However, the Kaltenbrunner sitting opposite me that day was accusing his captors of considerable unkindness. He complained about the glaringly bright light shining into his cell at night, spoiling his sleep, and of the lack of notepaper and pencil on which to write his memoirs, or letters to his ‘beloved wife and family from whom he had been separated for so long and who he was missing terribly’. (He had been captured in the house of his mistress who was now living with an American in Nuremberg and spilling the beans). I was totally dumbfounded when, in fact, he produced tears at that point of his monologue.

As far as a defence counsel was concerned, none of the names before him appealed to him. He wanted, so he explained, to be defended by a colleague from the days of his studies in Vienna, Dr Gustav von Scanzoni. This was a famous name. Scanzoni was an expert on international law who had been forced to leave Germany for political reasons when the Nazis came to power. He was known to be living in Zurich.

I aimed to give Dr Kaltenbrunner the perfect service and picked up the telephone.

Through an excellent performance by the US Signal Corps, Scanzoni was on the line within five minutes. It was against the rules to allow Kaltenbrunner to talk to him, so I conducted the conversation for him. I still vividly remember what was said:

‘This is Captain Frank, British Army, speaking from Nuremberg, Dr von Scanzoni. I have been instructed by the International Military Tribunal to help the future defendants in selecting their defence counsel. May I ask whether you are familiar with the subject of the proposed trial?’

‘ Natuerlich (of course)’ came the answer and the tone of his voice did not seem too friendly. I went on: ‘I am now with Dr Ernst Kaltenbrunner, your former fellow student. He says you will certainly remember him. He wishes me to ask you if you are willing to handle his defence before the Tribunal.’

The lengthy answer was neither complimentary to Kaltenbrunner nor couched in terms as one would expect to hear from a man of such superior intellect. Nor was there any interrupting the outburst. In fact, before I had completed my piece of polite acknowledgement, the famous jurist had hung up on me.

Kaltenbrunner settled on somebody else. Before he was taken away to his cell I said something to him that was certainly a breach of the regulations: ‘Kaltenbrunner, you have provided a most pleasant memory for me – I saw you cry!’

Nothing unusual occurred during my conversations with the other top Nazis when each of them picked their defence counsel from the names on the list.

29. REHEARSALS

AT THIS POINT WE MUST TRIFURCATE MY ACCOUNT because there are three aspects to this chapter in my life which deserve to be related: (a) the interpreting story; (b) the trial and the men involved; and (c) my own life in the middle of it all.

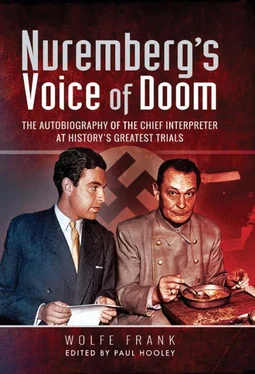

Having been an interpreter at the Nuremberg Trials of the Major War Criminals, Goering et al., is an unfailing conversation piece and as such seems to arouse as much interest as ever.

To have been labelled ‘The Voice of Doom’ in the international press after I announced to the defendants the verdicts – their actual sentences – entitles me to a minor degree of immortality, I suppose.

Towards the end of October 1945, all of Dostert’s bilinguals had arrived, none of whom, including me, had ever interpreted simultaneously. We would all have welcomed the opportunity to practice the art. Could one really, we were wondering, listen to earphones and deliver speech into a microphone clearly, loudly and quickly enough to do the trick? We had to wait for the answer.

The IBM equipment had been duly shipped to Bremerhaven where a truck was to pick it up and deliver it to Nuremberg. However, perhaps predictably, the load went astray and ended up in Genoa, Italy, where some signal officer of the US Army was feeling at quite a loss as to what to do with it. Fortunately, he stumbled across a bill of loading from which he deduced the equipment’s destination. Better still, he had heard about the trials and, knowing they were just about to start, sent a signal to his counterpart in Nuremberg, one Major Evans, whose technicians were waiting to install it all. The major roared off to Genoa and brought back the consignment.

Unfortunately, it was now late in the day: the trial would open on the 20 November 1945; the courtroom was being rebuilt; and when the equipment arrived it was time to install it. The technicians had a spare amplifier, a few microphones and a lot of earphones and they rigged it all up for us to practice in an attic. We had just five days (and nights) to turn ourselves into ‘Simultaneous Interpreters’ under Dostert’s tutelage. Only one of us could practice at any one time since we had no booths, and these practice sessions covered every aspect of our brand new profession. (The institutes of learning nowadays allocate from one to four years for the teaching of the techniques necessary to achieve the required levels of competence). I shared the attic with an interesting collection of court interpreters-to-be.

There was Margo Bortlin, a tall, blonde American who was labelled the ‘Passionate Haystack’ so named partly because of the intricate structure of tresses piled on top of her head and partly because of some indiscreet rumours from the grapevine. Margot became a remarkably competent and accurate interpreter, only slightly handicapped by a voice that was unbelievably twangy and metallic, and a glass-hard American accent. She was as over-awed as the rest of us by the gadgetry before us and the first sentence she ever uttered into a microphone referred to a Nazi law as ‘backfiring’ ( rueckwirkend in German), instead of being retroactive. I believe this was the only mistake Margot made at any time.

There was Tom Brown, Professor of Languages at the University of Florida. He was the most consistently successful poker player at Nuremberg. Tom achieved recognition – and as far as the long-suffering press corps was concerned, total approval – during testimony by a German who was asked if he had attended a high-level Gestapo meeting in Berlin. The German answer to this simple question ran like this: ‘My Lord, it must of course be appreciated that this happened several years ago and I must endeavour to cast my mind back very far,’ (There was no sound from Brown in the English booth) ‘a difficult task, considering the momentous events which were taking place then and afterwards,’ (still total silence from Brown), ‘but I think I can recall that on the day in question I was attending the funeral of my brother-in-arms Schmitt in Munich. It would, therefore, be a safe and reasonable assumption and statement to say that I could not have attended the meeting in Berlin.’ At which point we heard the translation from the English booth ‘No, my Lord!’ – it was greatly appreciated by all concerned.

There was Captain Harry Sperber of the US Army (see Plate 9). German by birth Harry became a successful cartoonist in New York. He had been one of German radio’s most popular sports commentators and, as his speciality was boxing, he had been sent to the USA to cover the Max Schmeling [1] Maximilian Schmeling (1905-2005) was a German former world heavy-weight boxing champion who fought American Joe Louis in New York in 1938 for the world title. Because of their national associations the fight became a worldwide cultural event. Louis won by knocking Schmeling out in the first round – an event that did not please Adolf Hitler or the Nazi Party.

– Joe Louis fight. Whilst in New York, and having done some of the pre-fight broadcasts for German radio, the Nazi Propaganda Ministry discovered Harry was Jewish. Goebbels was informed and had a cable sent to Sperber ordering him to withdraw from the assignment and, incredible as this may sound, to provide a suitable replacement. Sperber’s reply appeared in every newspaper around the world, excluding Germany, and it read: ‘Dr Goebbels. Goetz von Berlichingen. Sperber.’ (Goetz von Berlichingen is the knight in Goethe’s play of the same name who appears at the window of his beleaguered castle and shouts at the enemy: ‘ Leck mich am Arsch ’ – ‘Kiss my Arse’ words which in polite German society one did not use.

Читать дальше