terms or the empty phrases of Nazi jargon, every credit is due to the international band of translators under Colonel Leon Dostert, a teacher of French literature in the United States.’

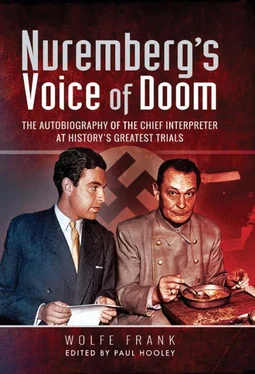

At this point Mr Cooper’s comments become rather complimentary as far as I am concerned and modesty does not prevent me from quoting him further: ‘And by common accord Captain Wolfe Frank, translating from German into English, who came to Nuremberg in British uniform and returned as a civilian, was the ace of them all.’

He did not, of course, listen to the German booth but writes: ‘The translations into German, happily, were especially well done, as could be seen from the readiness with which the accused and their counsels followed the proceedings.’

Certainly, at no time during the entire trial was there a complaint, or even a challenge, directed at the interpreters. This implies an unqualified seal of approval for Dostert’s daring experiment that, so a mathematically gifted observer pointed out, shortened the Nuremberg Trials by at least three years.

31. RETURN TO CIVVY STREET

BEFORE AND JUST AFTER THE BEGINNING OF THE TRIAL we were isolated from anything German, but as time passed by, I established good and sane relations with many Germans and I gradually worked out a way of living a normal life. Old friendships were resurrected, and new ones were made.

I had my contact, through Diels, with his friends who lived outside the town and for some time, my visits to them had to be kept secret.

There was no lack of diversionary activities. The US Army was doing a great deal more to entertain and pamper its men than we, in the British contingent, had ever known. The PX – the shop for the courthouse personnel – was well stocked with the kind of luxurious merchandise I hadn’t seen since before the war. Food rations were generous and even our British Army cook could not ruin them completely. Most of the time I was eating in an American officers’ mess, and the playground for all was the Grand Hotel, opposite the Nuremberg station, which served meals one could buy against ‘scrip’ – a military currency. The hotel boasted the Marble Room, a ballroom for dancing to German bands and a nightly floorshow. The bar was well stocked and Charley, the barman, was a first-class exponent of the art. There was hardly an evening when I did not adjourn to this ‘home away from home’.

I did have a transportation problem. Colonel Turrell, who was in charge of transport, had introduced some absurd rule whereby senior ranks, major and above, were entitled to use staff cars with drivers whilst junior officers, including me, the eternal captain, had to ride in army trucks equipped with uncomfortable seats, and we were restricted to carefully planned communal outings. Such a truck would, for instance, depart from the Grand Hotel for my billet in Zirndorf five minutes after the official closing of the Marble Room, thus precluding any extracurricular activities, such as sex, unless one could stay overnight. This had to be corrected. I needed a car, but there was no way of getting one – officially. Barman Charley came to the rescue. He knew of a small Opel, tucked away in the garage of some widow or other, which could be obtained against some vital food and medical items the old lady needed but couldn’t get on the German economy. Nor could she ever hope to get the car back on the road as she didn’t rate any petrol under strict German rationing, and the car, furthermore, had no papers.

The deal was consummated, and I now owned an Opel Olympia that had no papers or number plates. Fortunately, Major Tom Hedges, the officer in charge of security in the Palace of Justice (who came through with all sorts of other gifts as time went by) produced some beautiful, self-reflecting plates from his garage. They were Swedish. He also introduced me to the sergeant in charge of the American motor pool – and I had fuel.

My undocumented Swedish plates were only challenged once. I was driving along the Autobahn towards Berchtesgaden, when I was flagged-down by an officer who had just overtaken me in a Mercedes. His car, to my horror, had Swedish plates. This could mean trouble. However, as the officer came walking up to me I saw that his uniform was that of the International Red Cross. Things were looking better. Then a flood of words in Swedish descended upon me. This was not so good. ‘Sorry’ I managed to interrupt, ‘but I don’t speak Swedish.’

How come, he wanted to know, was I driving a Swedish car? I concocted a totally insane and improbable story. I had, I told him, bought the car from a member of the British Embassy in Stockholm. My friend had gone back there and was sending me the papers and the car would then be registered with British plates. As this nonsense was pouring out, my tall and distinguished compatriot was beginning to grin. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘I see.’ He introduced himself as Count Bernadotte, Head of the International Red Cross. He wished me good luck and departed with a friendly wave. He was a man who did not wish to make trouble for anyone. No other problem ever arose.

I was now, at last, enjoying complete freedom of movement, limited only by the 01.00 hours curfew for Allied personnel.

I set off for Munich and a visit to see my mother and I arranged for her to move into much better quarters. I had been sending her essential things and I found her looking much better and being pampered by people around her now that she was enjoying the protection of her British officer son.

I paid several visits to Maditta’s home and we soon reached the conclusion that we were no longer right for each other. She had a visitor one evening when I called in to see her on my way to Garmisch for some skiing. I had seen him somewhere before and finally realised he was checking up on me. I started to ask questions, and he gave me all the answers. His name was Joe Warner, and he was with CIC. He had been assigned to investigate me. Somebody had become interested in my extracurricular excursions in my unlawful automobile. Having been found to be ‘clean’ I was left in peace and not a word reached my commanding officer. Joe Warner and I became firm friends and he was instrumental in getting the denunciations against Diels’ hosts cleared up and he was able to protect them until he went back to the US. Joe also fell in love with Maditta, unsuccessfully, I’m afraid, but he cleared the way for her to depart for Canada and marriage long before Germans were able to travel overseas in the normal course of events.

Garmisch was the number one saving grace during my Nuremberg days. We used to travel up and down the mountain by means of a gondola, in which only a few Germans were allowed to ride – if there was any room for them. One day I was standing on the platform of the station, waiting for the gondola to swing in, and idly looking at the crowded German waiting area. There I saw, wedged into the tightly packed crowd, Lieutenant-Colonel Volchkov, alternate Russian member of the International Military Tribunal. Don’t ask me how he had got in there and why. Possibly the German ticket collector had mistaken him for a displaced person. Certainly, nobody could have understood any protestations he or his side might have voiced, because if anyone had realised who he was they would have trembled in fear and bowed him aboard. Naturally, I went into action. I grabbed Hermann, the man in charge with whom I was on good terms, and told him that he had a guest of honour and who he was, and where. We dived in amongst the waiting Germans – ‘There’s a Russian General in there’ shouted Hermann – and the crowd parted like the Red Sea and Hermann ushered the Colonel and his adjutant aboard the gondola.

Читать дальше