There was a pretty girl from New York, Virginia von Schon, who had grown up in the sheltered atmosphere of a truly God-fearing, Catholic German-American family. She was an extremely literary young lady, with one serious gap in her education, she knew not one ‘bad’ word – not one. A German witness for the defence was on one occasion rendering an enthusiastic account of the ‘holiday-like’ atmosphere in a concentration camp, where, he asserted: ‘They had schools, a university, library, a gymnasium, went for walks in the country and even had a…’ at which point Virginia had dried up. ‘What did the witness say, they even had?’ enquired Lord Justice Lawrence. This went back to the witness, via the German booth, and he reiterated his enthusiastic account of Himmler’s, ‘home away from home’. The third time round, the monitor, a much decorated American infantry captain, who was permanently seated outside our booths to cope with the unexpected, reached over and seized Virginia’s microphone, ‘A whorehouse, my Lord, a whorehouse,’ he explained. ‘And the Tribunal will look into the question of amending the record,’ said his Lordship in closing the incident.

One other major correction off the record became necessary when another prim young lady interpreter, lacking profanity of language, did not know what to do with the German word ‘ Scheisskerle ’ which means ‘Dirty Shits’ (plural). She searched her memory frantically for a dirty word and could only think of one – ‘Fucking Fellows’ she said, in impeccable King’s English. The record was amended.

There was also a phenomenon among us, Prince George Vassiltchikov an American-born direct descendant of the late Tsar of Russia. I will always remember George for three outstanding qualities: (a) he had three unbelievably beautiful sisters; (b) he became the best Russian-English Interpreter at the United Nations; and (c) he suffered from an extremely bad stammer. This, for an interpreter, would appear to be an insurmountable handicap. But George’s stammer disappeared the instant he faced a live microphone. It was an eerie thing to be listening to his linguistic stumblings one second and to hear them replaced by the smoothest possible delivery an instant later.

Back at the Palace of Justice our five days of rehearsals in the attic were soon over and the gadgets were whisked away to be installed in the courtroom. The opening of the Trial was only eleven days away. We kept reading to each other, practicing voice control, delivery, syntax, grammar, vocabulary, reading documents, hearing lectures by attorneys, and helping

Dostert set up the teams. He had wisely decided and decreed that a team could not work longer than an hour and a half at any one stretch. He had made up three teams; A, B and C. Team A would work the morning session, starting at 09.30 hours and continue until the morning recess at 11.00 hours. During that time, Team B would be sitting in an adjoining room – number 606, I remember – listening to the proceedings in the courtroom, thus ensuring complete continuity of terminology and awareness of what had been happening. Team C, on that day would be resting. On the following day, Team B would start, and C, as listeners, would pick up the vocabulary. Team A would be free, and so the rotation would continue. Each team had twelve interpreters, three per language, except for the Russians who ran their own show and never joined us in room 606, or anywhere else, for that matter.

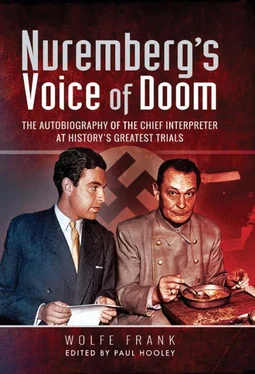

This arrangement had the additional advantage of ensuring a three-day weekend for two out of three teams, one being off duty on Friday, the other on Monday, the third on the following weekend. Later, after we had overcome our initial stage fright and almost unbearable nervous tension, the working hours arranged by Dostert were the maximum of what we could do. [1] 2 At times ‘Dostert broke his shift system to take advantage of Frank’s outstanding qualities as an interpreter’ (Ann and John Tusa, The Nuremberg Trial ). It seems also that on occasions, and because he was the best, the BBC requested that the Tribunal use Frank for the more important broadcasts and in his memoirs Dostert makes it clear that Frank was the only interpreter who could be used in both the English and the German booths.

30. DEBUT PERFORMANCE

THE DEGREE OF ACCURACY REQUIRED FROM US, the total concentration on the proceedings, even when one was not actually interpreting, and the tension emanating from the courtroom during the ten-month mental battle fought over the lives of the twenty-one defendants, put a tremendous strain on the nervous and mental stamina of the interpreters.

None of this was obvious to us when 20 November dawned after, for most of us, a sleepless night. I was to give my debut in the German booth and had been reading, and re-reading, the opening statements to be read by Justice Jackson and Sir Hartley Shawcross. [1] Sir Hartley Shawcross KC, MP, HM Attorney-General was the Chief British Prosecutor at the IMT.

They were to be preceded by an opening statement by the President of the Tribunal, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence and the indictment would be read in open court. Translations of these documents had reached us a day earlier, so we had been able to prepare ourselves to the extent that we knew these texts. What terrified us most was the business of listening and talking simultaneously, and, of course, the prospect of impromptu statements that were certain to occur. I had met Karl Anders, a commentator of the BBC’s German service a couple of days before and he had casually mentioned, ‘About fifty million people will be listening to your German interpretation of the opening of the trial’ – a prospect that did not exactly tranquilize my nerves. (That figure grew to several hundred million when I interpreted Goering’s testimony four months later, but by then I was an old hand at the game).

Starting on that morning of 20 November 1945 we, the newly created ‘Multi-Lingual Simultaneous Court Interpreters’ set out on the seemingly endless task of voicing six million words – predominantly in English and German – that were spoken during the ten-month trial. On that first morning, seated in the German booth, my mouth was painfully dry and my hands were shaking. Never before, or since, have I known such nervous pressure or such a fear of the unexpected. It was comparable to those feelings I had had (in a previous life) at the start of those downhill ski races in which I had competed where one’s fear is of having a bad tumble in full view of the spectators.

On opening day we had a full house, of course. The Press gallery was packed. The Defence and Prosecution teams were all in place. The lights were glaringly bright for the photographers (no film cameras). The glassed-in booths for radio commentators, above the room, were filled to capacity. Then the klieg lights [2] Klieg lights are powerful lights used in filming and photography.

were turned off and the photographers withdrew. The Marshall of the court announced the entry of the Tribunal – and suddenly I was interpreting for the first time. I don’t remember doing the few impromptu comments by the President, but I do remember having started reading the German translation of his opening remarks. I told myself to put more expression into my reading, to speak more clearly, to work on my voice control and to stop shaking. I managed all of that fairly quickly, but the jitters took weeks to disappear and the nervous tension never completely left me.

We were, after all, involved in the writing of history and our contribution was of the greatest importance. None of the judges understood German and everything said in that courtroom to them by the defendants and witnesses passed through the ears, brains and mouths of we interpreters.

Читать дальше